Sally Ride dies at 61; first American woman in space

- Share via

In the early days of the space program, astronauts were ex-Marines, Air Force officers and hot-shot pilots. Sally Ride got there a little differently: She answered a want ad.

In the late 1970s, NASA decided that, in addition to pilots, it needed some astronauts with more training in the sciences. More than 8,300 applied for a position, and she was one of only 35 chosen. Why, she later said, was a “complete mystery.”

Ride went on to become the first American woman sent into space, the youngest American sent into space and the first woman to make two trips. She also was the sole astronaut appointed to the Rogers Commission to investigate the 1986 explosion of the shuttle Challenger.

FOR THE RECORD:

An earlier version of this article suggested that Ride founded her company, Sally Ride Science, in 1991. She founded the company in 2001.

Ride died Monday at her home in La Jolla after a 17-month battle with pancreatic cancer. She was 61.

Her trip into space made Ride a household name and a symbol of the ability of women to break the glass ceiling, inspiring generations of young girls and women who came after her.

“Sally Ride broke barriers with grace and professionalism — and literally changed the face of America’s space program,” NASA Administrator Charles Bolden said in a statement. “The nation has lost one of its finest leaders, teachers and explorers. Our thoughts and prayers are with Sally’s family and the many she inspired. She will be missed, but her star will always shine brightly.”

“The impact of Sally Ride and women like her cannot be overestimated,” said Amy Mainzer, an astrophysicist who is a principal scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada-Flintridge. “She was an ‘existence proof,’” Mainzer told The Times. “She proved that it was possible to work in space physics and as a space scientist and be female at the same time. What she did was prove that you could make it all the way to the top and accomplish amazing things in these fields — and still have a pair of ovaries.”

The first woman in space was Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova in 1963, but she was a former textile worker who was sent into space as “window dressing.” The second was Svetlana Savitskaya, a former pilot who also was the first Russian woman space walker.

By contrast, Ride had much more extensive scientific training. She held a bachelor’s degree in physics from Stanford University and a master’s and doctorate in astrophysics from the same institution. Nonetheless, when NASA called her in 1978, she had to go back to school to study basic science and math, meteorology, guidance, navigation and computers. She also received flight instruction on a T-38 trainer jet, an experience that left her with a joy for flying.

In the week before her first shuttle flight, she told Newsweek that “I did not come to NASA to make history. It is important to me that people don’t think I was picked for the flight because I am a woman and it is time for NASA to send one.”

Ride served her time on the ground in preparation for her first flight. She was the capsule communicator for the second and third shuttle flights and helped develop the shuttle’s robot arm. On June 18, 1983, she entered space aboard the shuttle Challenger for mission STS-7, becoming the first American woman and, at age 31, the youngest person in space. The crew deployed two communications satellites and conducted pharmaceutical experiments.

With Ride and Col. John M. Fabian operating the robot arm, it performed the first deployment and retrieval of a satellite.

