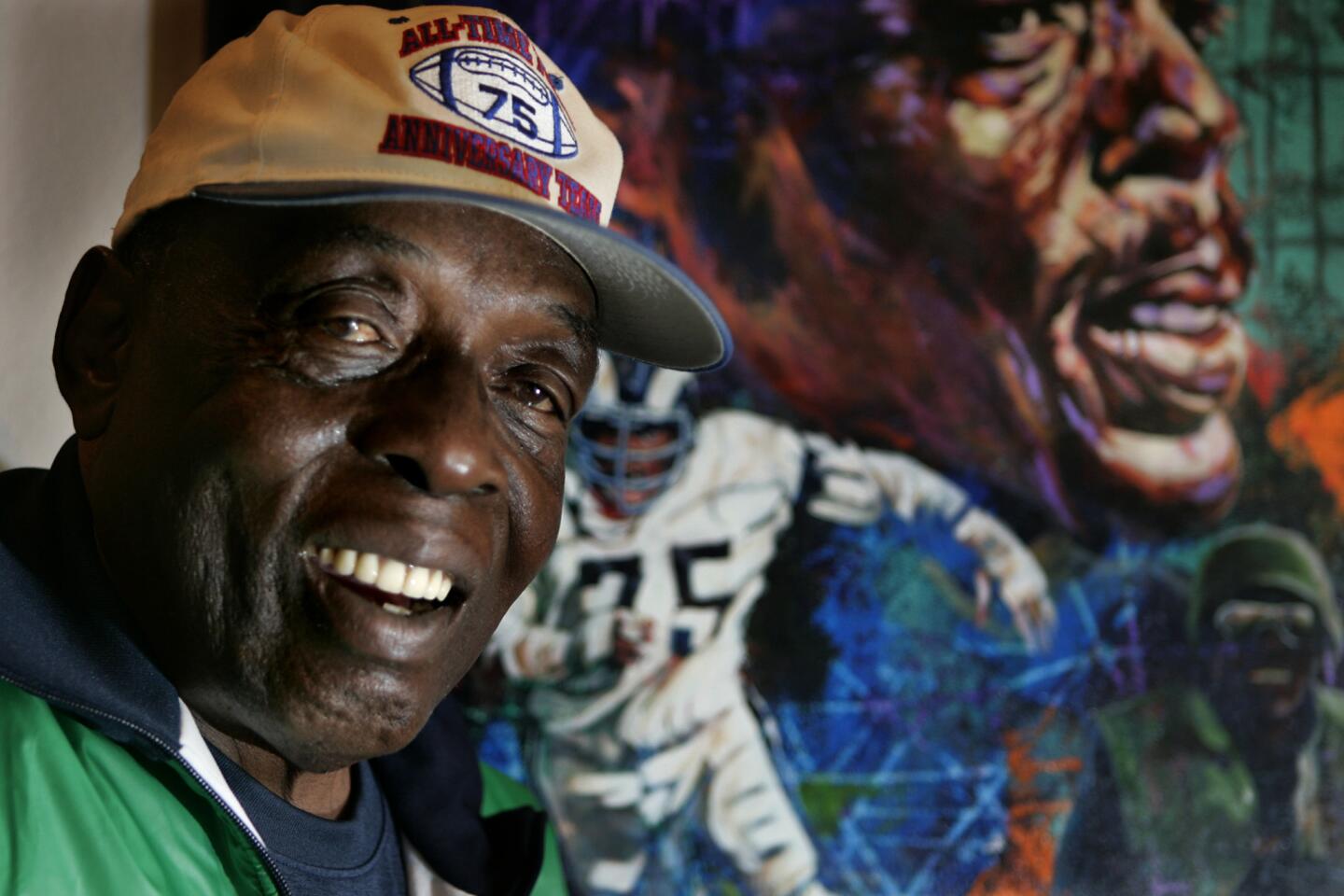

Zhuang Zedong dies at 72; helped get ‘pingpong diplomacy’ rolling

- Share via

It might have been a chance meeting or a cunning act of propaganda, but the encounter more than 40 years ago between two pingpong champions — one Chinese, the other American — launched what President Nixon would call “the week that changed the world.”

