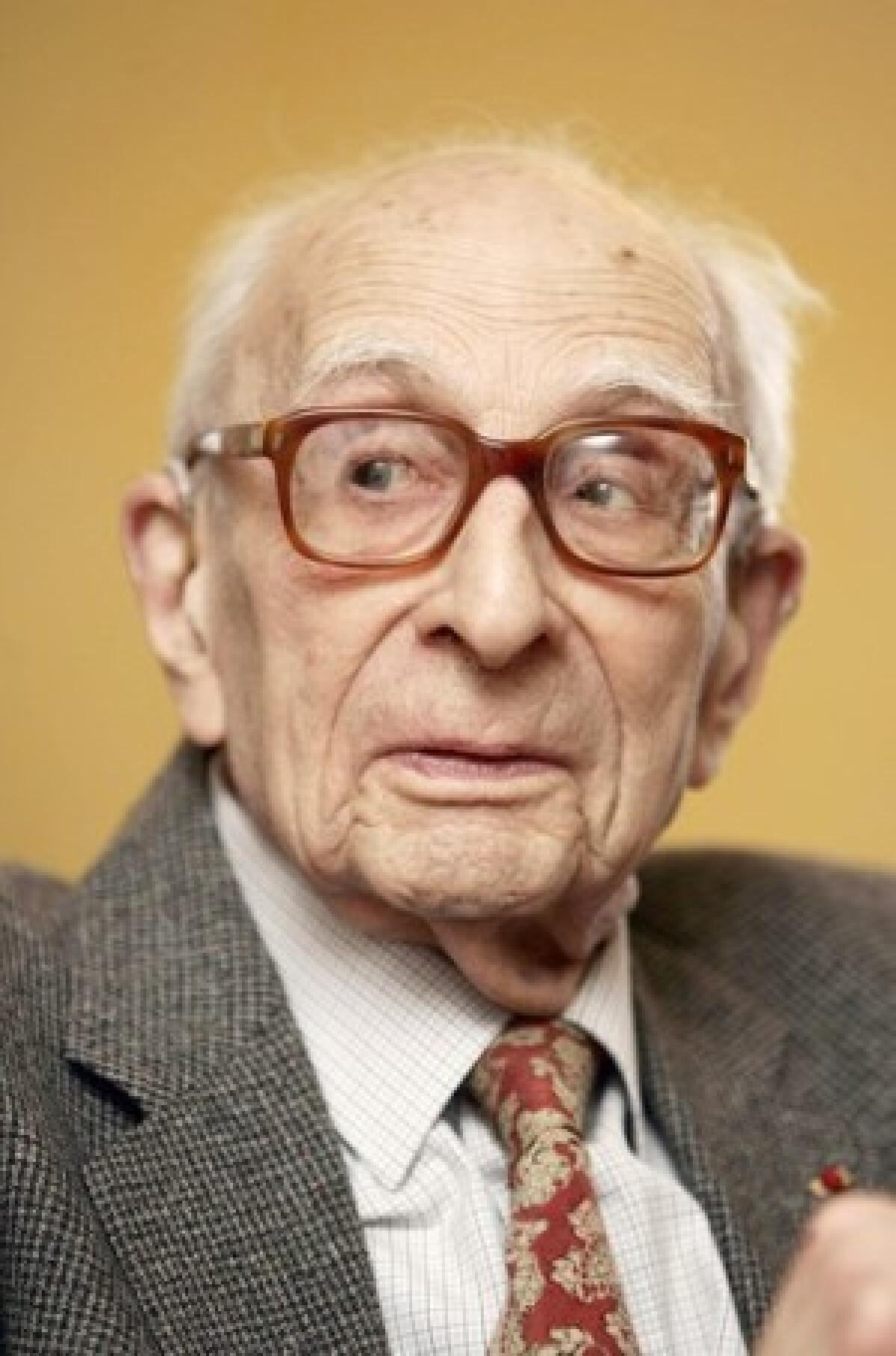

Claude Levi-Strauss dies at 100; French philosopher’s ideas transformed anthropology

- Share via

Claude Levi-Strauss, the French philosopher widely considered the father of modern anthropology because of his then-revolutionary conclusion that so-called primitive societies did not differ greatly intellectually from modern ones, died Friday at his home in Paris from natural causes. He was 100.

