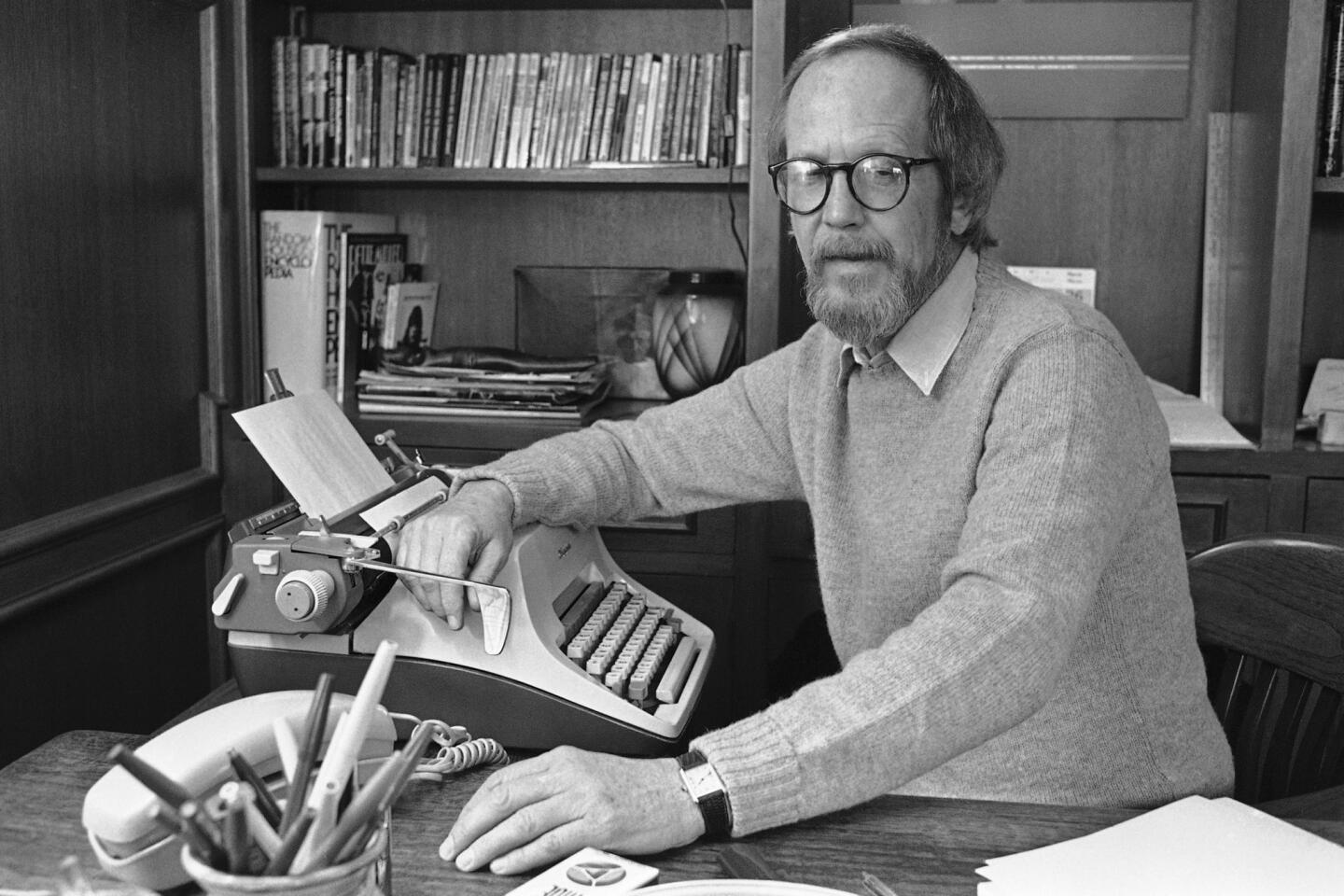

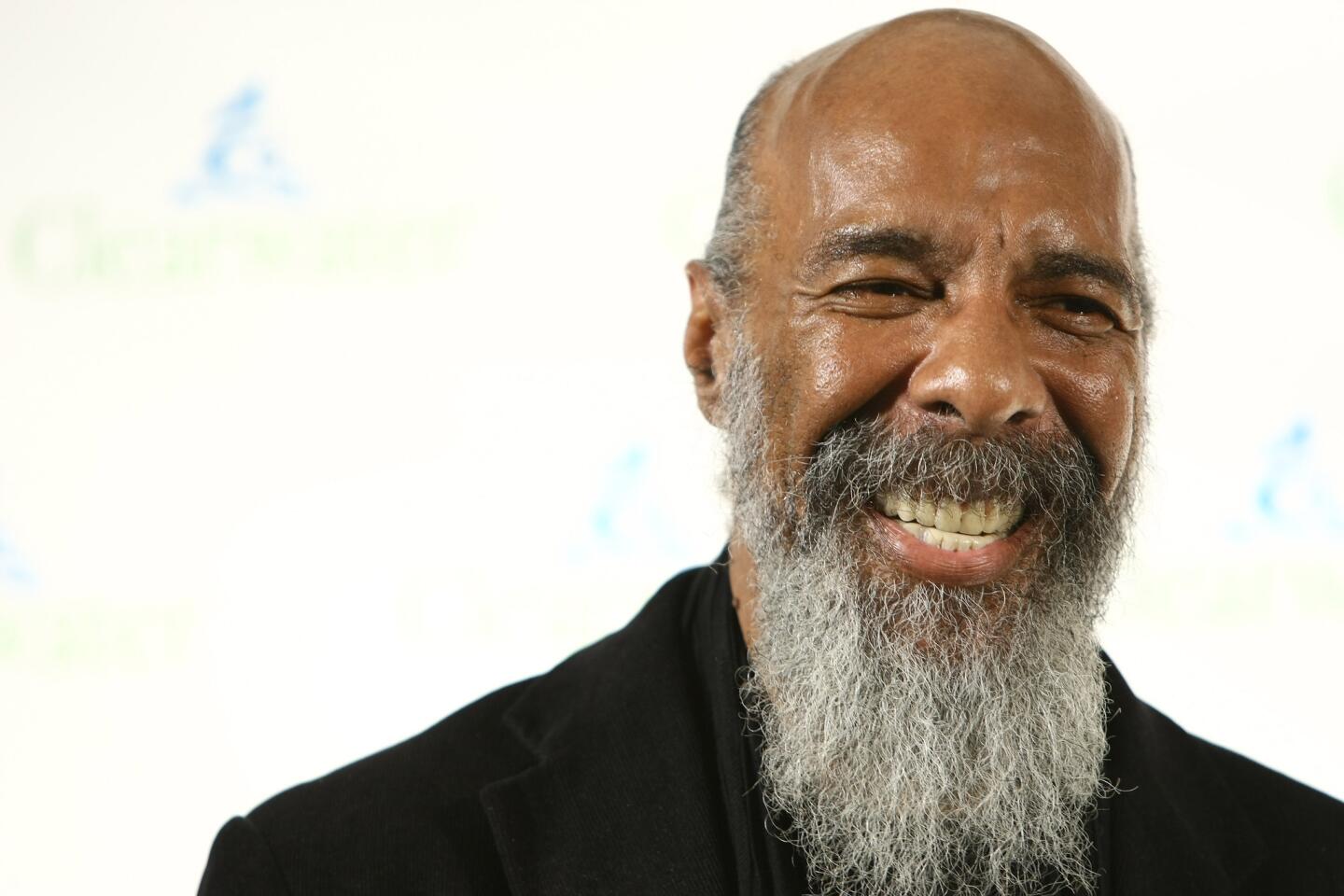

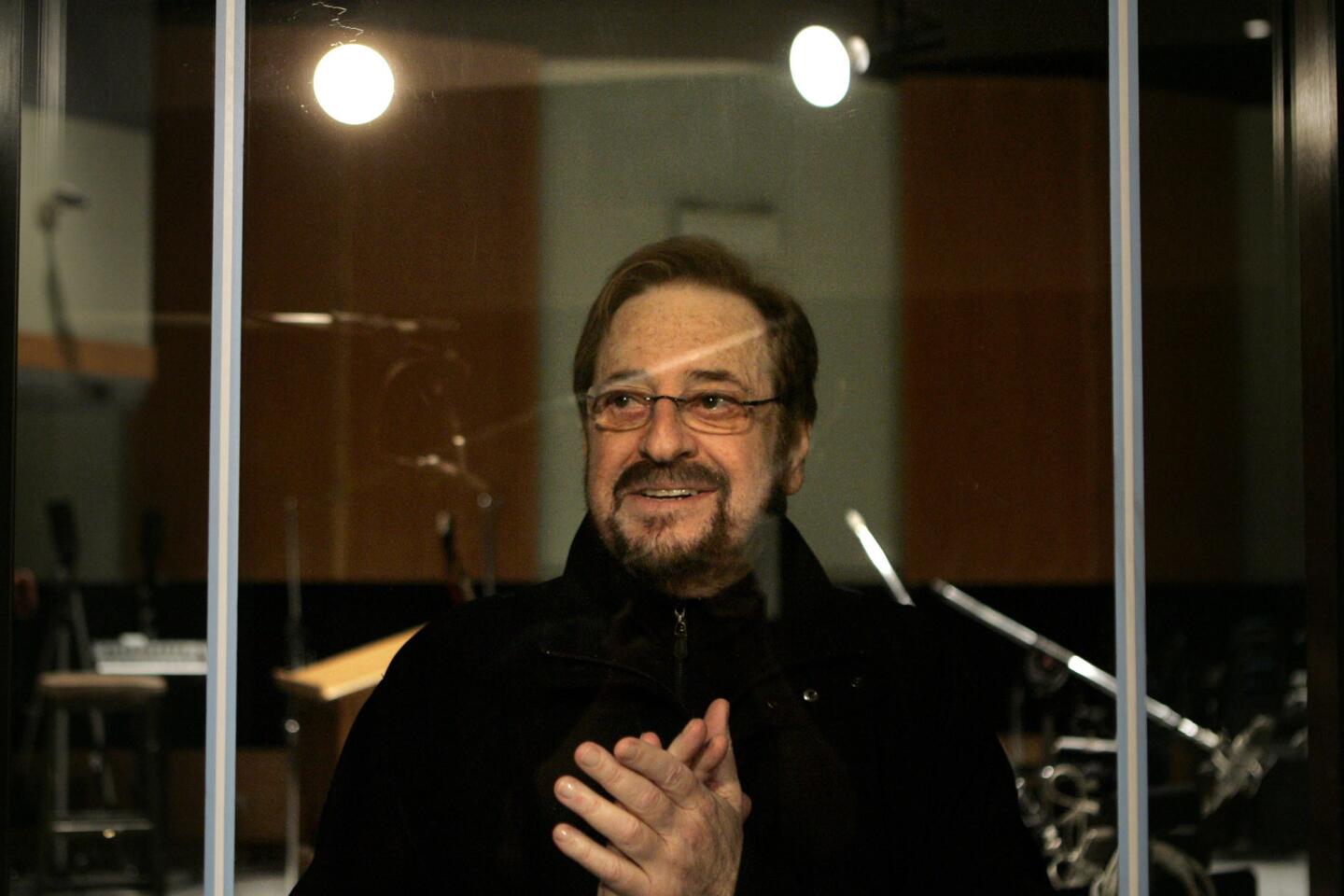

Geza Vermes dies at 88; scholar wrote about Dead Sea Scrolls

- Share via

Geza Vermes was a graduate student in Belgium in the late 1940s when he was captivated by news sweeping the globe about a remarkable discovery in the desert east of Jerusalem. He quickly switched gears, penning his doctoral thesis on the Dead Sea Scrolls, the ancient manuscript fragments that would become a focus of his life’s work.

