Edmund S. Morgan dies at 97; scholar on early America

- Share via

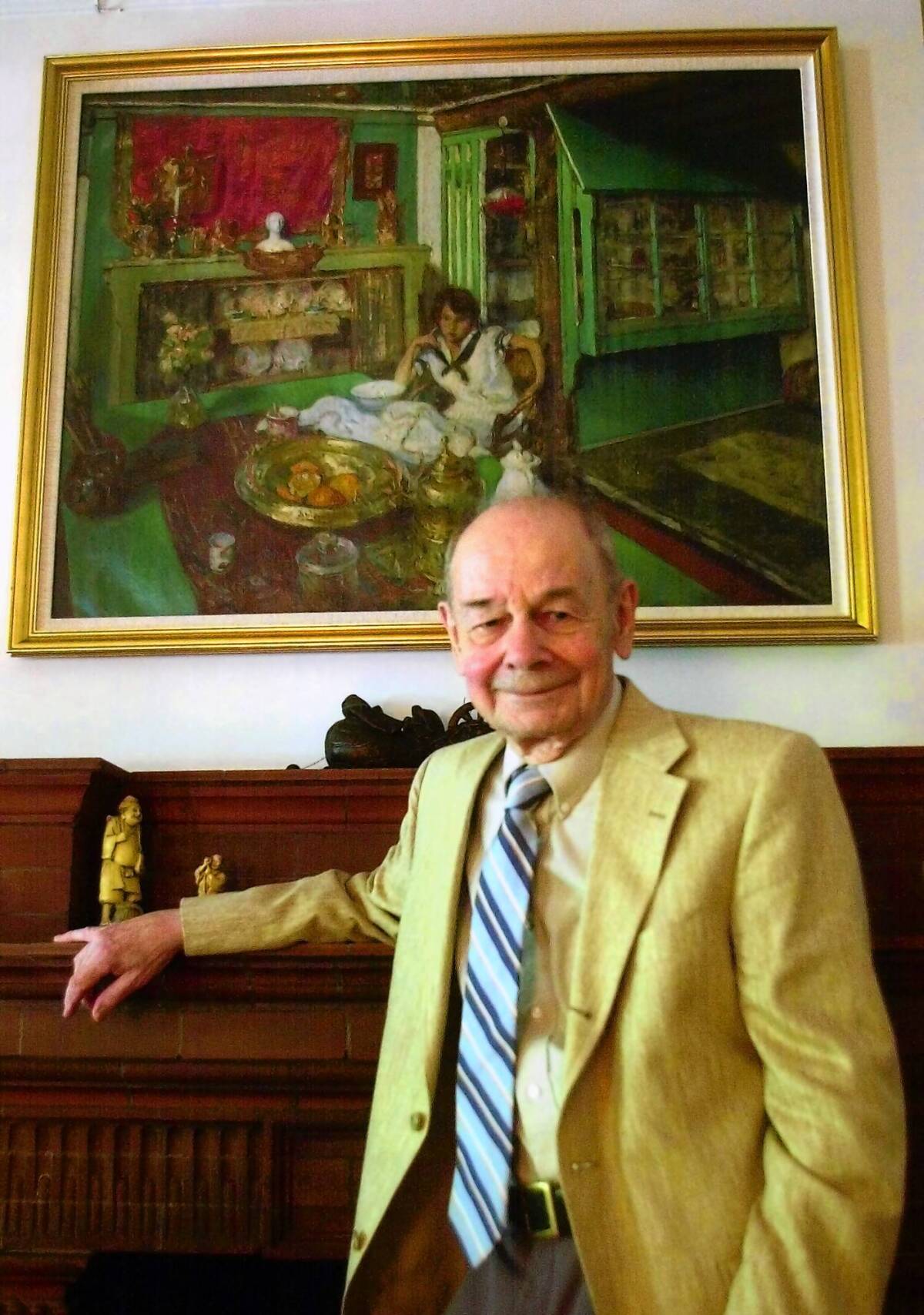

Edmund S. Morgan, a leading scholar of the Colonial era who helped reinvigorate the reputations of the founding fathers, probed the country’s racial and religious origins and, in his 80s, wrote a bestselling biography of Benjamin Franklin, has died in Connecticut. He was 97.

Morgan died Monday at Yale-New Haven Hospital, where he was being treated for pneumonia, said his wife, Marie.

A professor emeritus at Yale University, he was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books and author of more than a dozen books, including “Birth of the Republic,” “The Puritan Dilemma” and “Inventing the People,” winner in 1989 of the Bancroft Prize. His other awards included a National Medal of the Humanities in 2000 and an honorary citation from Pulitzer Prize officials in 2006 for his “creative and deeply influential body of work.”

Morgan shared Franklin’s birthday, Jan. 17, and impish spirit. The bald, round-faced historian had a prankster’s smile; a soft, sweet laugh; and a willingness to poke fun at his own prestige, joking that history books bored him and that his favorite students were the ones who disagreed with him.

For decades, Morgan and Harvard professor Bernard Bailyn were cited as leaders of early American studies. Joseph Ellis, who studied under Morgan at Yale, dedicated his Pulitzer Prize-winning “Founding Brothers” to his former teacher. Gordon Wood, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Radicalism of the American Revolution,” cited Morgan for often being ahead of his time.

“When he was first writing [in the 1940s] the dominant thinking among historians was that ideas didn’t matter, that the founders only cared about the rich and that they didn’t mean what they were saying about freedom and government,” Wood said in 2002. “But Morgan started with the assumption that their ideas were to be taken seriously. He was really bucking the tide.”

Morgan wrote several books and essays about the country’s founders, especially Franklin and George Washington, praising them not just as men of action but of inaction. He cited the “genius” of Washington in declining to seize power after the surrender of the British and found the seemingly sloppy Franklin a far more effective diplomat overseas than the ever-prepared John Adams.

An informed and accessible prose stylist, Morgan liked to imagine his readers as “ignorant geniuses”; the public knew him best for “Benjamin Franklin,” published in 2002, when Morgan was 86. It was a short, lively summation. Based solely on the historian’s reading of Franklin’s volumes of papers, which Morgan helped organize, the book sold more than 100,000 copies and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award.

But Morgan never imagined that the founders were perfect or that the country’s early history was unscarred by racism. In his acclaimed “American Slavery, American Freedom,” winner in 1976 of the Francis Parkman Prize, he documented how demands for greater freedom in Colonial Virginia were influenced by the rise of slavery, which gave whites a heightened sense of entitlement. In “Inventing the People,” Morgan stated that politicians often used democratic language as a cover for maintaining power.

Morgan did not plan to major in history much less specialize in the Colonial era. Born in Minneapolis in 1916 and raised in New Haven and the Boston area, he dreamed of owning a ranch as a boy and preferred English to history when he entered Harvard University.

But after studying at Harvard under Colonial historian Perry Miller, Morgan became fascinated by the Puritans and wrote about them in his first book, “The Puritan Family,” published in 1944. “Miller was an atheist, and so was I, but we both had this tremendous regard for the intellectual grounding of their theology,” Morgan said in 2002.

Known for his thorough research, Morgan preferred the founders’ own words to the books written about them.

“I don’t read many biographies,” he said in 2002, acknowledging that he hadn’t gotten around to David McCullough’s million-selling book on Adams. “I can spend all day reading Washington’s papers.… I can do that all day long. But if I pick up the kind of book that I write, I go to sleep.”

Morgan was married twice. He and his first wife, Helen M. Morgan, co-authored “The Stamp Act Crisis,” published in 1953. In recent years, he collaborated on reviews and essays with his second wife, Marie Morgan.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.