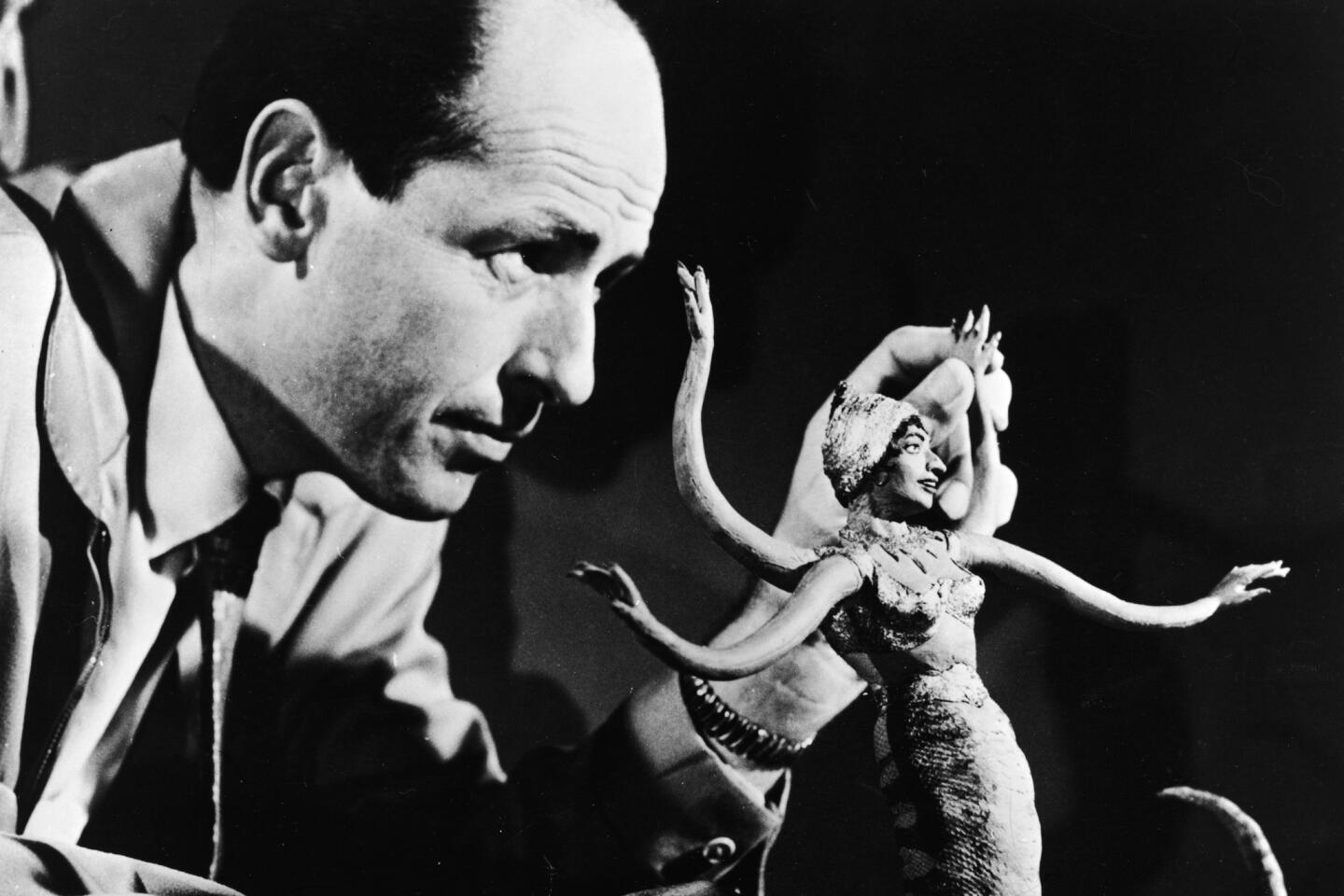

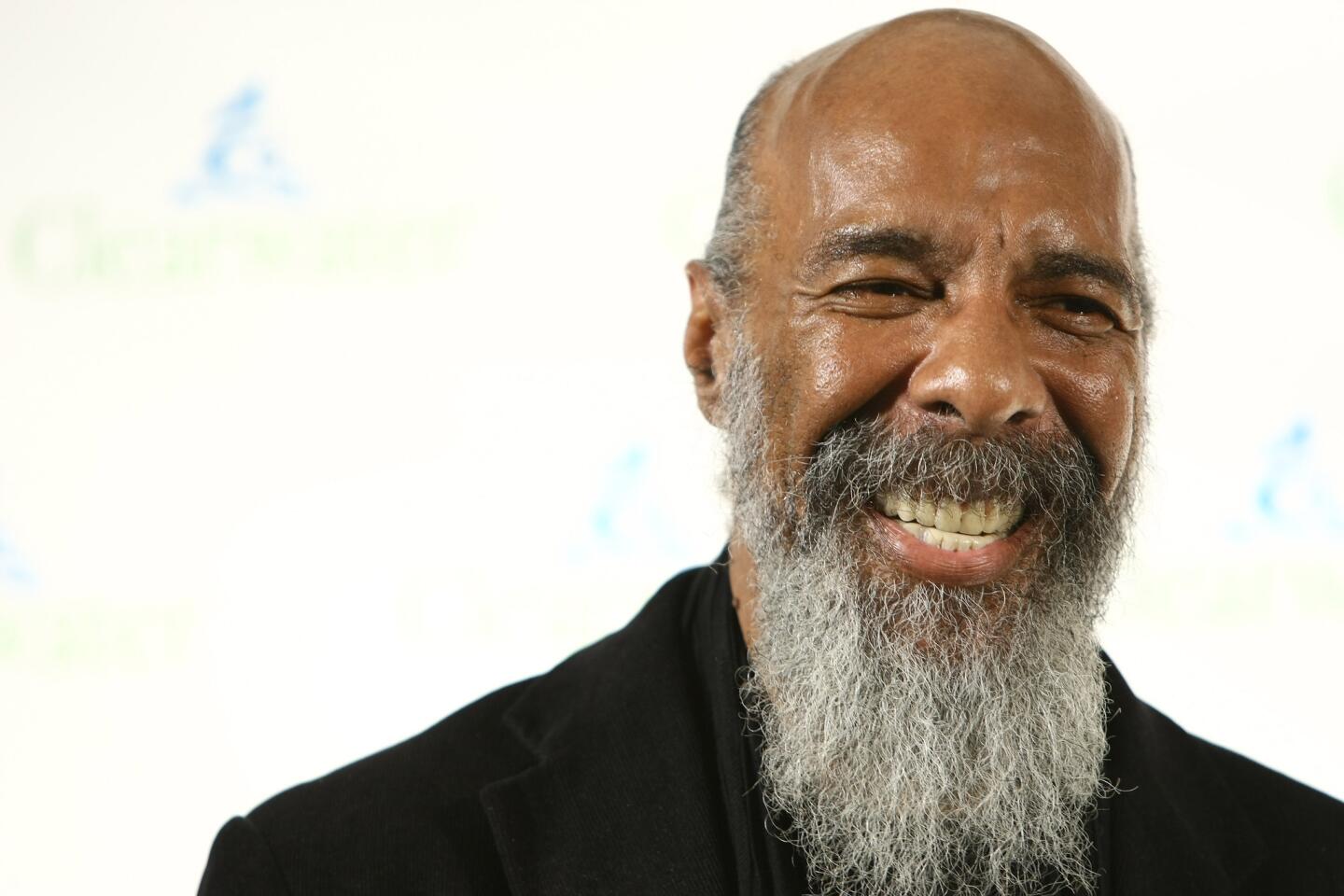

Zhuang Zedong, the captain of the Chinese team competing at the 1971 World Table Tennis Championships in Japan, was at the back of his team’s bus when its doors swung open for a straggler, American juniors champion Glenn Cowan.

With the United States and China still stuck in the Cold War, none of the Chinese players dared utter a word to the American. Ten minutes passed in silence.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

Then, Zhuang, against the advice of his teammates, made his way up the aisle to the lanky, long-haired player from Santa Monica College. Through an interpreter, he asked Cowan’s name and offered friendship and a silk portrait of China’s famous Huangshan Mountain. When they arrived at the main tournament hall a few minutes later, the Chinese athlete and his new acquaintance stepped off the bus into history.

