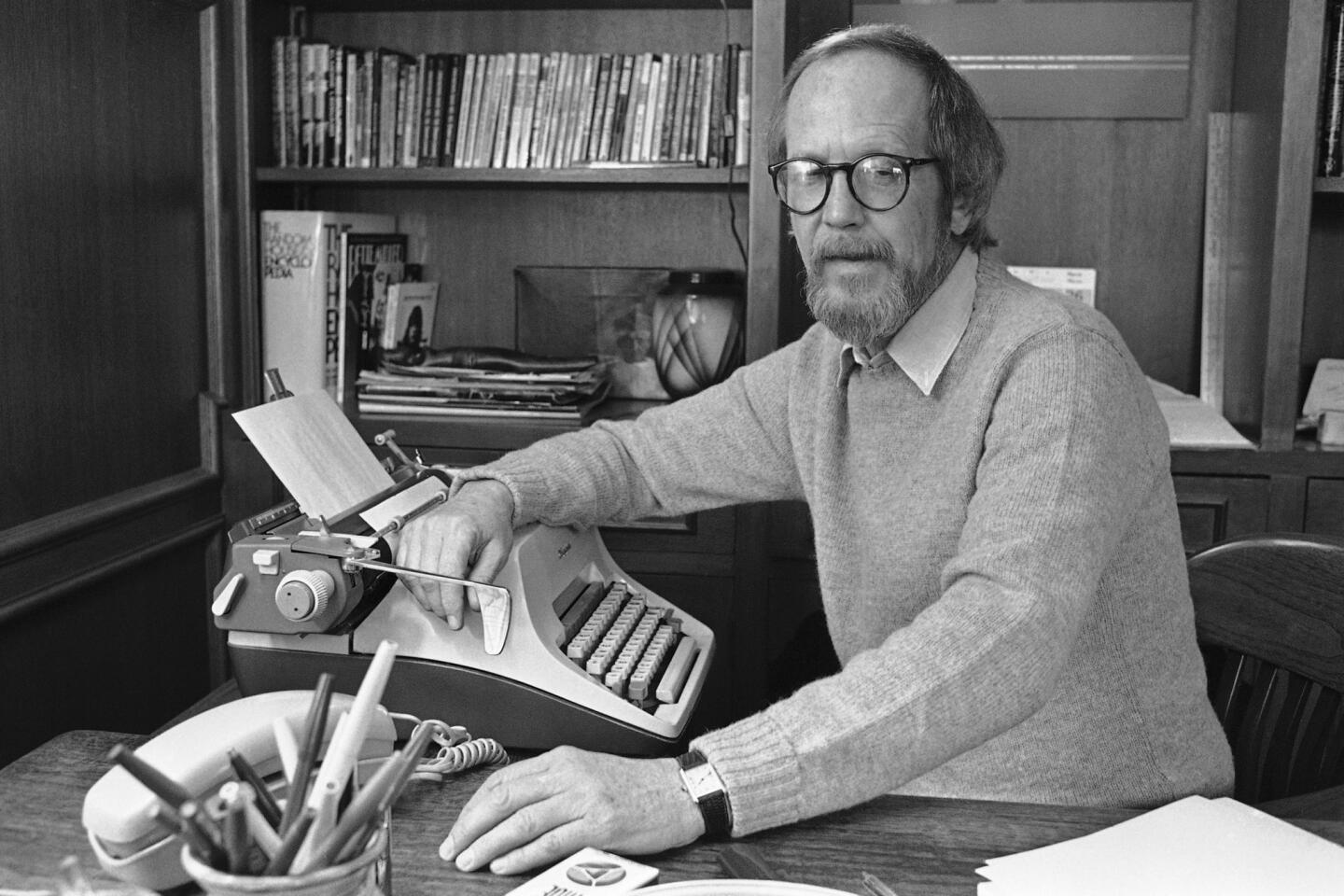

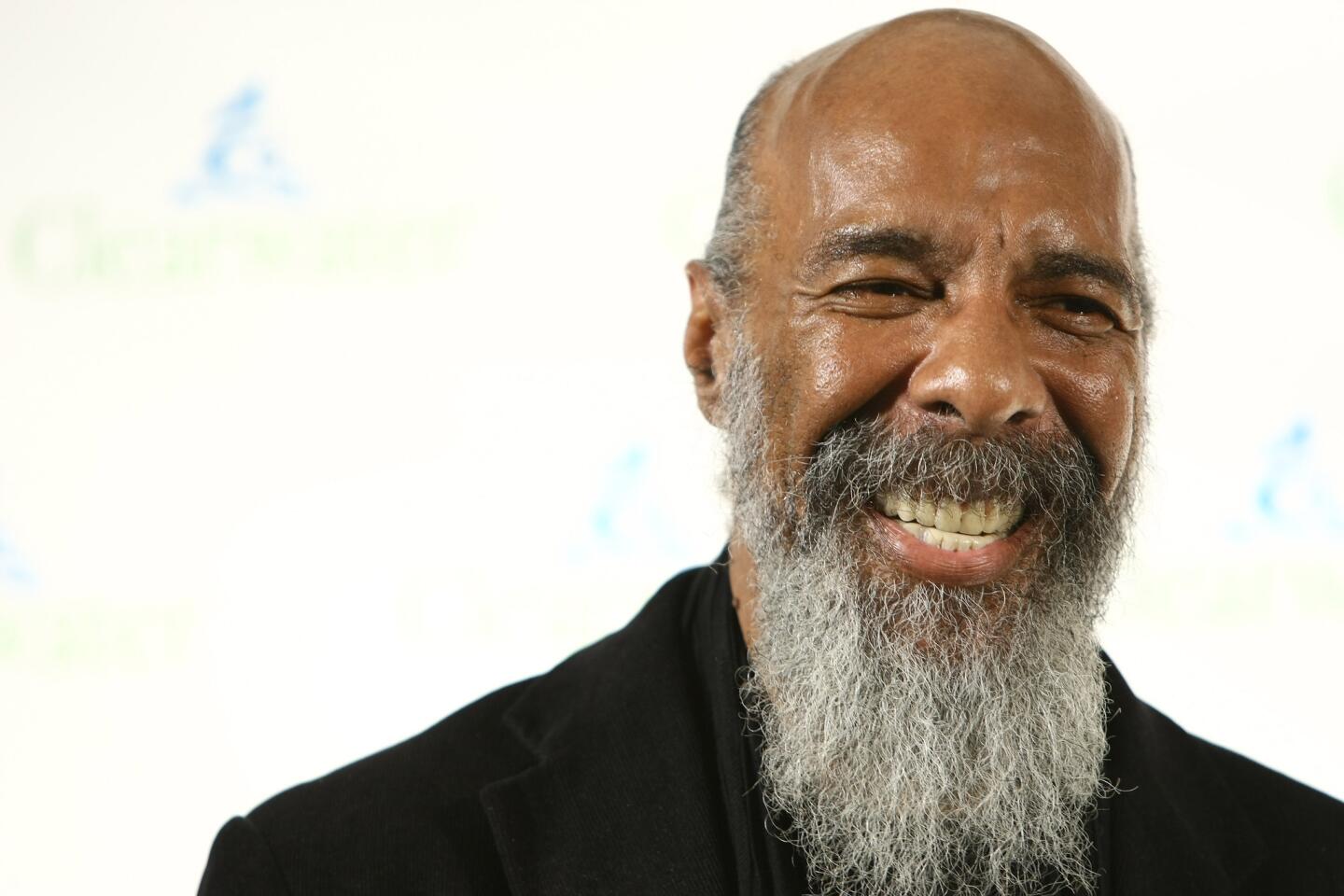

