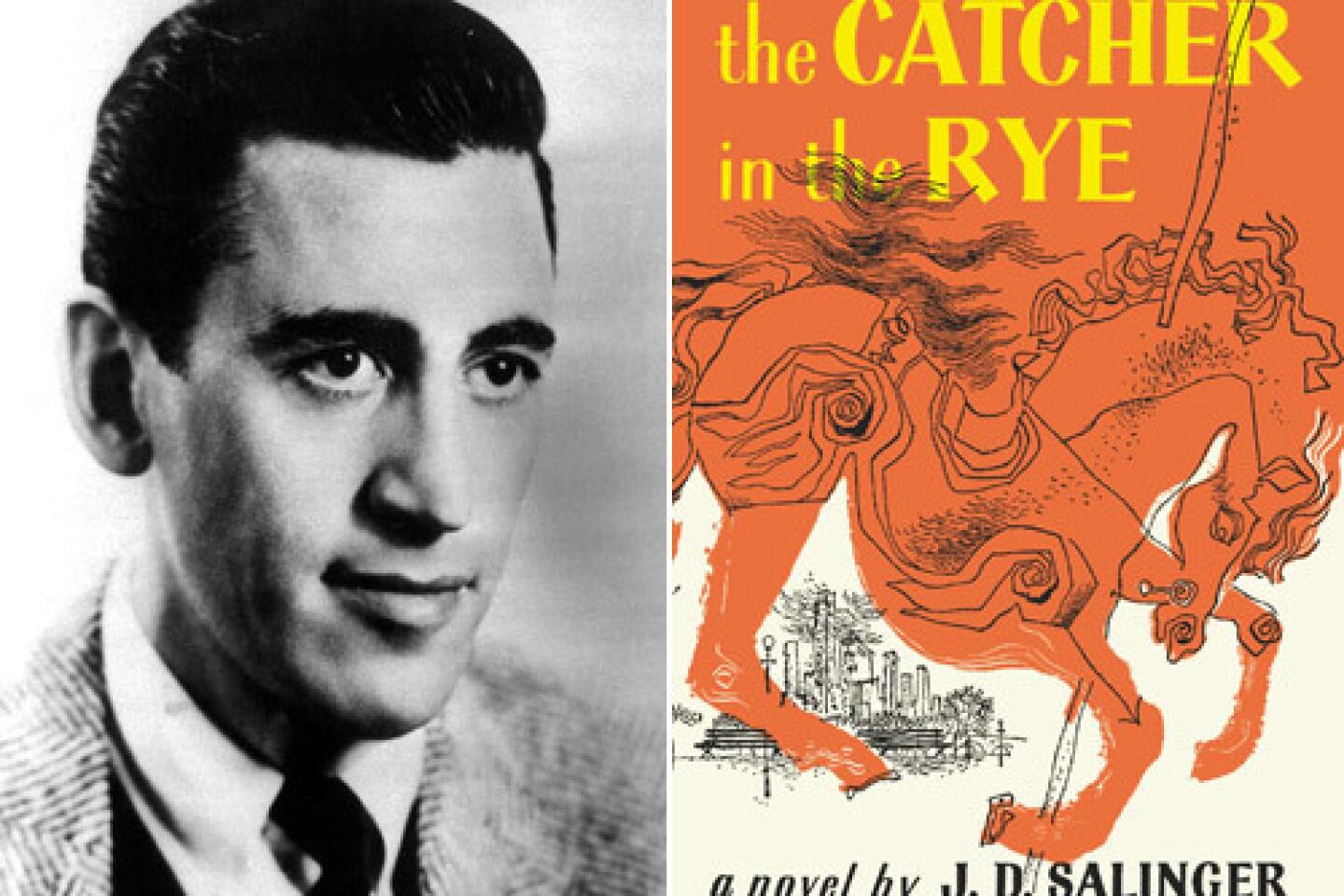

James J. Kilpatrick dies at 89; newspaper columnist and arbiter of language

- Share via

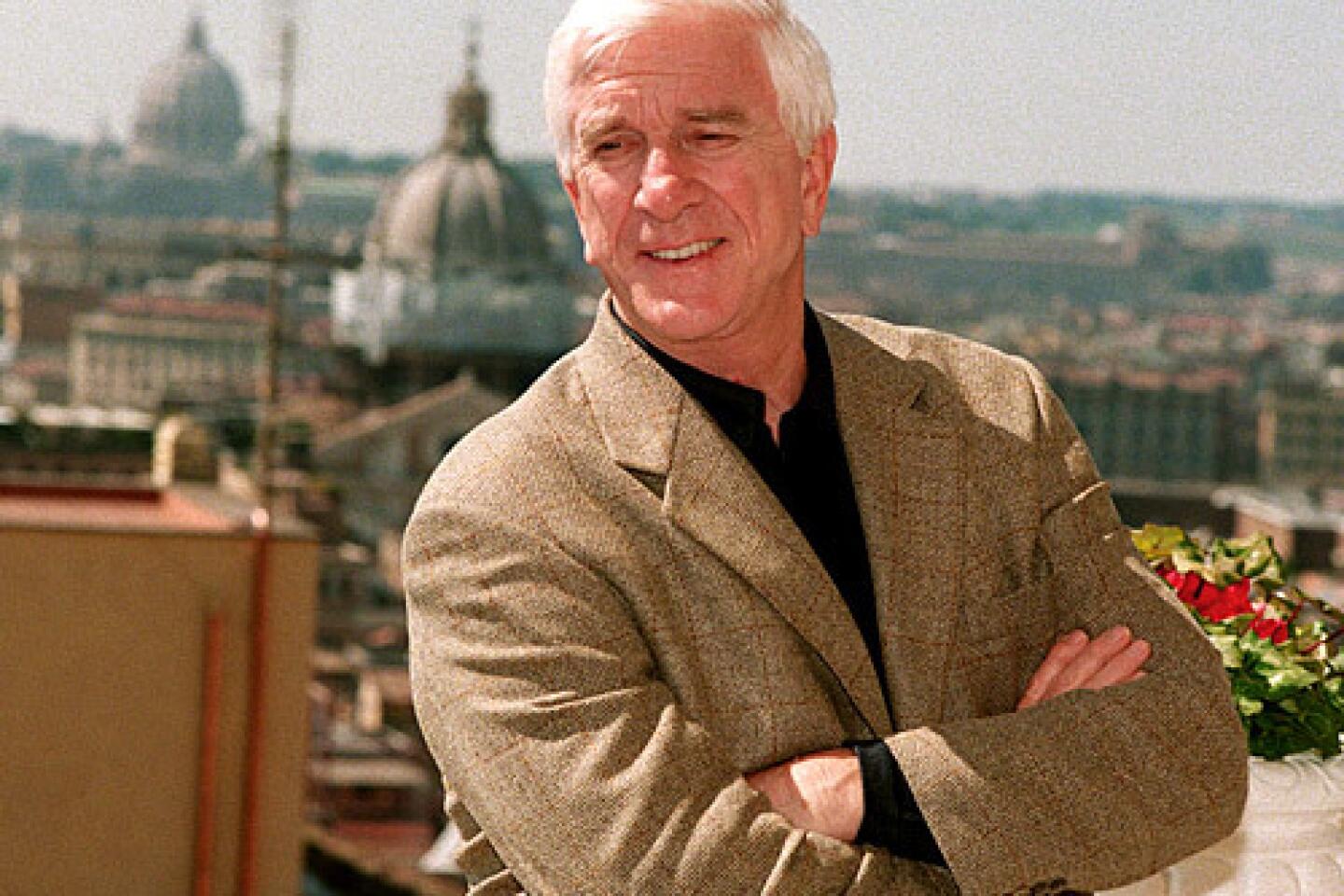

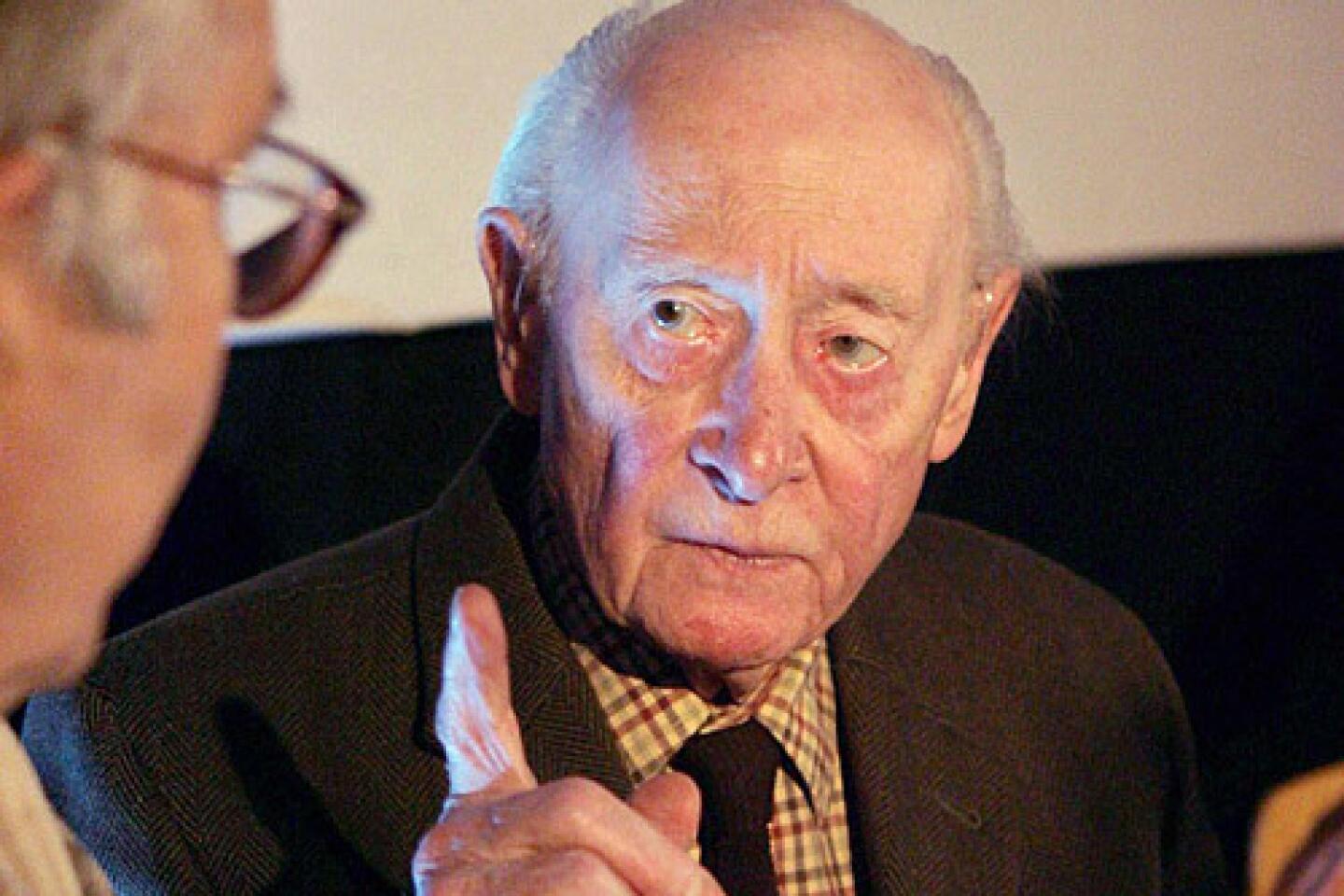