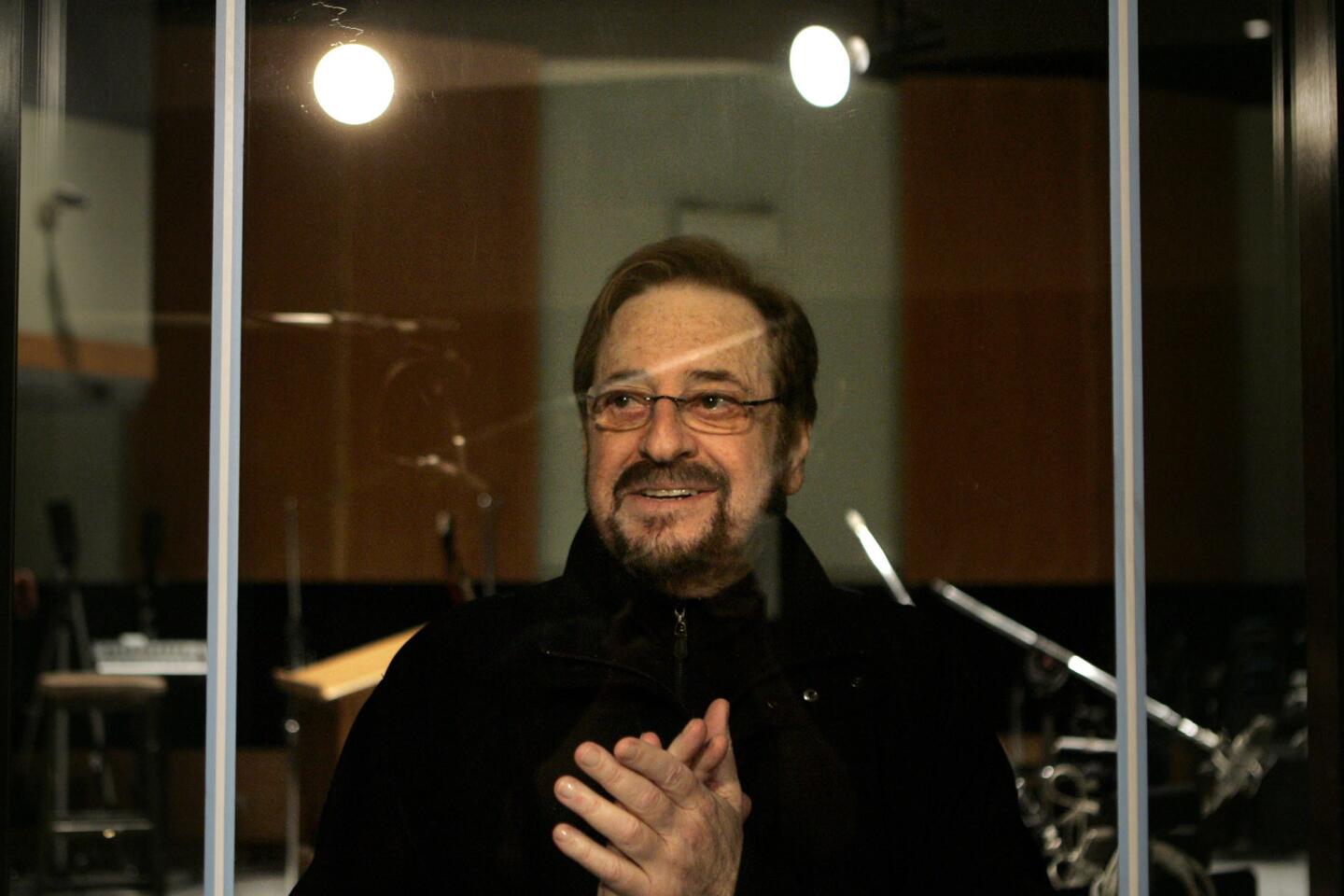

Zhuang, whose gesture launched “the ping heard around the world,” died Sunday in Beijing. He was 72 and had cancer, according to the New China News Agency.

A three-time world table-tennis champion, Zhuang became an unlikely ambassador for a country that had been closed to Americans since the communist takeover of China in 1949. After the April 4, 1971, meeting on the bus, photos of a smiling Zhuang and Cowan flashed around the world, presenting the Chinese government with a unique opportunity: To the astonishment of much of the world, it invited the American pingpong team to Beijing. On April 10, Cowan, his teammates and a few journalists became the first group of U.S. citizens to visit China in two decades.

Less than a year later, in February 1972, Nixon visited China in a historic move toward normalizing relations with a longtime nemesis. In April, the Chinese and American teams toured the U.S. in a riveting display of “pingpong diplomacy.”

