Solomon Burke dies; singer’s voice was as big as his soul

- Share via

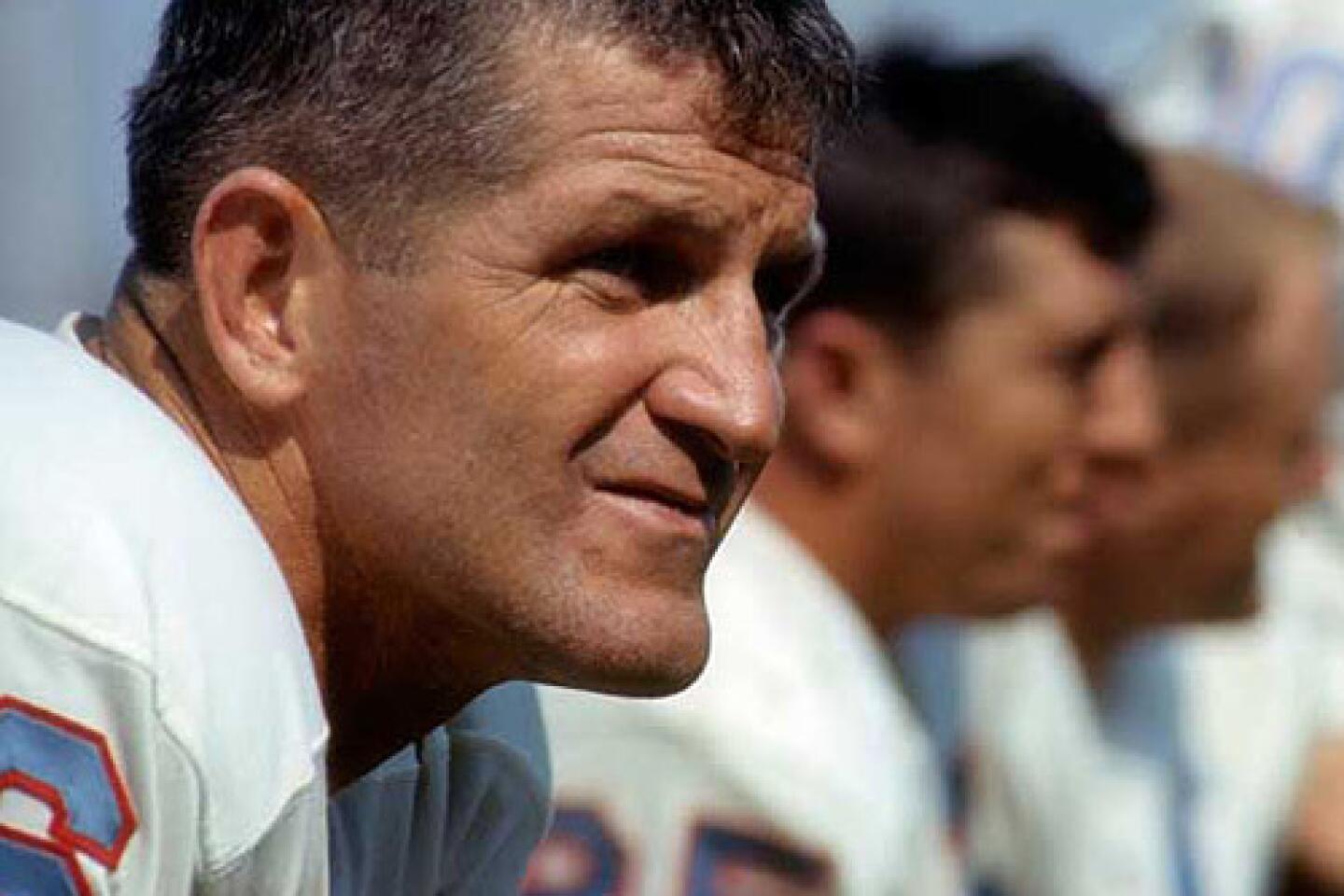

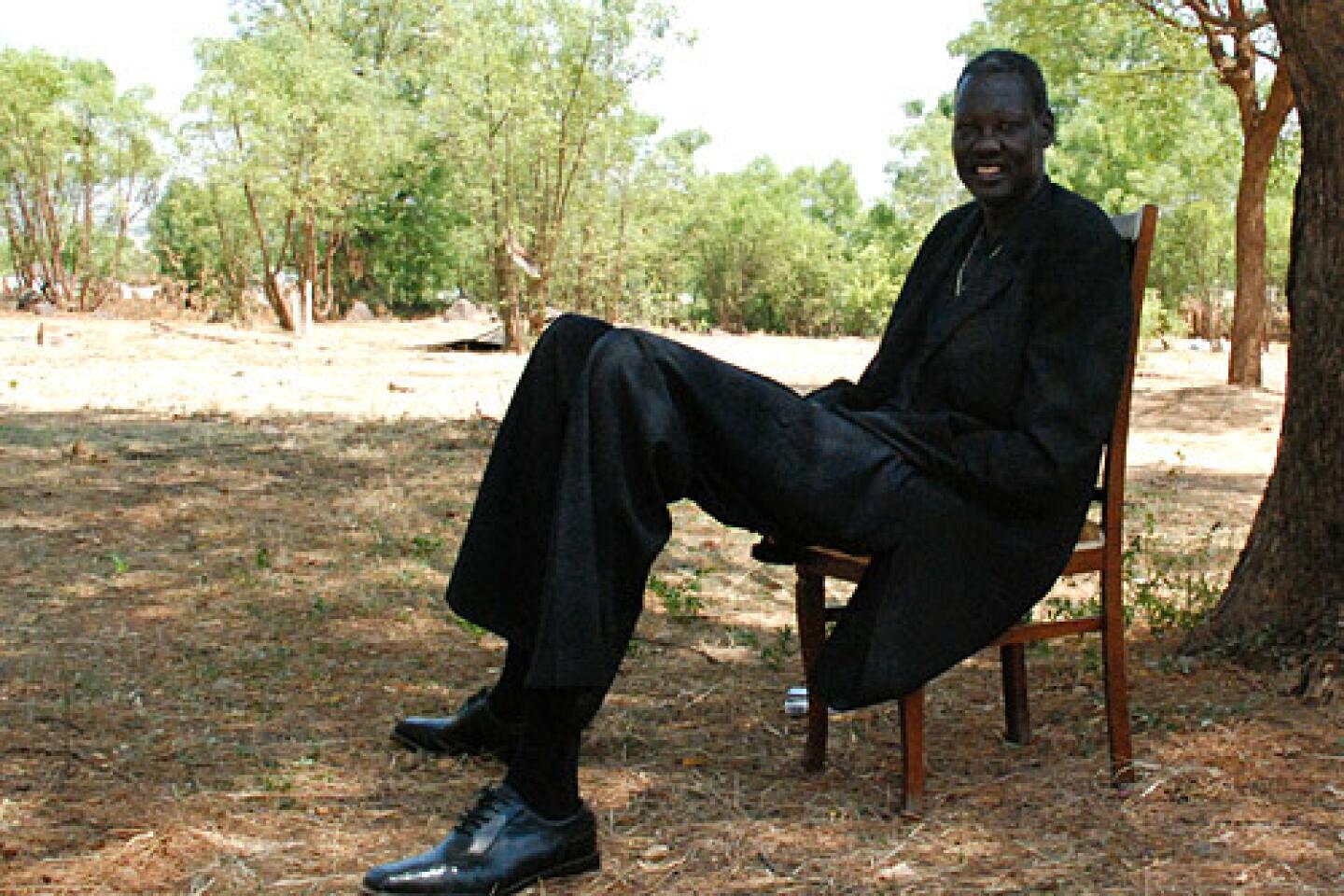

Solomon Burke, a pioneering singer-songwriter of so-called sweet soul music whose powerful ballads in the 1960s were a major influence on a generation of rock, R&B and pop vocalists, has died. He was in his early 70s.