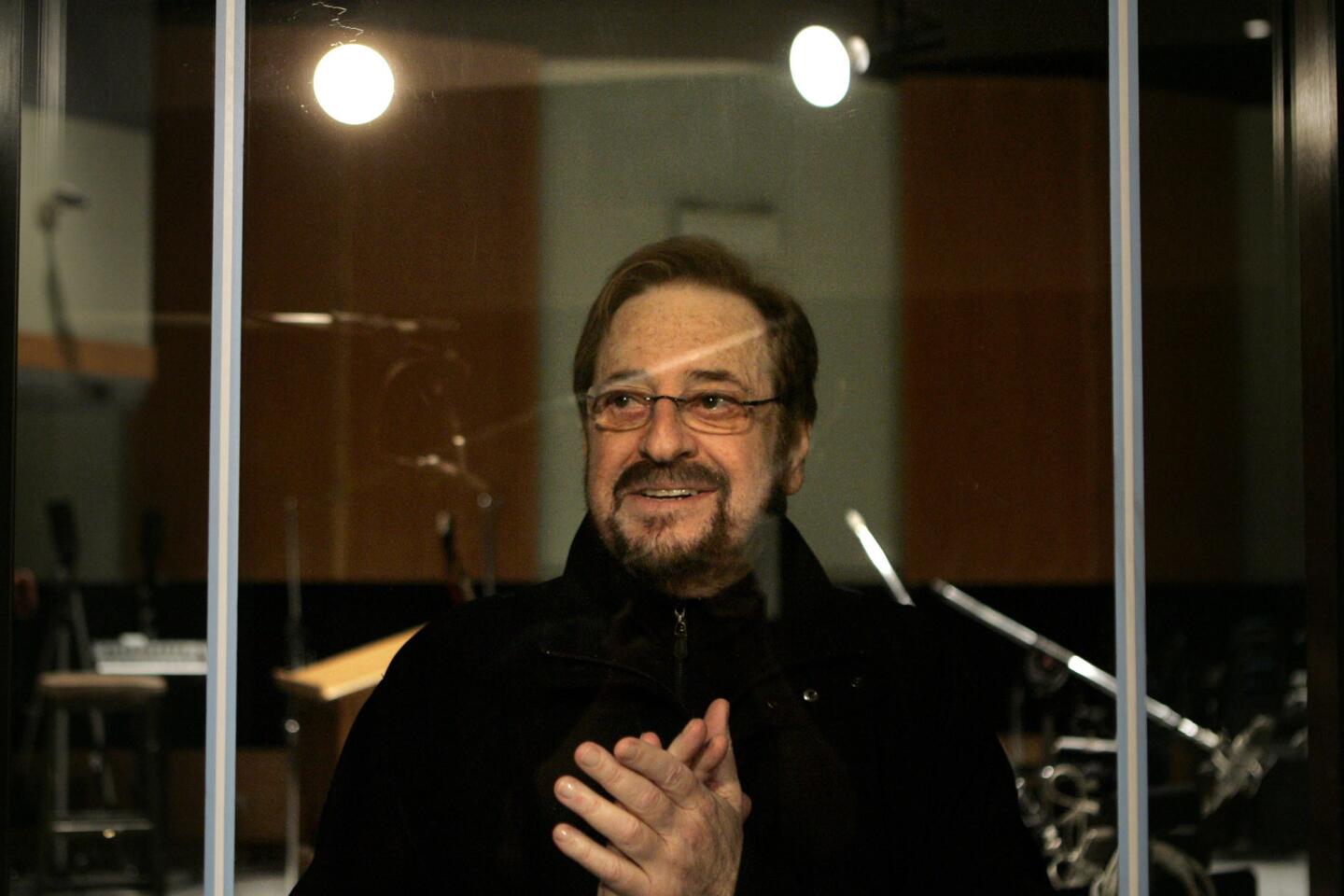

George Aratani dies at 95; L.A. philanthropist who funded Japanese American causes

