Mike Campbell dies at 78; white Zimbabwean challenged seizure of lands

- Share via

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — Mike Campbell, the white Zimbabwean farmer who won a landmark case in southern Africa’s highest court challenging the seizure of his farm by President Robert Mugabe’s government, died Wednesday. He was 78.

Campbell, whose family said he died of complications from a savage beating by Mugabe loyalists in 2008, called himself a white African.

“We’re not British or Scottish or anything. We’re African,” he said stoutly in a 2007 interviews with The Times.

But he died homeless in the Zimbabwean capital, Harare, after his farm was seized and his house burned down by thugs from the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front.

That wasn’t all he lost. The 2008 beating cost him his health. Afterward, he found he couldn’t solve easy sums, like calculating how much fertilizer to put on a mango tree. His family said he never recovered.

Campbell was famous for his stubbornness and his refusal to compromise with the Mugabe government, which began seizing white farms in 2000. The agriculture-based economy collapsed as farm production plummeted; Mugabe, who came to power as a black liberation hero, had handed out farms to judges, generals, family members, top ruling party officials and others with little interest in farming the land.

After holding out for years against threats to seize his citrus and mango farm, Mt. Carmel, Campbell and his wife, Angela, were driven from their home in 2009, and the family’s ancient pet horse, Ginger, who lived in the garden, ran away into the bush. Months later, the house was burned to the ground.

At the time, Campbell clung to hope he might get the land back. But asked about rebuilding the place, the tough old farmer fought tears.

“I don’t know, quite honestly,” he said at the time. “I’ll have to look at it. I just don’t know.”

It wasn’t to be.

“He knew he was going to die yesterday,” his son-in-law, Ben Freeth, said in a phone interview. “He woke up in the morning and said, ‘I’m going to die today,’ and by 2:15 in the afternoon he was dead.”

Campbell is survived by his wife and his three children, Bruce, Cathy and Laura.

He was a feisty, gruff fellow who did not suffer fools gladly — including the ZANU-PF politicians arriving at his door to beg for donations. He’d send them away with contempt.

Campbell kept his vulnerable side well hidden, lest his enemies see a weak spot.

“He stood for justice, for all of us,” Freeth said. “For me, he was the most tenacious and courageous man I have ever had the privilege to know.”

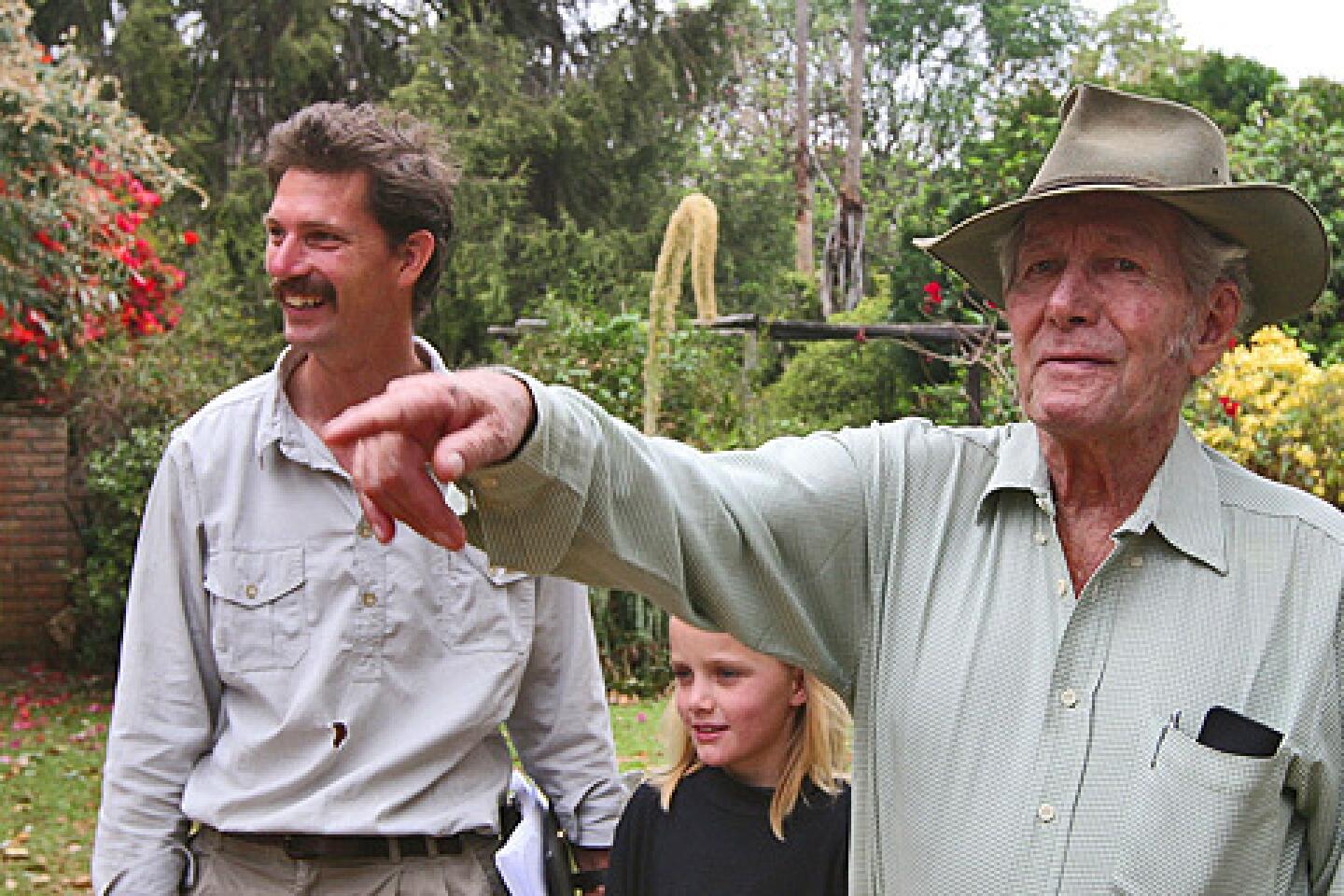

Campbell’s life story was told in the film “Mugabe and the White African,” inspired by a series of articles on Campbell in The Times.

He was born on a farm in Klerksdorp, South Africa, in 1932 and went straight into the army after leaving school. After fighting in what was then Rhodesia’s bush war against the black independence fighters, Campbell bought his land in 1975 and turned it into a game farm and safari lodge. But the game was poached and the lodge burned down. So he changed course and became one of the country’s most successful mango and citrus producers.

Faced with a constant threat of eviction, he refused to kowtow to the ruling party. His survival tactic: Keep on going.

“You’ve got to keep investing in the farm. The moment you stop, they’ll take it away from you,” he said in 2007. “Make no mistake — a very large part of what has been going on is, the person who is on the land owns it. The moment you move off, you’re finished.”

Campbell challenged Mugabe’s land seizures in the region’s highest court, the Southern African Development Community Tribunal.

The tribunal found that the seizure of farms from white farmers without compensation was illegal and racist. Mugabe thumbed his nose at the ruling, and his government was twice found in contempt of the tribunal.

As Campbell lay dying Wednesday, a Christian friend arrived to say goodbye. She asked if he had forgiven the people who had taken everything from him.

A cloud crossed his face. But in the end, his answer was yes.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.