Burke died early Sunday morning of natural causes at an Amsterdam airport, his family announced on his website. He had flown there from Los Angeles for a concert.

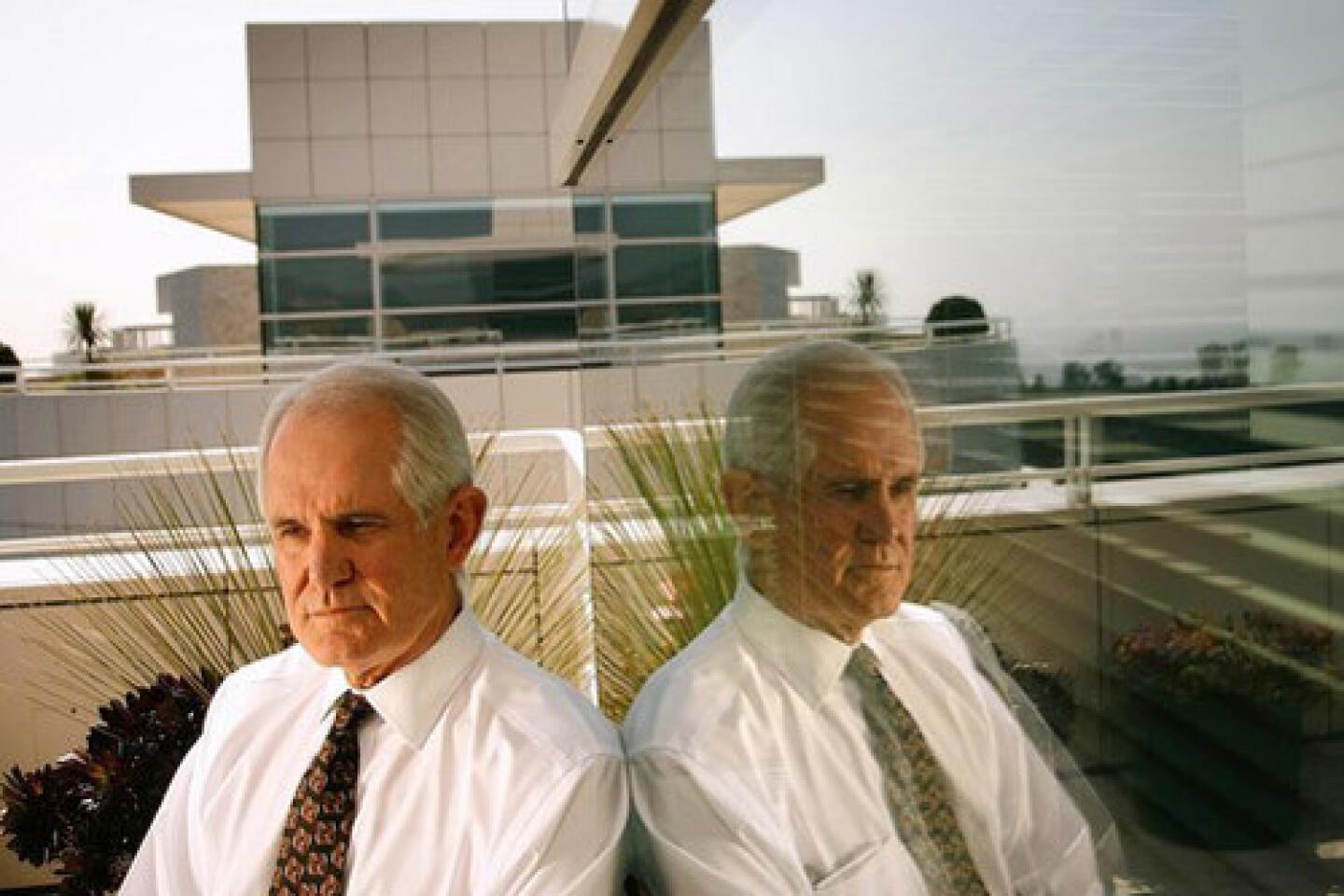

“He was the founding father of what was defined as soul music in America in the 1960s. He was a major player,” Tom Reed, author of the 1992 book “The Black Music History of Los Angeles: Its Roots,” told The Times on Sunday.