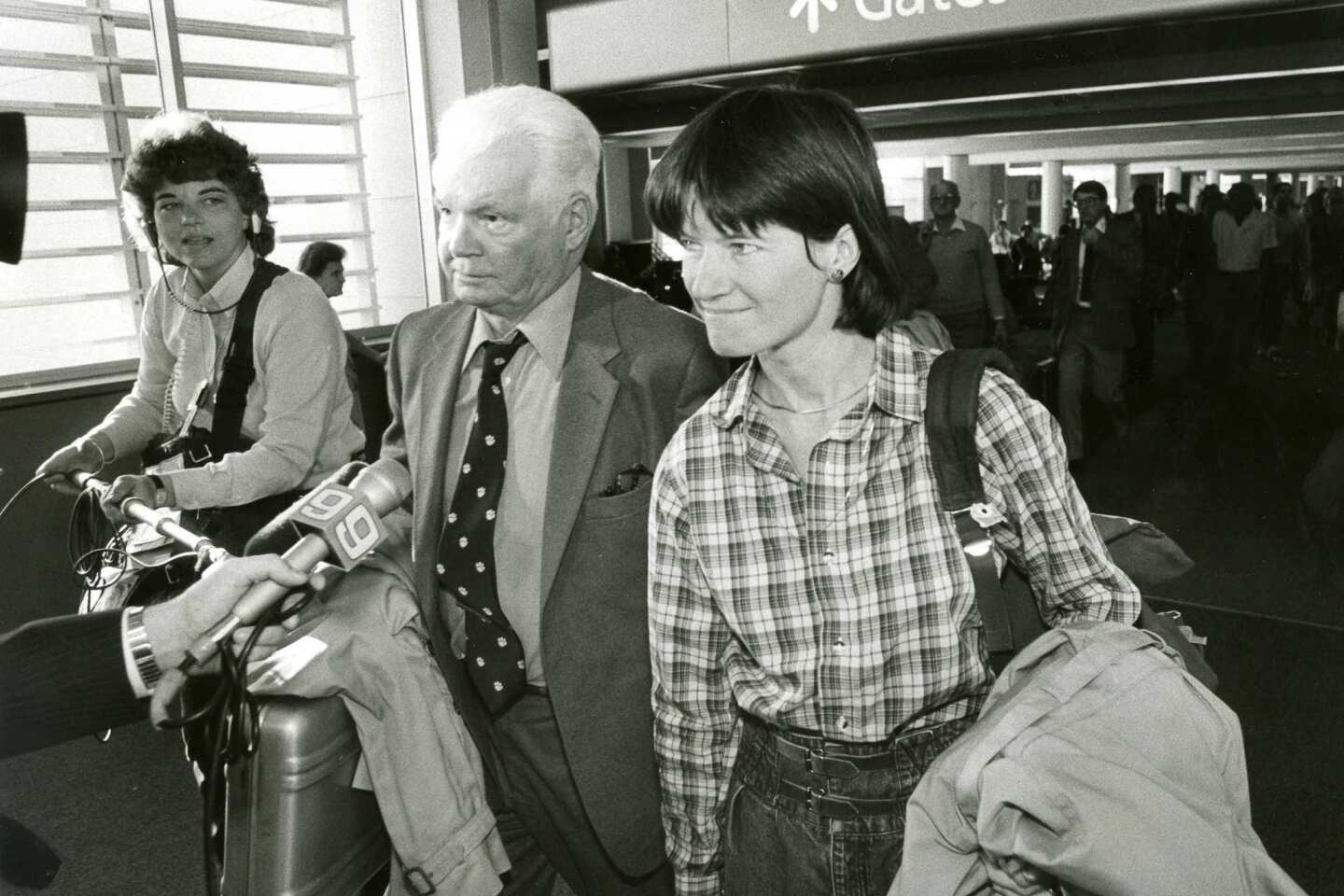

Shortly after landing, Ride said, “The thing that I’ll remember most about the flight is that it was fun. In fact, I’m sure it was the most fun that I will ever have in my life.”

Ride was again aboard Challenger for mission STS-41, which launched on Oct. 5, 1984. This time, the arm was put to some unusual uses, including scraping ice off the shuttle’s exterior and adjusting a radar antenna.

She was training for a third flight when the Challenger exploded in January 1986, and she was named to the Rogers Commission that investigated the disaster. During the probe, she was reportedly the only public figure to support Morton-Thiokol engineer Roger Boisjoly, who had warned of technical problems that led to the accident.

She was later quoted as saying that astronauts did not receive adequate warning about the potential dangers of the shuttle. She told the Chicago Tribune: “I think that we may have been misleading people into thinking that this is a routine operation.”

Ride subsequently transferred to NASA’s Washington headquarters and authored a report titled “Leadership and America’s Future in Space.” She also founded the agency’s Office of Exploration before resigning in 1987 to work at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Arms Control.