- Share via

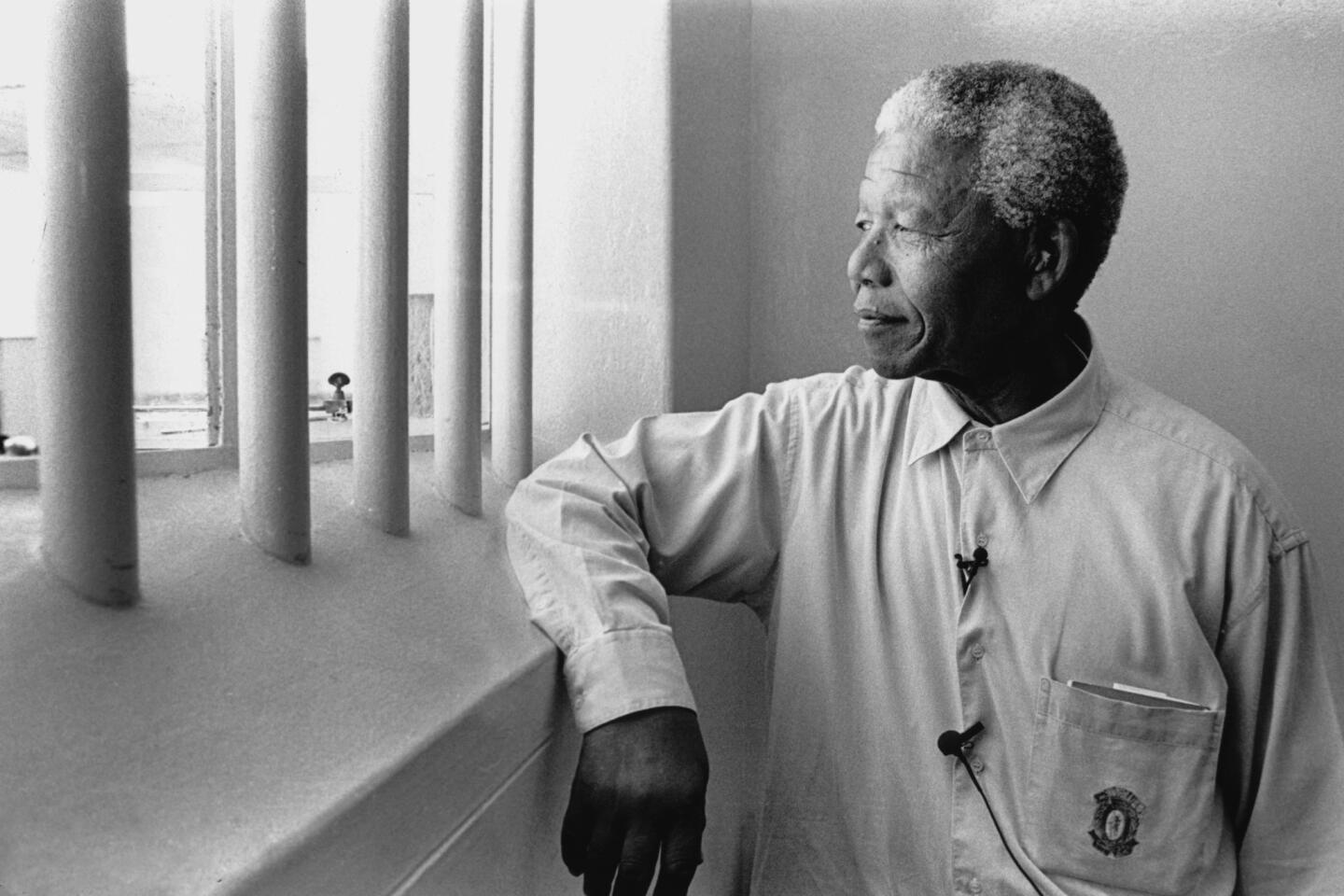

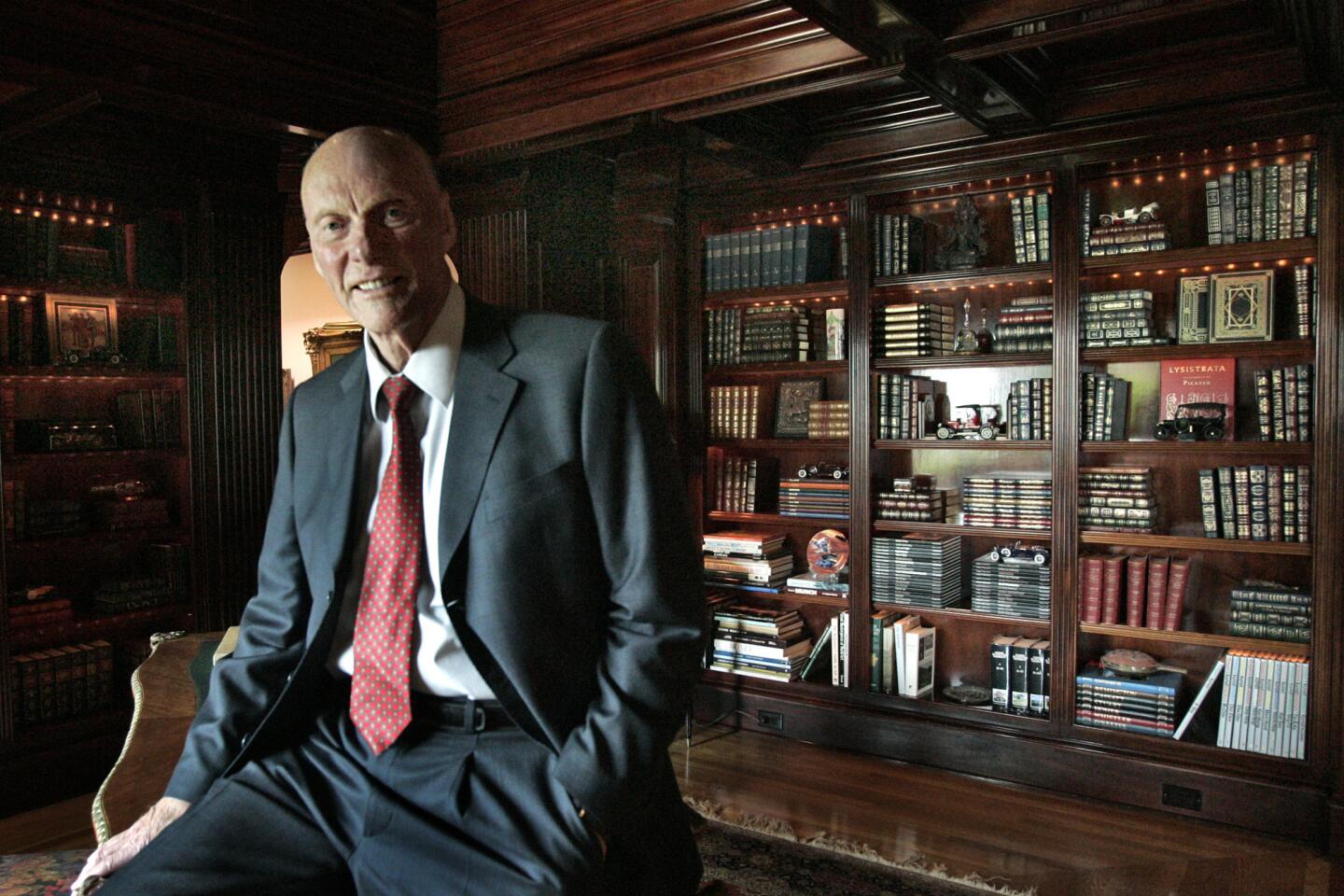

George Aratani, a Los Angeles businessman who donated millions of dollars to Japanese American causes, and with his wife endowed the nation’s first academic chair to study the World War II internment of people of Japanese descent and their efforts to gain redress, has died. He was 95.

An entrepreneur who founded the Mikasa china and Kenwood electronics firms, Aratani died Tuesday at Santa Monica-UCLA Medical Center of complications of pneumonia, his daughter Linda Aratani said. He had lived at the Keiro nursing facility in Lincoln Heights since last summer.

For years, Aratani was among the nation’s most generous contributors to Japanese American educational and cultural causes, especially in Southern California. He and his wife, Sakaye, helped sustain Japanese American cultural centers and museums, retirement homes and sports programs. They have donated to Japanese American religious institutions and supported politicians of Japanese descent, both Democrats and Republicans.

“I like to see Japanese Americans get to Washington, even if I don’t believe in their philosophy,” George Aratani told The Times in 2004.

The couple, longtime supporters of the Asian American and East Asian studies programs at UCLA, gave $500,000 to UCLA in 2004 to establish the first endowed chair to study the wartime relocation and detainment of 120,000 Japanese Americans at U.S. internment camps, and the postwar efforts to redress the injustice.

Aratani and his wife were interned, along with their extended families.

The unprecedented internment was authorized when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 to remove all Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals from the West Coast after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