Sam Moore of the R&B duo Sam & Dave pronounced in Rolling Stone magazine in May: “There will never be another Solomon Burke.”

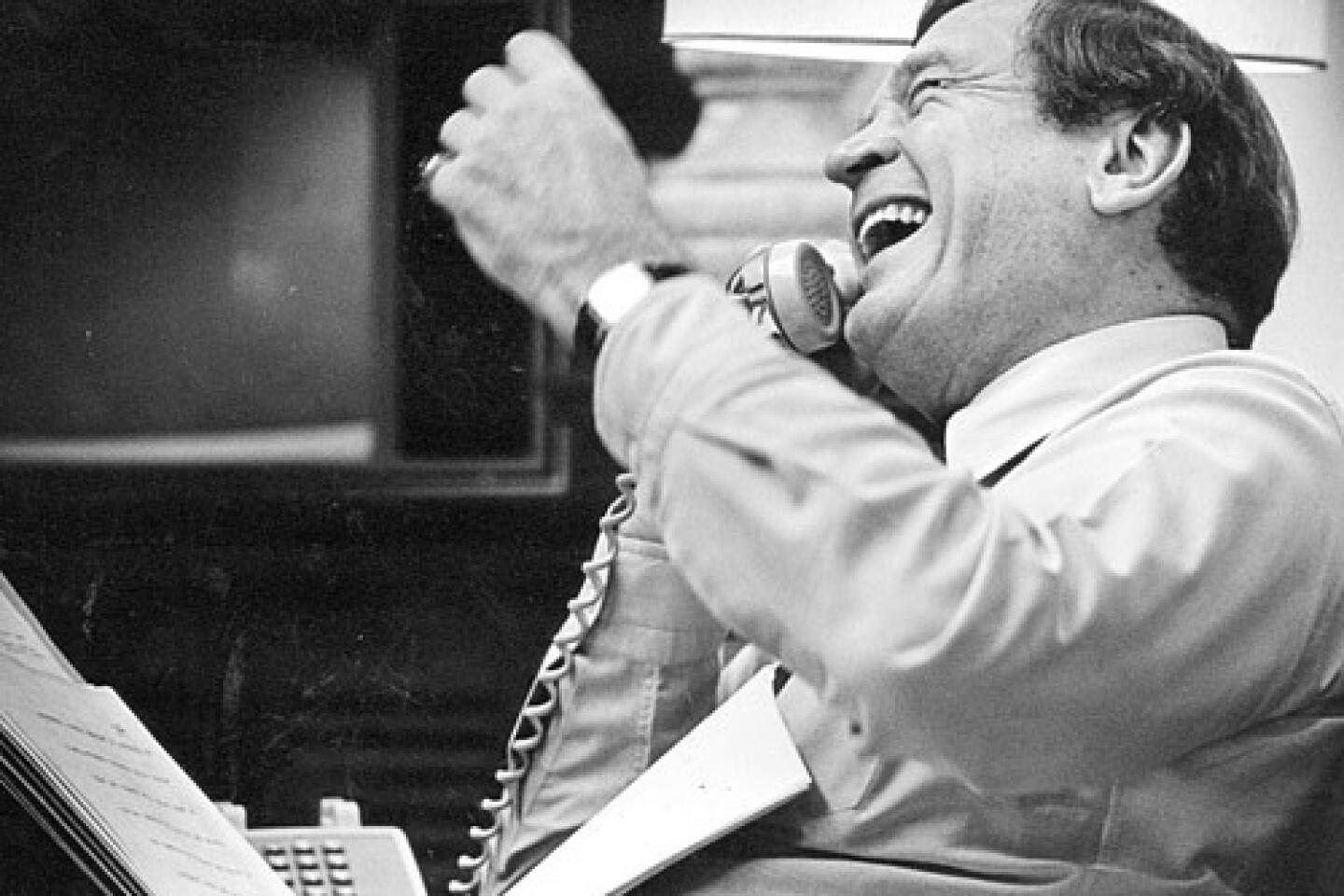

“When I first saw him, I couldn’t believe that one man could have a voice that big,” Moore said. “He could rock a house. He was that good.”