FOR THE RECORD:

The headline on an earlier version of this article said Vermes had died at the age of 89. He was 88. Also in the earlier version, the first name of Mark Goodacre, an associate professor of religion at Duke University, was incorrectly reported as Martin.

The timing of the discovery, Vermes would later say, was among many “providential accidents” of a life that carried him from Hungary to England and from Judaism to Catholicism and back again. He became one of the first scholars to translate the scrolls into English and later wrote engaging, seminal works about the Jewish origins of Jesus.

Vermes, whose compelling personal history, like his writings, bridged Jewish and Christian worlds, died May 8 in Oxford, England, said David Ariel, president of the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, an independent center of Oxford University where Vermes spent much of his career. He was 88. The cause was not disclosed.

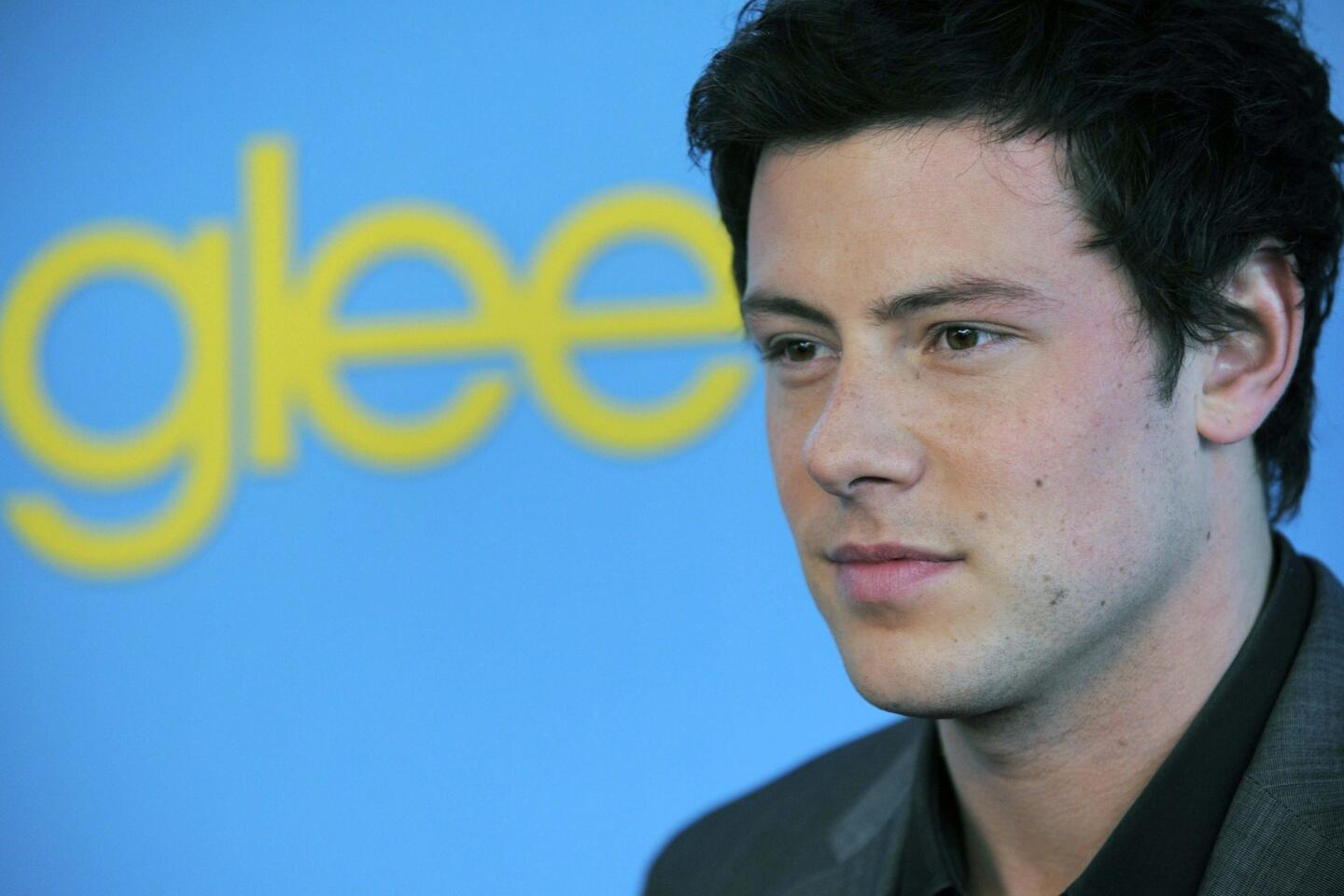

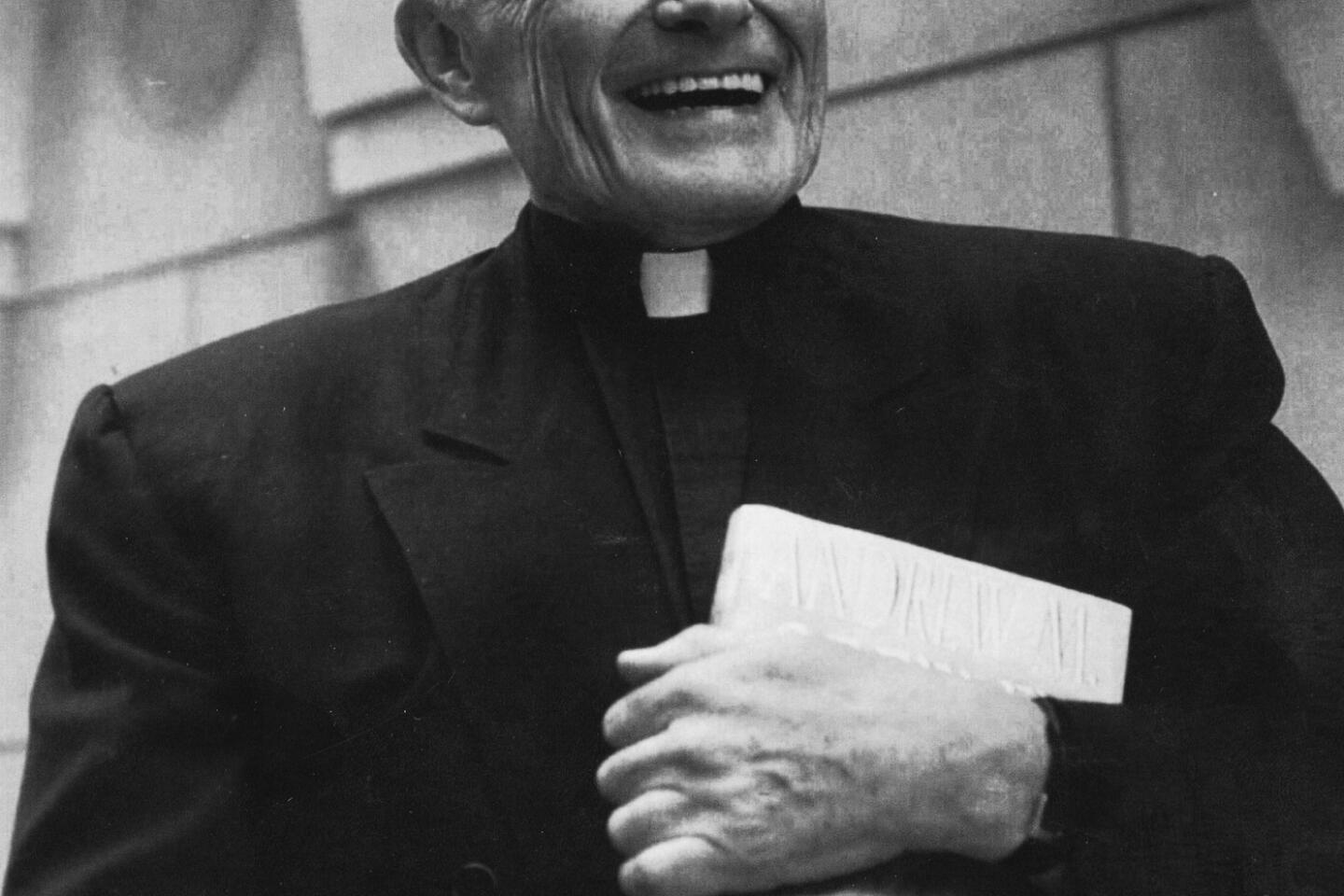

A Hungarian-born Jew who converted to Catholicism as a child and, for a time, became a priest, Vermes became known for his skillful translations of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which were first discovered in 1947 and contain the earliest known versions of the Hebrew Bible.

