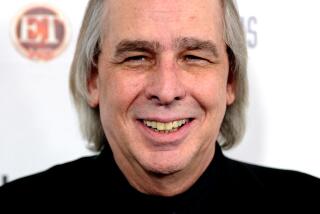

Carroll Pratt dies at 89; Emmy-winning sound engineer

- Share via

Carroll Pratt, an Emmy-winning sound engineer who also worked with the inventor of the laugh track and spent decades adding laughter and other effects to a variety of shows, has died. He was 89.

Pratt died of natural causes Thursday at Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital in Santa Rosa, north of San Francisco, said his son, Scott Ouchida-Pratt.

Pratt was working as a re-recording mixer at MGM in the early 1950s when he was approached by Charles Rolland Douglass, who invented the Laff Box, which was basically a series of audiotape loops. Douglass asked Pratt to work for him when business got too big to handle himself.

They were joined by Pratt’s brother, John, as the use of laugh tracks took off in TV comedies and other shows, first to fill in sounds and later to provide laughter in shows without an audience or augment the real audience’s reaction.

The Pratts eventually started their own business, trying to make their contributions hard to spot amid industry pressure to provide bigger laughs.

“One thing I feel strongly about is that if you go to a movie or watch a TV show where the musical composer has done his job, you never realize the music is playing. It’s all lending itself to the effect that the art form should have,” Pratt said in the 2004 book “Creating Television” by Robert Kubey. “If a laugh track is well laid in, I feel that the best compliment is someone coming to me and saying that the show got through without a laugh track.”

Said Ed Greene, a veteran audio mixer who knew Pratt for more than 30 years: “Carroll used his skill to pick his audience, then he had the sensitivity to know how to use it. It’s not easy. He’s supposed to fit in so it sounds real natural.”

Carroll Holmes Pratt was born April 19, 1921, in Hollywood. His father, also named Carroll, was a sound engineer in radio and film.

The family moved to Australia when Pratt’s father took a leave from MGM to work on the 1931 film “Showgirl’s Luck,” then returned to Southern California.

He graduated from Santa Monica High School and followed his father to MGM in 1939. Pratt attended Santa Monica College, but enlisted in the Army Air Forces in 1942.

During World War II, his B-24 bomber was shot down over Austria with Pratt and the other crew members parachuting to land. Pratt was held prisoner for nearly two years before escaping from a German camp in 1945.

After the war, Pratt returned to MGM and worked his way up the ranks. Then came television and his role with what he called “the audience reaction machine.”

In an interview with the Archive of American Television, Pratt called Douglass “a wonderful man” and said he never regretted working with him.

Douglass’ machine ultimately featured hundreds of human sounds that could be used by a sound operator. Pratt said Douglass’ business took off in part because producers who were doing filmed shows without audiences saw the advantage of having a laugh track. Douglass died in 2003.

The machine Pratt and his brother used when they started their own company had “endless cassettes that loop around in a regular mounting, the same as a household audiocassette player,” he said in “Creating Television.” They built a library of sounds taping a variety of shows in different locations.

One tape contained shorter laughs and “there are about 30 to 35 different chuckles before we get around to the start again. We mix them to avoid the feeling of repetition. Hopefully you’ll never hear the same laugh in a show twice.”

Pratt said he learned his craft “by being the audience to the shows I was ‘laughing,’ ” he told the Globe and Mail newspaper in 1996. “Ninety-five percent of the time you know when the joke is going to hit. There’s no brilliance to it, just habit, repetition.”

Karen Herman, director of the Archive of American Television, said Pratt “watched the pulse of America in comedy, going from the 1950s to the ‘90s.”

And what about when producers and writers wanted bigger and more canned laughs?

“The major complaint was we were laughing at things that weren’t funny,” he told the Associated Press in 1996. “Then we got letters saying we don’t need some guy pushing a button to tell us when to laugh.”

Greene said Pratt “knew how to handle producers, directors and writers who tried to overuse [the laugh track]. He was a master politician at dealing with people.”

Pratt shared six prime-time Emmy Awards for sound mixing, including for “The Grammy Awards” in 1989, “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” in 1987 and “Motown Returns to the Apollo” in 1985.

In addition to his son, Pratt is survived by his wife, Carole; a daughter, Micky Krugman; four grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren. Two other marriages ended in divorce. John Pratt died earlier this year.

Services will be held at 7:30 p.m. Thursday at the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences’ Leonard H. Goldenson Theatre and at 5 p.m. Saturday at the Apple Hall at the Mendocino County Fairgrounds in Boonville, Calif. Pratt had retired in nearby Philo, Calif.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.