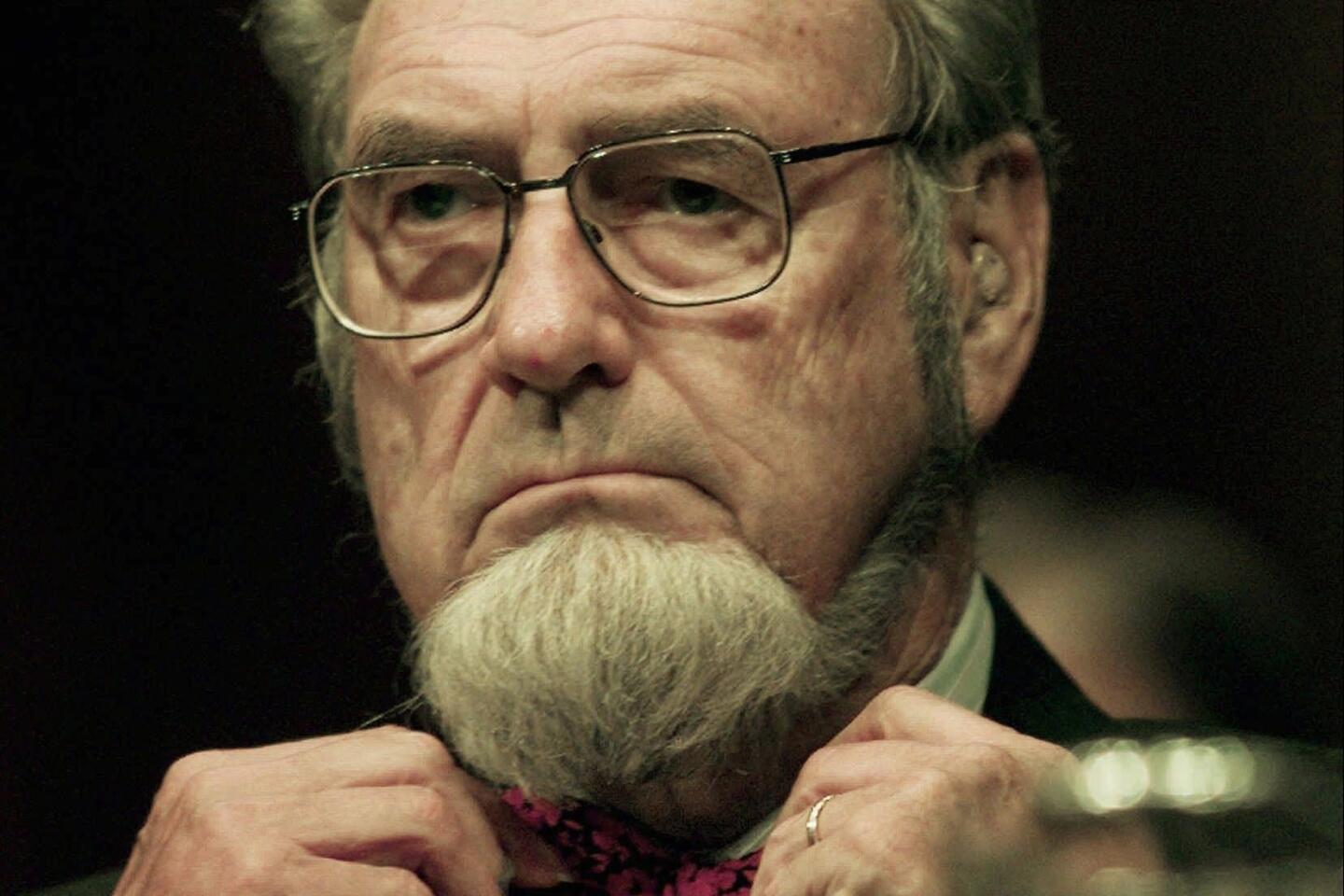

In 1982, a national commission concluded that the internment had been prompted by wartime hysteria and fear. Six years later, President Reagan issued a historic apology, and Congress authorized reparations payments of $20,000 to each former internee.

“Japanese Americans suffered terribly with the forced evacuation, and a guy like me, fortunate enough to have succeeded in business, should help keep the memories alive,” Aratani said in the 2004 interview.

“He felt this very, very special obligation to help the Japanese American community...,” said Don T. Nakanishi, a retired UCLA professor and former director of the university’s Asian American Studies Center, which houses the chair. “He felt very strongly that the story of what the Japanese Americans had experienced continued to be told.”

George Tetsuo Aratani was born May 22, 1917, in Gardena, the only child of Setsuo and Yoshiko Aratani, who had both emigrated from Japan. The young family soon moved to the seaside town of Guadalupe near Santa Maria, where Setsuo Aratani overcame racist land laws to become a successful produce farmer and entrepreneur, with interests that extended to hog farming, chemical fertilizers and large-scale shipping and distribution of farm products.

When it came time for college, young George hoped to enroll at Stanford University, but his father, a native of Hiroshima, asked him to study in Japan, in order to learn the culture and language. Living with his grandmother, he worked on his language skills for 10 months, then enrolled at Tokyo’s prestigious Keio University, where he studied political science for two years.

His mother died while he was in Japan and his father remarried. When his father also became seriously ill, Aratani returned home, then enrolled at Stanford as a junior in 1940. His father died a short time later, and Aratani left school to take over the family business.

The next year, he and his stepmother, Masuko, were forced under Executive Order 9066 to evacuate, leaving their business in the hands of non-Japanese associates — the owners of an ice company with whom the Aratanis did business — and they ended up losing most of it.