A strong advocate of open access to the scrolls, he was praised for his dedication to revising and expanding his books as additional manuscripts were discovered and became available.

“Because he constantly updated his translations when new scrolls came out, he had a tremendous impact on the accessibility of the scrolls to scholars and the public,” Lawrence Schiffman, vice provost of undergraduate education at Yeshiva University in New York and an expert on the manuscripts, said this week. “His translations were considered the most influential and most reliable.”

Vermes pushed for more open access to the scrolls at a time when a small group of scholars held tight control over the material, keeping most others out. The lack of access sparked decades of sometimes turbulent jockeying by scholars eager to study the manuscripts, which date from about the time of Jesus and offer insights into Jewish thought and practice.

“He was both one of the pioneering scholars, disseminating understanding of what the Dead Sea Scrolls contained, and a real crusader for more open access,” Ariel said.

But Vermes, who had left the priesthood and Catholicism by the late 1950s, also used his understanding of Judaism of the period to write a pioneering series of books that reclaimed the historical Jesus as a Jewish holy man and teacher. The first, “Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels,” was published in 1973.

The work was a leap forward for historical Jesus studies, a field that was beginning to come to terms with historic elements of anti-Semitism, said Mark Goodacre, associate professor of religion at Duke University.

“Vermes’ book just blew all that out of the water,” Goodacre said this week. “He essentially showed that it was unacceptable to think about Jesus as if he were not a Jew. And because Vermes was knowledgeable about both Jewish and Christian sources, he saw Jesus as someone moving within the context of his time, making for a more rounded view.”

Vermes, who helped popularize Biblical studies, appearing frequently on BBC documentaries about religion, also wrote about key moments in Jesus’ life, including his birth, trial and resurrection. His final book, “Christian Beginnings: From Nazareth to Nicaea, AD 30-325,” was published in 2012.