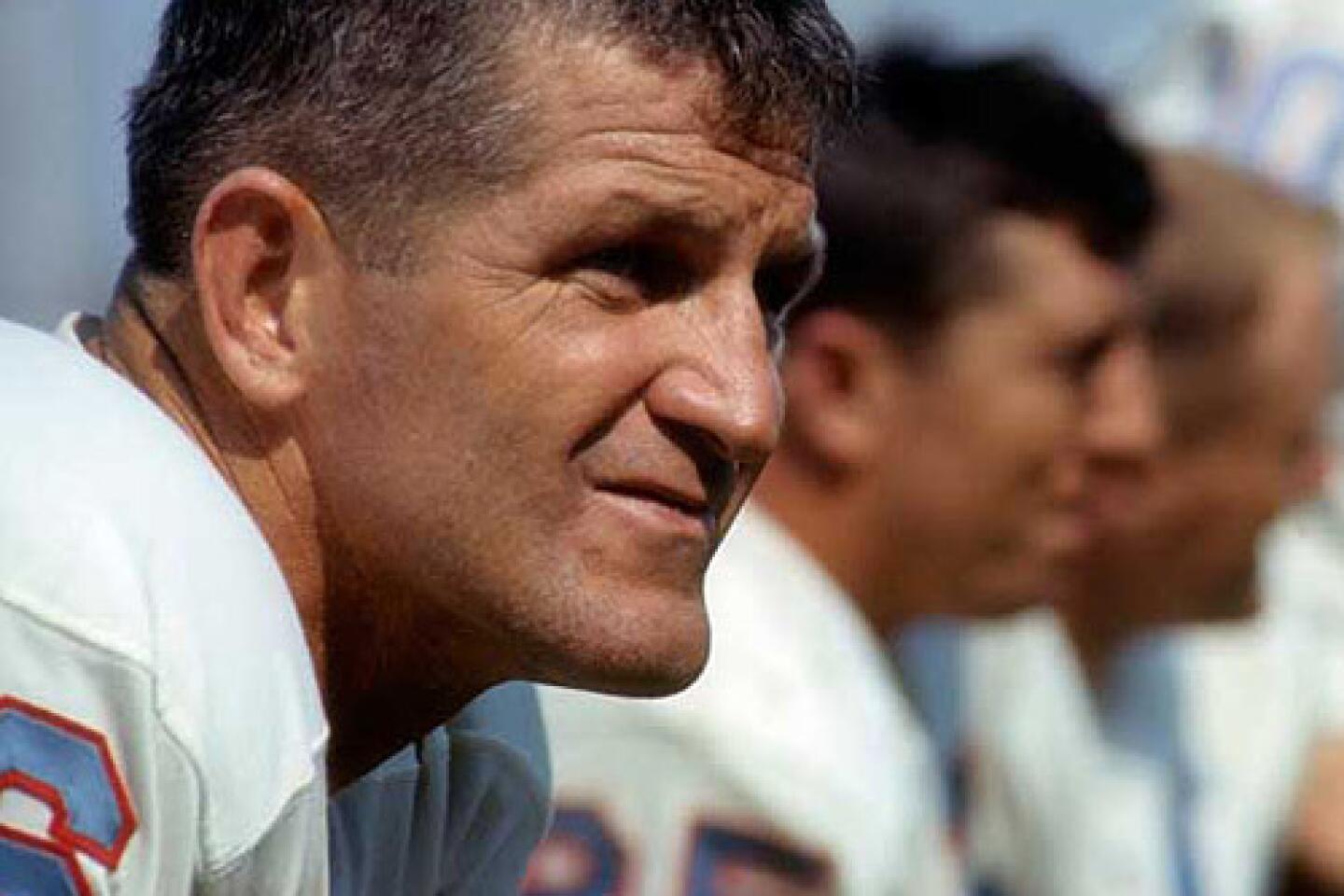

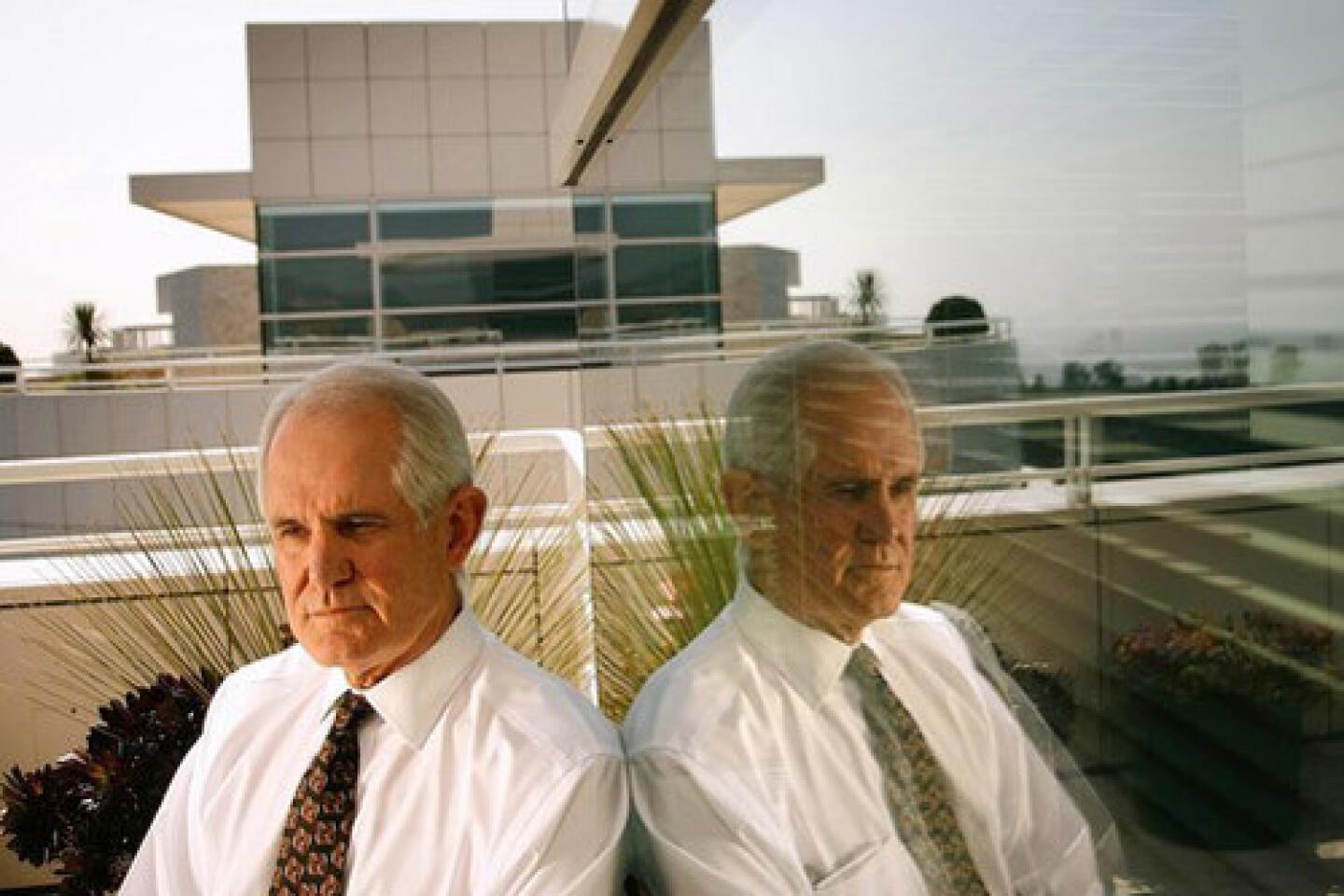

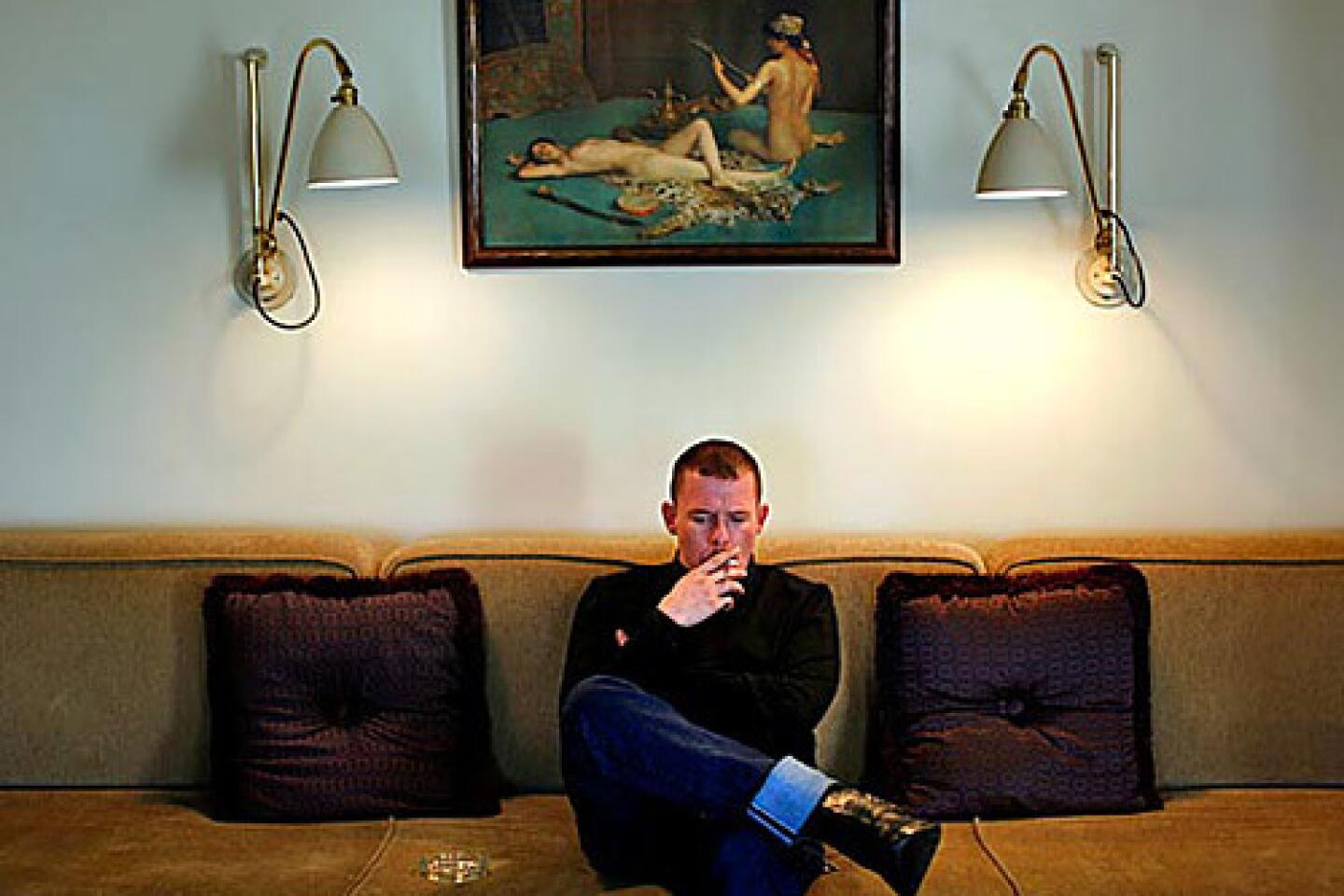

James J. Kilpatrick, a nationally syndicated columnist whose strongly conservative viewpoints on politics, law and language appeared in hundreds of newspapers over the last five decades and made him a popular, even parodied, television pundit, died Sunday at a Washington, D.C., hospital. He was 89.

The cause was congestive heart failure, said his son, Kevin.

Kilpatrick, who once described himself as “10 miles to the right of Ivan the Terrible,” was the editor of a Richmond, Va., newspaper in the 1950s. His anti-desegregation crusades gave him national prominence, eventually leading to a thrice-weekly syndicated political column called “A Conservative View.” He later apologized for his stance on race matters, saying that his views had changed with the times.