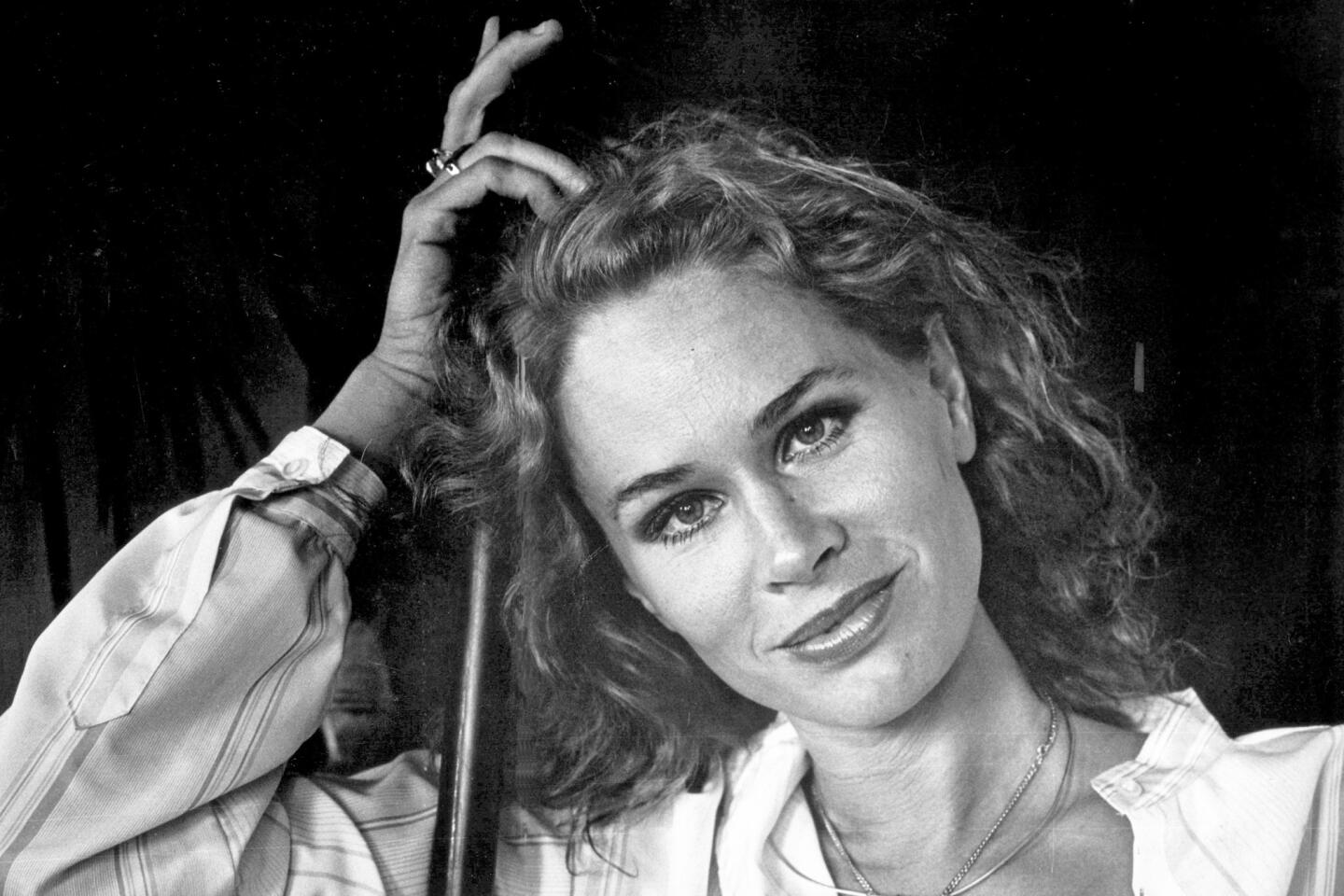

The Aratanis were sent to the Gila River camp in Arizona. Sakaye Inouye, who had met George Aratani through friends before the war, was relocated with her family to the Poston camp, also in Arizona. The two camps, about 100 miles apart, shared medical facilities and when Sakaye needed dental work, she was taken to Gila, where she and George were reacquainted, she told The Times in 1981.

Because Aratani was bilingual, he was allowed to leave the camp to serve in the Army’s Military Intelligence Service, where he taught the Japanese language to American soldiers. On his way to the Army base in Minnesota where he would serve, he stopped at Poston to ask Sakaye to marry him. The two were married in Minneapolis in 1944 and later made their home in Hollywood.