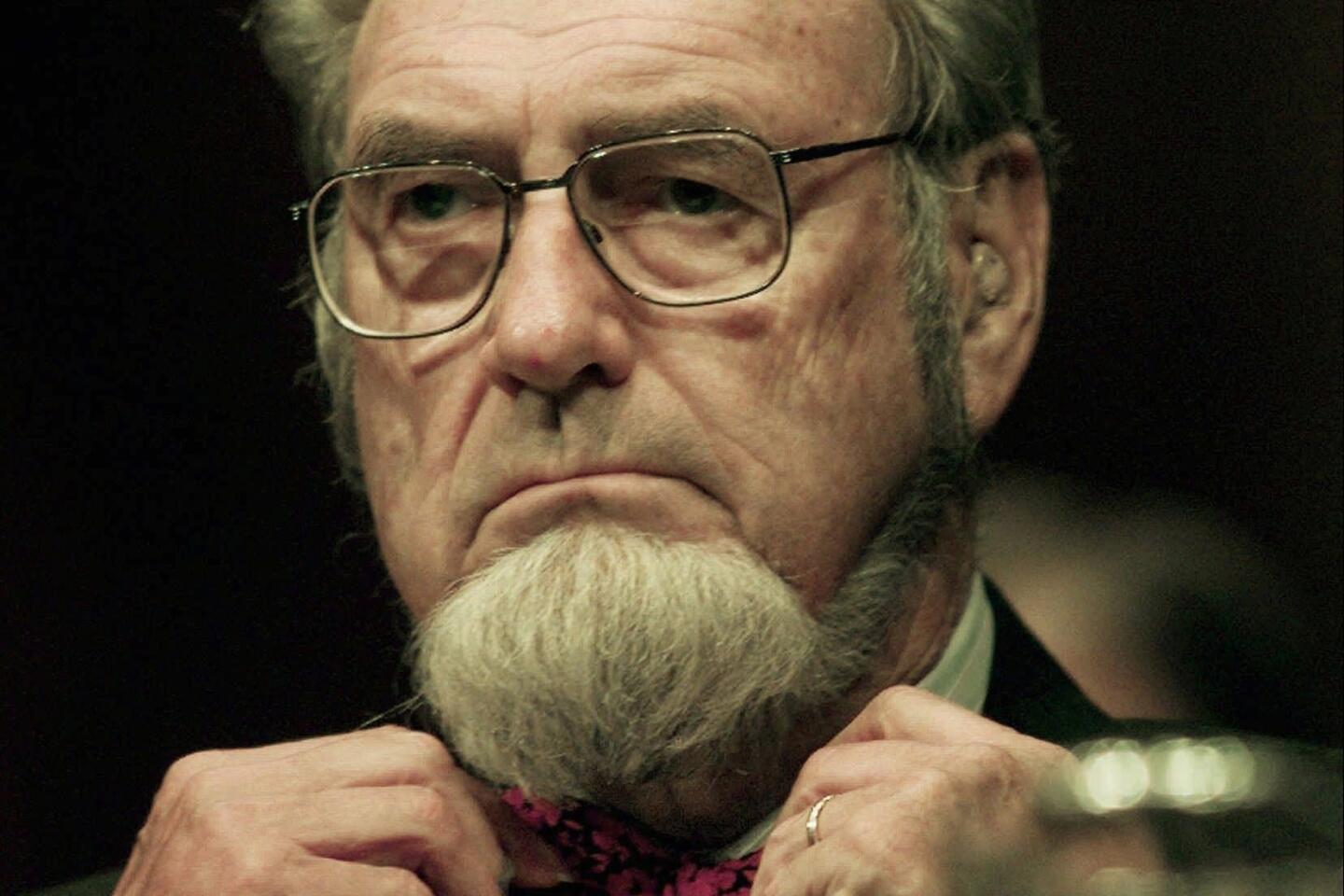

In a book review published in the Guardian newspaper, Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury, praised Vermes as “the unchallenged doyen of scholarship in the English-speaking world on the Jewish literature of the age of Jesus, especially the Dead Sea Scrolls.”

But Williams said the book, while “beautiful and magisterial,” left unanswered fundamental questions about Christian doctrine, including how Jesus came to be seen as an object of worship.

Vermes came to his understanding of Christianity and Judaism through his own experience.

Born June 22, 1924, in Mako, Hungary, Vermes and his parents, Erno, a journalist, and Terezia, a teacher, were non-practicing Jews who were baptized as Catholics in 1931, when he was 6. He later said his parents had hoped to protect the family from rising anti-Semitism in Europe, but both were eventually arrested and sent to concentration camps in Poland, where they died.

In his late teens, Vermes had chosen to study for the priesthood in Budapest. The decision almost certainly saved his life as the priests sheltered him, keeping him from deportation. After the war, he joined a Belgian religious order and was sent to the Catholic University of Louvain, where he earned a doctorate in theology in 1953 and began his work on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

He left the priesthood and the Catholic Church in 1957, and later returned to his Jewish roots, eventually joining a synagogue. The same year, he moved to England and took a job as lecturer in divinity at the University of Newcastle. In 1965, he was appointed a lecturer in Oriental studies at Oxford University, rising to become a professor of Jewish studies before his retirement in 1991.

Vermes’ first wife, Pamela, died in 1993. He is survived by his wife, Margaret.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.