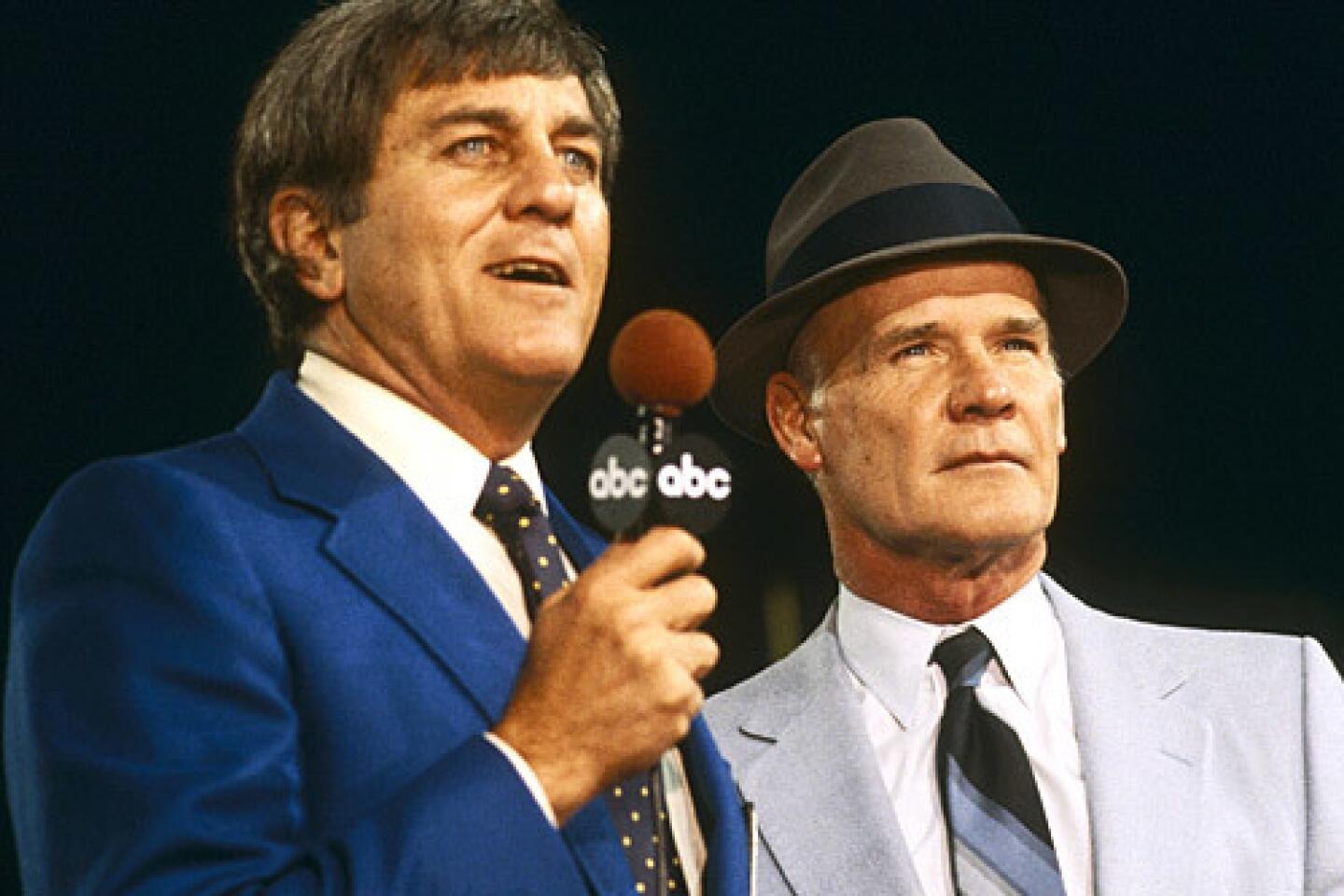

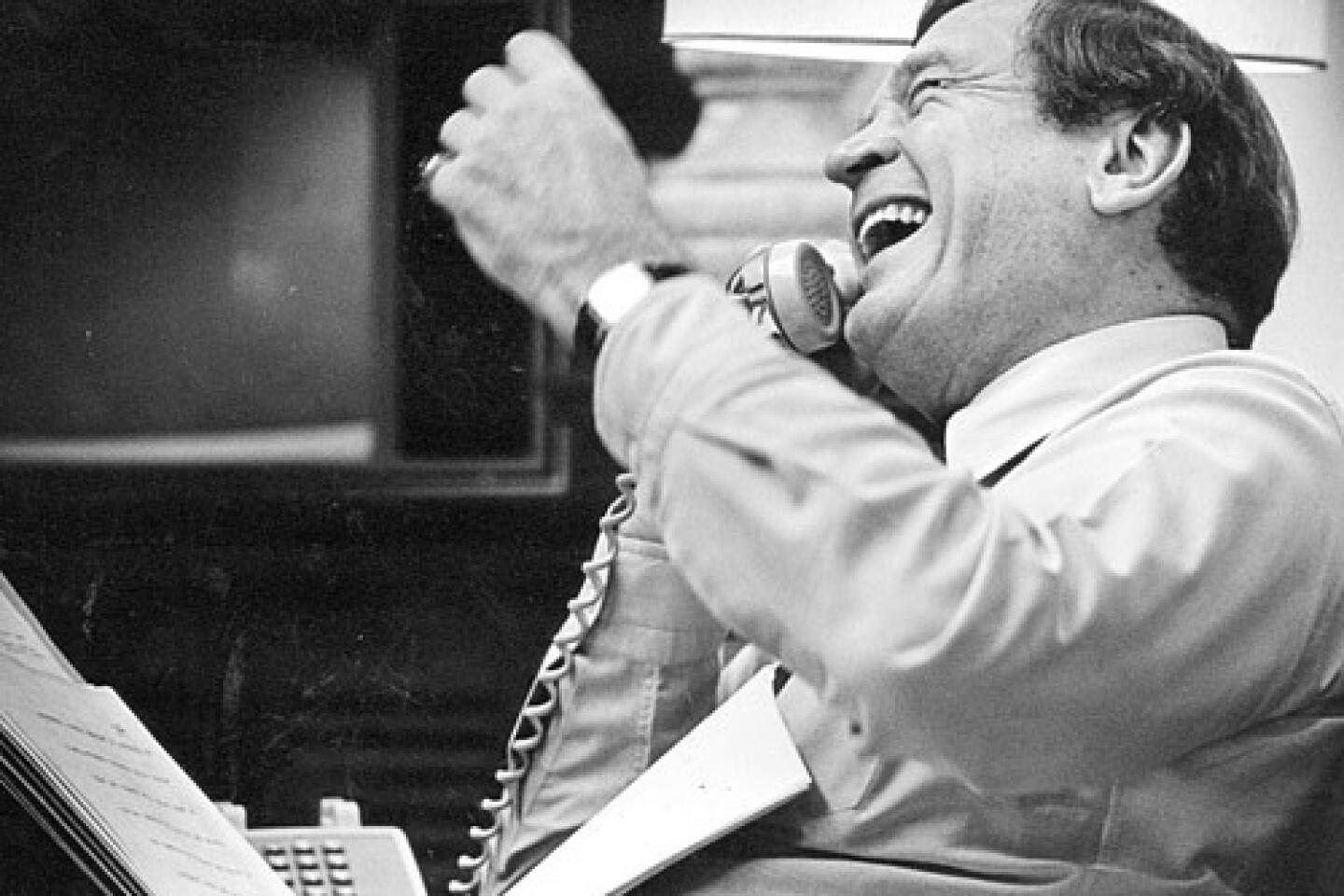

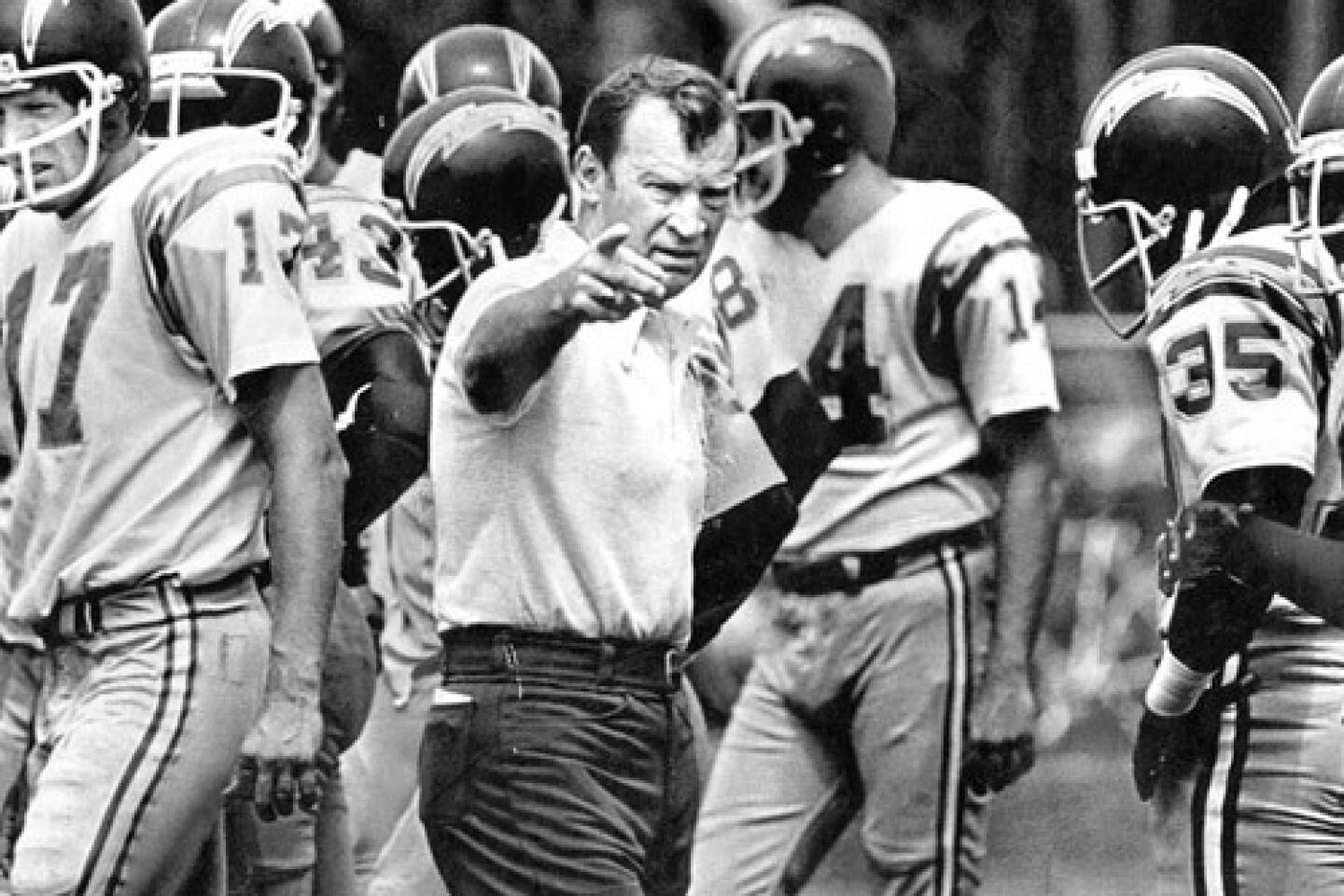

In the 1970s he broadened his audience as a regular on the “Point-Counterpoint” segment of the CBS news show “ 60 Minutes.” His feisty exchanges with liberal sparring partner Shana Alexander inspired a running spoof on the late-night TV show “Saturday Night Live,” with Jane Curtin as Alexander and Dan Aykroyd as Kilpatrick, whose put-downs — particularly Aykroyd’s “Jane, you ignorant slut” — became cultural catchphrases.

Kilpatrick also wrote more than a dozen books, including “The Writer’s Art” (1984), about his love of language and his umbrage at its frequent abuse. His last newspaper column, which appeared in early 2009, concerned the common misuses of the word “only,” a pet peeve that he wrote about every year for 30 years.

Described by political commentator and columnist George Will as “a Jeffersonian, Virginia, small-government, free-market, classic conservative,” Kilpatrick once defined a conservative as one who says “no” more than “yes.”

“If you think of the body politic as a machine, the liberals’ habit is to accelerate,” he told an interviewer some years ago. “The conservatives’ function is to apply the brakes.”

He extolled the merits of a free marketplace, praised self-reliance and hard work, and was tough on crime. When President Nixon deployed the FBI to ferret out troublemakers on the nation’s college campuses in 1970, for instance, he backed the action in unwavering terms: “I think oppression is needed. The more oppression the better. It is high time we cut down on the bums that are blowing up the campuses, as Mr. Nixon described them.”

A few years later, however, the stridency gave way to a more considered questioning of the president during the Watergate scandal. “Just what is a conservative’s view of burglary?” Kilpatrick asked.