The unusual merger of statecraft and sports “turned the familiar big-power contest into a whole new game,” Time magazine wrote.

Zhuang, whose athletic prowess had made him a national hero, was not shy about claiming credit for the stunning turnabout.

“The Cold War,” he told a reporter years later, “ended with me.”

The rapprochement of East with West was, of course, far more complicated than that. Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s national security advisor, was among those who questioned whether Zhuang’s befriending of Cowan had been a fluke. “One of the most remarkable gifts of the Chinese is to make the meticulously planned appear spontaneous,” he wrote in his memoir “White House Years.”

For some months before the fateful pingpong encounter, Nixon and Kissinger had been conducting top-secret exchanges with their Chinese counterparts, Communist Party Chairman Mao Tse-tung and Prime Minister Chou En-lai. When China, emerging from the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, decided to send a team to the World Table Tennis Championships in Nagoya, Japan, in 1971, Chou sent word that Chinese players should have friendly contacts with teams from other countries.

“There was a lot of big politics behind it,” Maochun Yu, who teaches East Asian and military history at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., said of Zhuang’s star turn on the world stage.

Zhuang “was politically astute and also he was a three-time champion, so he had a certain hubris and prestige to act with little bit of freedom,” Yu said. “But without Chou’s specific instructions he would not have shaken hands with Mr. Cowan, let alone give him the gift. Nothing was specifically instructed, but he understood what needed to be done.”

The American team was feted in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, hosted by Chou himself. The next year, when the Chinese players toured several U.S. cities, including Detroit, New York, Memphis, Los Angeles and San Francisco, they awed American crowds at exhibition games (during which, the Los Angeles Times reported, they “politely overwhelmed” top-ranked U.S. competitors).

Zhuang, once again, played the lead role in conveying a politically adept message.

“Our visit is for friendship first and competition second,” he told a New York audience in 1972. “Losing or winning is something passing. Friendship is something everlasting.”

“He said what he was supposed to say and said it smoothly,” recalled China scholar and UC Riverside professor Perry Link, who served as an interpreter for the Chinese team in 1972.

Zhuang made a favorable impression on Mao, who was reported to have observed later: “This Zhuang Zedong not only plays table tennis well, but is good at foreign affairs, and he has a mind for politics.” The pingpong star became a favorite of Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, and was named minister of sports in 1975 and a member of the Chinese Communist Party’s powerful Central Committee.

His fortunes changed in 1976, when Mao died and his widow fell from favor, along with other members of the notorious Gang of Four, which had been responsible for much of China’s turmoil during the Cultural Revolution. Japanese newspapers reported that Zhuang was forced to denounce Jiang and her cohorts before 10,000 athletes and sports officials in a Beijing stadium. He was incarcerated for four years and exiled to the northern Chinese province of Shanxi until 1984, when he was allowed to return to Beijing.

Zhuang was born in Yangzhou, China, on Aug. 25, 1940, and began playing table tennis at 11. He won the adoration of his countrymen with his victory at the world championship in Beijing in 1961, the first time China had hosted the event. He won again in Czechoslovakia in 1963 and in Yugoslavia in 1965.

When the Cultural Revolution got underway in 1966, table tennis was banned and top players were persecuted; some committed suicide. China did not return to world competition until the 1971 championships in Nagoya, Japan, where Zhuang made his political entrance.

Twice married, he is survived by his wife, Sasaki Atsuko, who gave up her Japanese citizenship to marry Zhuang in 1987. Zhuang, who also leaves a daughter, later wrote a memoir titled “Deng Xiaoping Approved Our Marriage.”

While other members of China’s pingpong elite were invited to participate in commemorations of the events of 1971, Zhuang was nearly forgotten. He coached teenagers in Beijing for several years, retiring in 2000.

