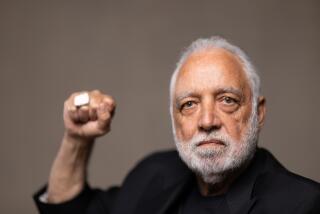

Dan Walker dies at 92; ex-Illinois governor worked to regain reputation

- Share via

In Illinois, Dan Walker was a star: a campaigner for civil rights, a reform-minded governor, a possible presidential candidate, a populist Democrat unafraid to stand up to the political machine of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley.

But by the time he returned to San Diego, where he had grown up, it was all different. Walker was broke, disgraced and divorced; his fall from power and prominence had been as sharp and surprising as his meteoric rise.

From 1973 to 1977, he was the governor of Illinois, having caught the public’s imagination with his Kennedy-like charisma and grass-roots campaigning style. But a reelection loss and then a conviction in 1987 for bank fraud in a savings-and-loan scandal led to 18 months in prison.

Soon after his release in 1989, he moved to San Diego in hopes of making a living and restoring his good name.

The historians will now have to ponder whether he found the redemption that he sought so vigorously. Walker, 92, died of heart failure Wednesday at his Chula Vista home, according to his family.

After his return to San Diego, Walker worked for several years as an aide to Catholic Msgr. Joseph Carroll at the St. Vincent de Paul Village program that provides housing, meals and job training for the homeless.

The man who had once dreamed of living in the White House lived in a one-bedroom apartment; once his car of choice was a Rolls-Royce; now he drove a borrowed subcompact. When he flew back to Chicago, he had to borrow money from his children for the airfare.

“Yes, I am destitute,” he told The Times in 1990. “But I do want to earn a place in the real world again. I’ve got to prove I can do it.”

Walker had found job prospects lean for a convicted felon. After doing volunteer work at a homeless center in Virginia Beach, Va., as part of his probation, he thought the St. Vincent de Paul program would be a good fit.

Noting his extensive management experience, Carroll hired him at $250 a week to help establish a charitable giving program to supplement funding of the homeless program. Any skepticism melted away when he saw Walker’s work ethic.

“He was a sinner but he was also a saint,” Carroll said last week. “He wanted to help the community, to earn respect.”

Pictures in Walker’s tiny office at St. Vincent showed him standing with Presidents Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford, the king of Sweden and the emperor of Japan, and delivering a State of the State address as Illinois governor. “He had some bravado, which you have to have to become a governor,” Carroll said.

But the man who once commanded thousands of employees now “did all his own research,” Carroll said. “He always felt he should be doing that which is right.”

After St. Vincent, Walker worked as a clerk in a bookstore and a paralegal for a law firm. He helped a friend open a sandwich shop.

Walker also wrote books, including a 2007 memoir, “The Maverick and the Machine: Governor Dan Walker Tells His Story,” published by Southern Illinois University Press.

A reviewer for the Chicago Tribune noted that, “The tragedy of Dan Walker, Illinois governor from 1973 to 1977, is painful to witness, even as Walker tells it at age 84, many years after he became a distant memory in Illinois.”

Daniel Walker was born Aug. 6, 1922, in Washington, D.C. The family later moved to the San Diego area, where his father was stationed as a chief petty officer in the Navy.

After his 1940 graduation from San Diego High School, Walker joined the Navy and as an officer served in the latter stages of World War II. He was recalled during the Korean War.

After law school he joined Chicago-based Montgomery Ward & Co., where he became general counsel. He was campaign chairman for the 1970 Senate bid of Adlai Stevenson III.

Walker gained national prominence with his work on a commission investigating the violence between demonstrators and police outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Known widely as the Walker Report, it described the violence as a “police riot,” a phrase that earned the author the enmity of Daley.

As an upstart candidate for governor, Walker defeated a Republican incumbent in 1972. Derided as a campaign gimmick by opponents, Walker’s strategy of walking the state from the border with Wisconsin to the border with Kentucky caught the public’s imagination; he spent 116 days walking and talking to voters, often staying in farmhouses.

Walker was immediately discussed as a presidential contender. But his hopes for a second term as governor were dashed when he lost to a Daley-backed candidate in the 1976 Democratic primary.

After leaving political office, Walker started a company that provided quick oil changes for automobiles, later bought by Jiffy Lube, and became president of a savings and loan corporation. Federal prosecutors said he fraudulently obtained $1.4 million in loans to keep his business afloat and support a lavish lifestyle. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to seven years in prison, but won early release in 1989.

“I’ve faced the fact that I brought it all on myself,” he told The Times in 1990. “I do believe I’ve served my time, paid my price, felt my shame. It still hurts, though. It hurts bad.”

He is survived by his third wife, Lily Stewart, and seven children from his first marriage: Kathleen, Julie, Roberta, Margaret, Daniel Jr., Charles and William.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.