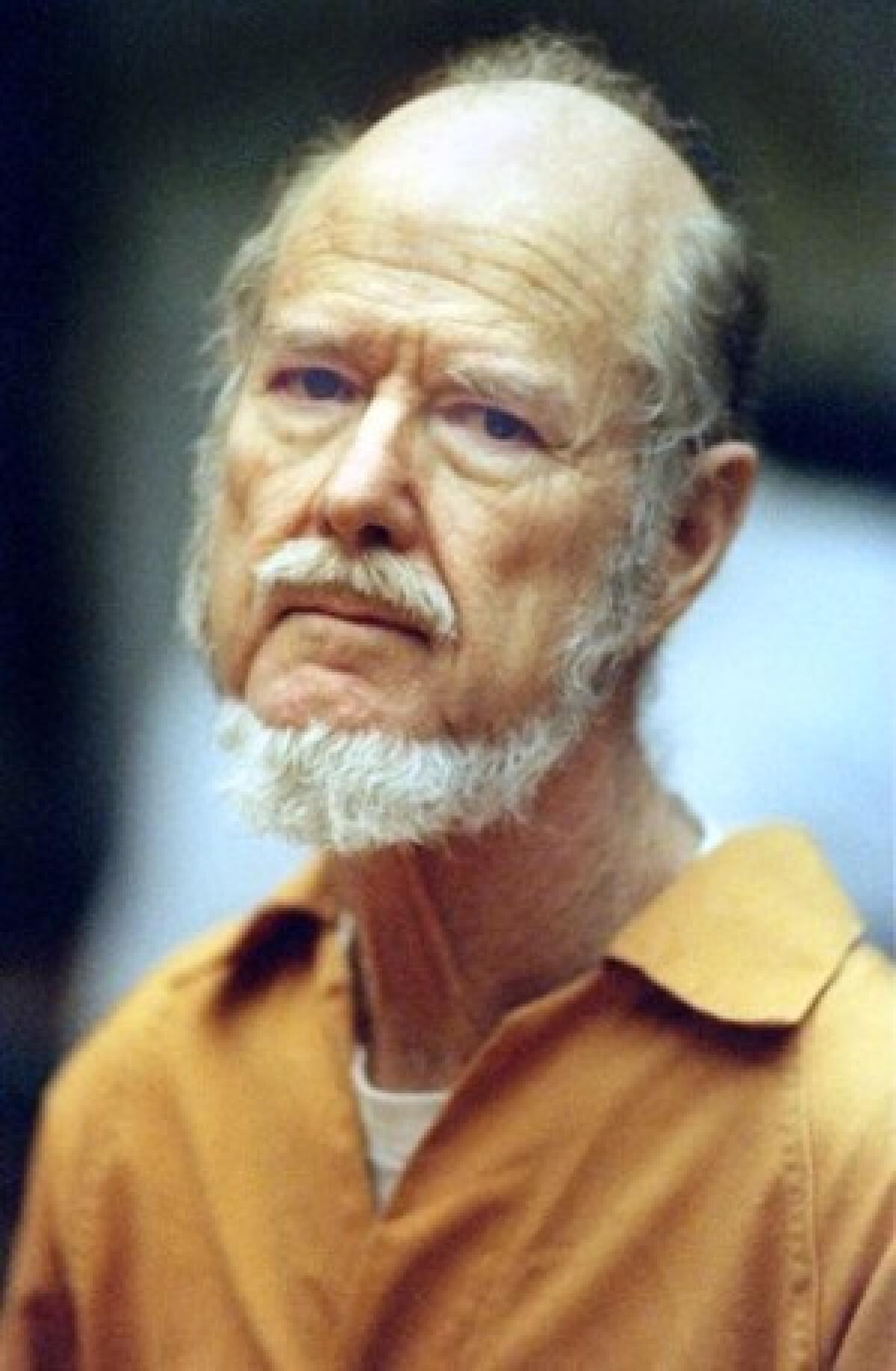

Richard K. Overton dies at 81; convicted of fatally poisoning his wife

- Share via

Richard K. Overton, the subject of one of Orange County’s most riveting trials who was convicted of murdering his wife, a popular school board member, by slipping her poisons in 1988, has died, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has confirmed. He was 81.