That voice was responsible for some of classic soul music’s most essential songs of the 1960s, prime examples of the sweet soul music that harnessed the earnestness of the Southern gospel tradition in which Burke was raised to create emotionally charged R&B moments.

Among his career highlights were “Tonight’s the Night,” an R&B and pop hit and “Cry to Me,” an ode to loneliness and desire that is remembered for its use in a seductive scene in the 1987 film “Dirty Dancing.”

His 1964 hit “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love” was covered by the Rolling Stones and Wilson Pickett, among many others. It too achieved heightened fame in a movie — 1980’s “The Blues Brothers” with Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi.

When Burke was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2001, his rendition of the song stole the show from Aerosmith, Steely Dan and other inductees, pop critic Robert Hilburn wrote in The Times in 2002.

His signature single was 1965’s “Got to Get You Off of My Mind,” which the hall of fame calls one of the premier soul hits of the 1960s. Written by Burke, it features his smooth, solid voice lamenting the death of a love affair.

In 1961 he signed with Atlantic Records, which was looking for church-trained singers with commanding voices. Over the years, the label has been home to Otis Redding, Pickett, Ray Charles and many others.

Even with his talent-heavy roster, Atlantic producer Jerry Wexler once described Burke as “the best soul singer of all time.”

Although Burke toured regularly in the U.S. and Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, he was averaging less than a dozen shows a year by the 1990s.

Still, Burke consistently delivered new songs, both secular and gospel, and received a late career boost with a comeback recording, “Don’t Give Up on Me,” which received a Grammy Award in 2003.

Since he was 7, Burke had also been a preacher. He was preparing to deliver a sermon in 2002 at the Los Angeles church he founded and ran — the House of God for All People — when he discovered the microphone wasn’t working.

The singer, whose voice matched his more than 300-pound frame, responded by saying: “So what? I wasn’t born with a microphone. I was born with a voice.”

He was born James Solomon McDonald in Philadelphia on March 21. He said he was born in 1940, but several biographical references give his birth year as 1936.

His surname came from his stepfather, Vincent Burke, who loved him “as his own,” the younger Burke later said. He had no memory of his biological father, and he was always on the run from his temperamental mother, Burke said in the Rolling Stone article.

He often ended up a few doors away at the home of his grandmother, a spiritual healer who had formed her own church.

In his youth, he was so charismatic in the pulpit that he was known as the Boy Wonder Preacher. The first sign of a royal persona was evident in the cape that he wore only on Sundays, made from his “blankie.”

By age 13, he was hosting a gospel program on Philadelphia radio and broadcasting from a church of his own.

The power of his on-air voice caught the attention of the wife of a Philadelphia disc jockey, which led him to record for the Apollo label in his teens.

When Burke realized that a business manager in the 1950s was pocketing some of his concert fees, the manager threatened to blackball him and the singer found it hard to get concert dates.

To support his family, he went to mortuary school and worked in a Philadelphia funeral home owned by his aunt. After he became successful musically, he invested in a chain of funeral homes.

“Solomon Burke knock you dead from the bandstand. Then he gift-wrap you for the trip home,” fellow soul vocalist Joe Tex said in the 1994 book “Nowhere to Run.”

Burke’s family would grow to include 14 daughters, seven sons, 90 grandchildren and 19 great-grandchildren, according to his website. He was married at least three times.

At his home in Los Angeles, Burke greeted visitors from a red velvet throne in his living room, where he kept his Grammy and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame awards on a nearby mantel.

valerie.nelson@latimes.com

randall.roberts@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.