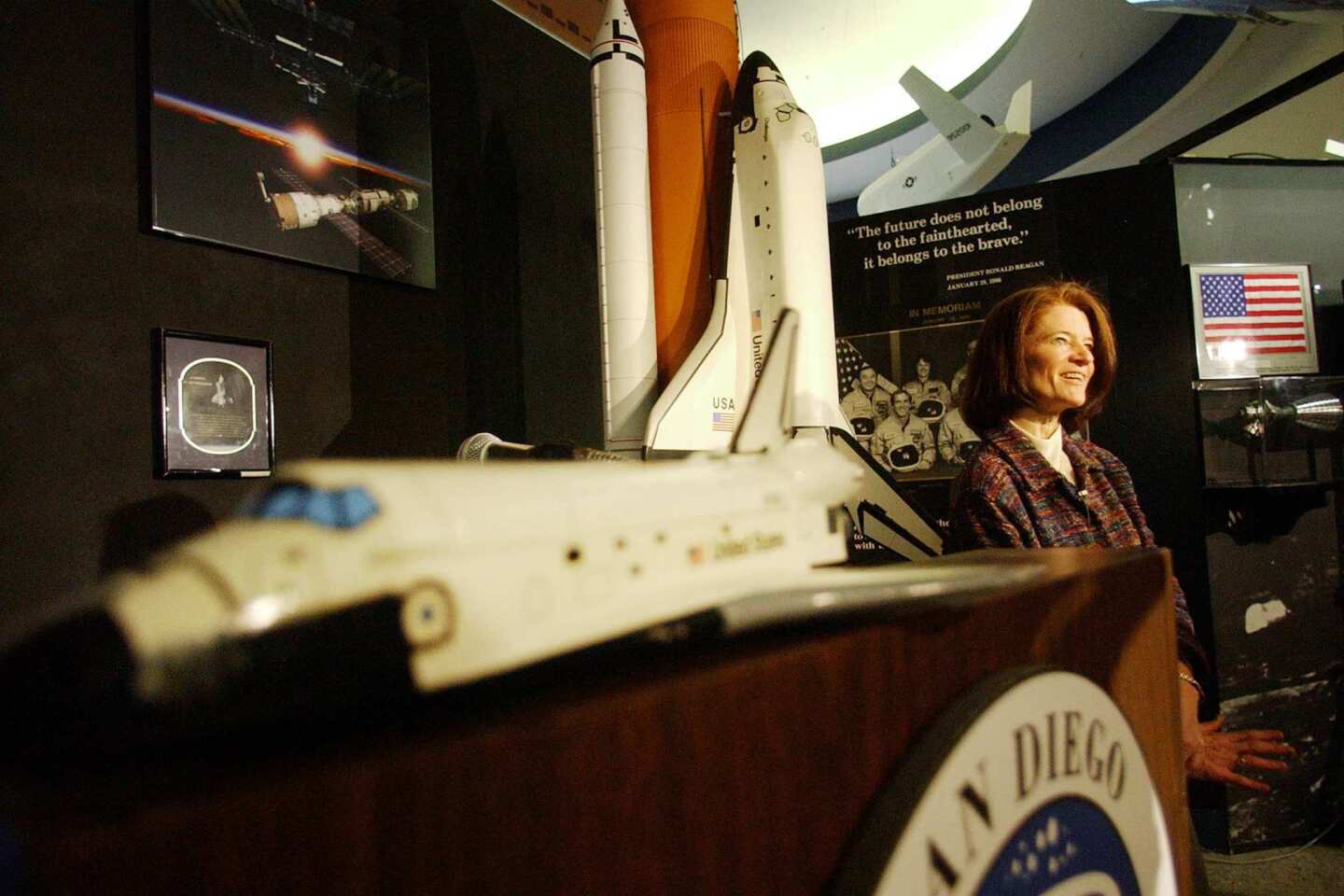

In 1989, she became director of the California Space Institute at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and a professor of physics at UC San Diego. In 2001, she founded her own company, Sally Ride Science, to encourage women and especially young girls to become interested in science. She also wrote five children’s books encouraging an interest in science.

Joy A. Crisp, a deputy project scientist at JPL, remembers watching with keen interest as Ride became the first American woman in space. The engineering and space-science fields were still very much a men’s club. “She was the first,” Crisp said Monday in an interview with The Times. “And after her came many other women. She made an important difference.”

“She reached out to so many young women,” Crisp said. “It got women and girls excited — they’d say: ‘Hey, I could really do this.’ She made it fun and interesting. She clearly saw that it was important to be that role model. It was something she could do to give back.”

Sally Kristen Ride was born May 26, 1951, in Encino. A straight-A student, she was easily bored in school until her interest in science was stirred by a high school physiology teacher, Elizabeth Mommaerts.

Ride was also a tomboy and especially adept in tennis. She took lessons and was ranked 18th nationally on the junior circuit, receiving a partial scholarship to Westlake School for Girls, now Harvard-Westlake School.

Tennis pro Billie Jean King saw her play and told her that she could become a professional, and Ride enrolled at Swarthmore College to play tennis. But she decided that she didn’t have sufficient dedication to the game and switched her interest to physics and transferred to Stanford.

While at NASA, Ride had one other first. On July 26, 1982, she and Steven Alan Hawley became the first active astronauts to be married. During a hearing, Rep. Larry Winn Jr. (R-Kan.) asked her how she would feel when Hawley was in space while she remained on the ground. “I am going to be a very interested observer,” she replied.

The two were divorced in 1987.

Ride was the only person to serve on both the panel investigating the Challenger disaster and the panel investigating the 2003 shuttle Columbia disaster.

She received a number of honors, including twice being awarded the NASA Space Flight Medal. She has been inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the Astronaut Hall of Fame. California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger inducted Ride into the California Hall of Fame in 2006, and incoming President Clinton named her to his transition team.

Ride is survived by Tam O’Shaughnessy, her partner of 27 years; her mother, Joyce; her sister, Karen, known as “Bear”; and a niece and nephew.

Times staff writer Scott Gold contributed to this report.

Twitter: @LATMaugh

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.