Overton died Thursday at a hospice in Northern California after he had been transferred from Folsom State Prison, where he was serving a life sentence, said Frank McAdams, co-author of “Final Affair,” a book on the criminal investigation. Overton died from advanced dementia and complications of diabetes, McAdams said.

The Overton trial had the workings of an Agatha Christie novel. Prosecutors revealed a story about the bookish itinerant college lecturer and business consultant who had grown jealous of his gregarious wife, Janet L. Overton, an elected trustee of the Capistrano Unified School District for 11 years, and about his suspicion that she had numerous affairs.

The Overtons’ 19-year marriage was full of mistrust, jealousy, money problems and infidelity, according to The Times’ coverage of the trial. Prosecutors suggested that one of Overton’s motives was his wife’s refusal to agree to a divorce, even though their marriage was in tatters.

Prosecutors alleged that Overton, a mathematician with a doctorate in psychology, slowly poisoned his wife, then 46, with toxic levels of cyanide and selenium so that in her final months, the otherwise cheerful woman suffered from dehydration and lesions so painful that the friction of her clothes became almost unbearable. Janet Overton died Jan. 24, 1988, as she and their teenage son, Eric, were about to set off on a whale-watching outing.

But the case’s bizarre twists didn’t end there. The criminal probe gained attention after Overton’s first wife, Dorothy Boyer, who raised four children with him, told authorities that Overton “tried to murder [her] through a process of slow poisoning” after they divorced in 1969. The couple had split after Boyer learned that while they were married, Overton had secretly married another woman, Caroline Draper, with whom he had a child. That marriage was annulled, and two years after Janet Overton’s death, he married a fourth time.

Investigators discovered that Boyer’s shampoo, milk and coffee contained selenium. Overton admitted to authorities that he adulterated Boyer’s food in the 1973 incident, but he was not charged. Both Boyer and Janet Overton suffered similar symptoms, including nausea, lesions and discolored and peeling feet.

Once Boyer disclosed the prior poisoning, coroner’s officials, who hadn’t been able to find the cause of Janet Overton’s death, reexamined tissue and blood from her autopsy and determined that she died from cyanide poisoning. Prosecutors said Overton had access to cyanide because he was part-owner in a mining operation.

Overton’s own obsessively detailed diaries helped convince jurors he was guilty. Coded in Spanish and Russian, the diaries recounted his wife’s whereabouts, listed the 17 men with whom he believed she was having affairs, and alluded repeatedly to a slow poisoning campaign using selenium.

Richard Kenneth Overton was born May 15, 1928, in Texas and studied math and Spanish at Abilene Christian College. He later earned a master’s and doctorate in psychology at the University of Texas. Over the years, he taught at various colleges and worked in the defense industry, according to news reports during the trial.

Up until his death, Overton maintained his innocence, McAdams said. Overton’s lawyer maintained during the trial that the level of cyanide found in Janet Overton’s system was too low to kill and could have been a byproduct of ulcer medication. But experts explained that the low levels of cyanide detected in her body were caused by the natural dissipation of the chemical over time.

During a jailhouse interview after he was found guilty, Overton told The Times that he felt the trial was like watching a “silly play.”

“I kept thinking, let’s leave this silly play and go home,” Overton said. “It took a long time to realize it was real because the whole thing has been so theatrical.”

The trial included testimony from a man, a Capistrano school official, who confirmed he had an affair with Janet Overton in the 1980s for several years. Overton conceded that he was angry over the extramarital affairs but said he was “too concerned about her health” to kill her.

In a sentencing report by an Orange County prosecutor at the time, Overton’s son, Eric, said what bothered him most was knowing that “his father is responsible for the death of the person he loved most in the world.”

A complete list of survivors was unavailable Saturday.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.