One of the most popular columns he ever wrote concerned two skunks who had moved into his home in the Blue Ridge Mountains near Scrabble, Va. He named them Lord Macaulay and Rosebud and explained in elegant prose the quandary of how to get rid of them without killing them. According to his son, he received hundreds of letters from readers offering solutions.

Kilpatrick was born in Oklahoma City on Nov. 1, 1920. The son of a lumber dealer, he was a precocious child who learned to read at 4. In 1937, the year he graduated from high school, his father lost his business, forcing Kilpatrick to support himself through journalism school at the University of Missouri.

He earned his degree in 1941 and went to work as a cub reporter for the Richmond News Leader. A graceful writer with bulldog determination, he worked his way up to investigative reporter, catching the eye of editor Douglas Southall Freeman, who began to groom Kilpatrick as his successor. Kilpatrick became chief editorial writer in 1949 and editor in 1951.

The young editor spearheaded some notable crusades. In the early 1950s, he successfully campaigned to win a pardon for a black man who had been wrongfully convicted of murder. In 1959, incensed about a Richmond pedestrian who was fined for climbing over a car whose driver was blocking a busy intersection, he created the Beadle Bumble Fund, a name inspired by a character in Charles Dickens’ “Oliver Twist.” The purpose of the fund, he wrote, “is to deflate an occasional overblown bureaucrat, to unstuff a few stuffed shirts and to promote the repeal of foolish and needless laws.”