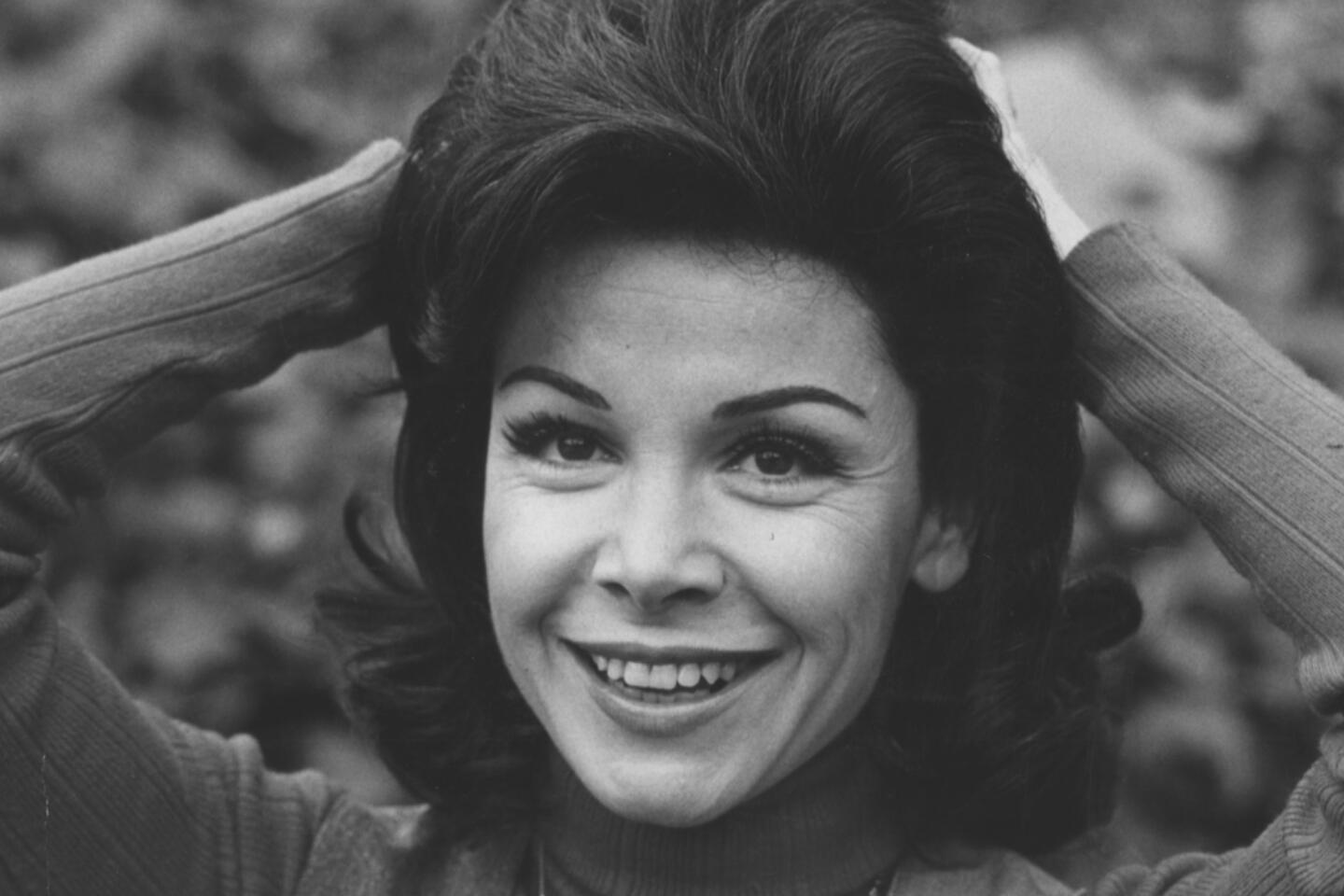

Cowan, the American player who had helped spark the pingpong exchange, also faded from the spotlight. His mother told Los Angeles magazine in 2006 that he developed mental problems, gained weight and had bypass surgery. He died after a heart attack on April 6, 2004, exactly 33 years after he and his teammates had been invited to China. Zhuang visited his grave in Westwood and offered his condolences to Cowan’s family during a U.S. visit in 2007.

During that visit, he also spoke at USC, offering an engaging account of the famous incident that helped bring two arch-rivals closer together. “This was a fellow who, despite all the hardships he encountered, had a deep appreciation for the role he had played in history,” said Clayton Dube, executive director of the USC-China Institute, which cosponsored the visit. “He made this American feel welcome. It speaks to the power of the small gesture.”

Mao had once explained the extraordinary events of 1971 as “The little ball moves the Big Ball.” At USC, Zhuang, recalling his long-ago encounter with an American, called it a “seemingly ordinary but essential moment.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.