In addition to his daughter Linda, Aratani is survived by his wife of 68 years, Sakaye; and another daughter, Donna Kwee; seven grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

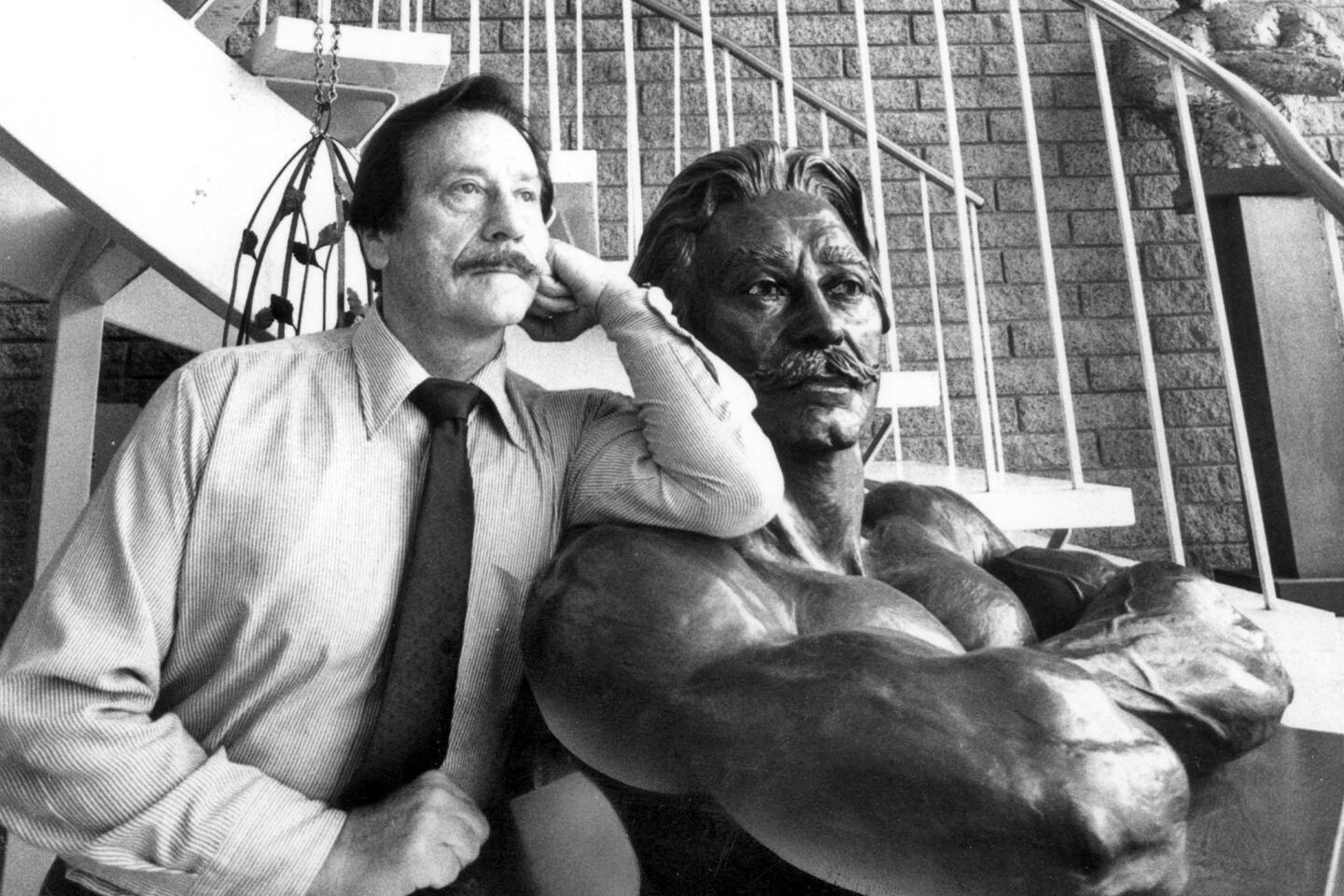

After the war, Aratani started Mikasa, which imported Japanese-made china and ceramics to the U.S., and the electronics firm Kenwood, as well as a third business, which exported U.S. medical equipment to Japan.

After retiring from all three companies, Aratani spent the last years of his life involved in an array of philanthropic activities. In 2004, he estimated that he had given $10 million to a handful of institutions, including the Japanese American National Museum, Japanese American Cultural & Community Center, Keiro Senior HealthCare and UCLA’s Asian American and East Asian studies programs.

“Any organization that needed a donation, needed a sponsorship or just needed a piece of electronics for a raffle, the first name that would pop up was Aratani’s,” said Bill Watanabe, longtime former director of the Little Tokyo Service Center who is now interim director of the cultural and community center.

“I can’t think of an organization he probably didn’t help.”

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. March 2 at the Aratani/Japan America Theatre at the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center, 244 S. San Pedro St. in Little Tokyo.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.