William Emerson dies at 86; Newsweek journalist covered the South

- Share via

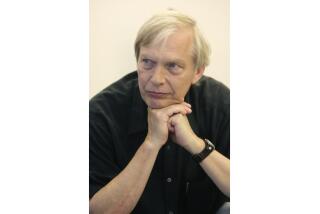

William A. Emerson Jr., who covered civil rights flash points as part of a cadre of gutsy Southern reporters and later served as editor in chief of the Saturday Evening Post, has died. He was 86.

Emerson, whose health had declined after a stroke, died Tuesday at his home in Atlanta.

A boisterous, outsize figure in an era of colorful New York magazine editors, Emerson stood 6-foot-3, with a booming voice that took over any room. His gifts as a phrasemaker made him a sought-after speaker. Last month, he included hundreds of speeches on wide-ranging subjects including journalism and religion with papers he donated to Emory University.

A veteran of the China-Burma-India theater in World War II, Emerson worked at Collier’s magazine in New York after graduating from Harvard University in 1948.

He was appointed Newsweek’s first bureau chief covering the South in 1953, one year before the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education, which ended public school segregation and triggered years of resistance and violence across Emerson’s native region.

In a memoir, former Newsweek editor Osborn Elliott described Emerson as “a great, rangy, bodacious man who flapped his arms when he walked and enchanted when he talked” and who “launched a tradition of sharp and sensitive Newsweek reporting from the South.”

Emerson wrote about cross burnings by the Ku Klux Klan in the piney woods of Florida and school integration fights from Nashville to New Orleans, giving firsthand descriptions of bomb blasts and the experience of walking a shrieking, spitting gantlet with a mother intent on getting her young daughter to class and home again. In Montgomery, Ala., he covered the historic bus boycott and the emergence of its leader, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Summing up those heady days and the group of competing reporters, many of them fellow Southerners, Emerson told an interviewer in 2006, “We knew we had to just tell the damn truth. The truth may be plenty good or plenty bad, but believe me, it’s always plenty.”

For a Newsweek cover article about author William Faulkner, Emerson headed to the Nobel laureate’s Mississippi home. Though a sign at the driveway told him to go away, Emerson knew Faulkner sometimes relented. He relished telling the story from there, in many variations: how he ventured up the driveway anyway, attracting first dogs and then a shirtless Faulkner himself, who grumbled a few words and then calmly told someone to get his shotgun.

Emerson later held a succession of editing posts in New York at Newsweek and then the Saturday Evening Post, where he was promoted to editor in chief in 1965. When the magazine sank in 1969, he joked that he floated out clinging to the frame of a Norman Rockwell painting that hung in his office.

His era at the Post was a time of tumult in news gathering as well as society.

As the so-called New Journalism was developing, Emerson worked with such practitioners as Joan Didion. He arranged a first-person article, “My Ordeal in Oxford,” by James Meredith, whose enrollment at the University of Mississippi set off riots; it was a scoop in the competitive magazine world, noted the authors of the Pulitzer prize-winning history, “The Race Beat.”

When President Kennedy was assassinated, Emerson, then executive editor, helped recast the entire issue in days to meet a printing deadline. With a Rockwell portrait of JFK as its cover, it included tributes by former President Eisenhower and historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

William Austin Emerson Jr. was born in Charlotte, N.C., on Feb. 28, 1923. His family later moved to Atlanta. Emerson was married to Lucy Kiser for 56 years before her death in 2005. They had five children.

After leaving publishing, Emerson taught journalism at the University of South Carolina. He was the author or coauthor of a number of books, including a colorful layman’s biography titled “The Jesus Story” and “Sin and the New American Conscience.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.