During this period he also became an outspoken opponent of desegregation. He editorialized against the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education, which declared school segregation unconstitutional. The centerpiece of Kilpatrick’s opposition was a 19th century doctrine called “interposition,” which said that states had the right to override a federal mandate that encroached on their sovereign authority. Bolstered by Kilpatrick’s editorials, several Southern states used the interposition argument to pass laws favorable to segregation. Kilpatrick also wrote a book, “The Sovereign States” (1957), to drum up support for the doctrine outside the South, but it failed to gain traction.

Kilpatrick became well-known nationally, particularly after he participated in debates with prominent civil rights leaders, including one with the Rev. Martin Luther King in 1960. He became a contributing editor to William F. Buckley’s conservative journal, National Review, which led in 1964 to his debut as a syndicated columnist with the Newsday Syndicate. In 1965 he switched to the Washington Star Syndicate, which later became the Universal Press Syndicate. His column appeared in more than 400 papers, including The Times from 1964 to1986.

As a syndicated columnist, he began to moderate his view on race. Although some critics expressed cynicism about his transformation, he said it was sincere. “I was brought up a white boy in Oklahoma City in the 1920s and 1930s,” he told Time magazine in 1970. “I accepted segregation as a way of life. But I’ve come a long way. Very few of us, I suspect, would like to have our passions and profundities at age 28 thrust in our faces at 50.”

His first wife, sculptor Marie Pietri, died in 1997. In addition to his son Kevin, he is survived by his wife, Marianne Means, a former Washington columnist for Hearst Newspapers whom he married in 1998; two other sons from his first marriage, Sean and Christopher; seven grandchildren; and 11 great-grandchildren.

elaine.woo@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.