Part philosopher, part sociologist and entirely humanist, he studied tribes in Brazil and North America, concluding that virtually all societies shared powerful commonalities of behavior and thought, often expressing them in myths. Towering over the French intellectual scene in the 1960s and 1970s, he founded the school of thought known as structuralism, which holds that common features exist within the enormous varieties of human experience. Those commonalities are rooted partly in nature and partly in the human brain itself.

He concluded that primitive peoples were no less intelligent than “Western” civilizations and that their intelligence could be revealed through their myths and other cultural keystones. Those myths, he argued, all tend to provide answers to such universal questions as “Who are we?” and “How did we come to be in this time and place?”

His studies of American cultures, he said, was “an attempt to show that there are laws of mythical thinking as strict and rigorous as you would find in the natural sciences.”

He was particularly intrigued with opposites, such as black and white, cooked and raw, roasted and boiled, or rational and emotional, that often serve as organizing elements in societies. He explored these binary concepts to find fundamental truths about humanity, noting, for example, that some cannibal groups boiled their friends, but roasted their enemies.

His conclusions about the role of mythology were elegantly expanded in a series of books that included “Tristes Tropiques,” “The Savage Mind” and “Mythologiques.” The jury for France’s most prestigious literary prize, the Prix Goncourt, said it would have awarded the 1955 prize to “Tristes Tropiques” had it been fiction. Novelist and intellectual Susan Sontag called it “one of the great books of the century.”

In the book, the New York Times Book Review said, Levi-Strauss “transformed an expedition to the virgin interiors of the Amazon into a vision quest, and turned anthropology into a spiritual mission to defend mankind against itself.”

Levi-Strauss was especially well-regarded in France, where he was considered a cultural treasure, and accolades quickly began appearing on blogs. French President Nicolas Sarkozy called him an “indefatigable humanist,” while Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner said France had lost a “visionary.”

UNESCO Director-General Koichiro Matsuura called him “one of the giants of the 20th century.” Matsuura said Levi-Strauss’ thought changed the way people perceived each other, striking down such divisive concepts as race and opening the way for a new vision based on recognition of the common bond of humanity.

Claude Levi-Strauss was born Nov. 28, 1908, in Brussels, the son of a painter and the great-grandson of violinist Isaac Strauss. He was reared in Paris and studied law and philosophy at the Sorbonne, earning a degree in philosophy in 1931. After four years of teaching in a secondary school, he accepted an offer to be part of a cultural mission to Brazil, serving as a visiting professor at the newly created University of São Paulo.

During his four years there, he made the first of his many visits into the Amazon interior, living among various tribes and cementing his reputation as an anthropologist. Although popular thought at the time alternately viewed such groups as savages and romanticized them as being unusually close to nature, he considered them merely “societies without writing.”

He returned to France in 1939 to participate in the war effort and was drafted into the army, serving as a liaison to British troops. In “Tristes Tropiques,” he recounted his “disorderly retreat” from the Maginot line after Hitler’s invasion. After France capitulated in 1940, he gained employment at a school in Montpellier, but was soon fired because he was Jewish.

In 1941, he was offered a position at the New School for Social Research in New York, and made his way there via a roundabout boat trip through South America and Puerto Rico. There, he rubbed elbows with American and emigre intellectuals, spent massive amounts of time reading in the New York Public Library and established a sort of university in exile for French academics. Many ideas he picked up there eventually appeared in his books.

After the war, he spent a year as a cultural attache in the French Embassy in Washington so he could continue his studies in the States, then returned to his homeland to complete them, earning his doctorate in anthropology at the University of Paris in 1948. He spent two years at the Musee de l’Homme before joining the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, where a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation allowed him to create a department of economic and social sciences. He also was a professor at the College de France until his retirement in 1982.

By the mid-1960s, he had become a leading influence in France. Sontag wrote in 1963 that “hardly a month passes in France without a major article in some serious literary journal, or an important public lecture, extolling or attacking the ideas of Levi-Strauss.”

By the 1980s, however, his ideas were being supplanted by those of the so-called post-structuralists, who argued that history and experience were far more important than universal laws in shaping human consciousness. More recently, however, the pendulum of thought has been swinging in the opposite direction and his ideas are once more gaining preeminence.

An ardent collector of antiquities, he also was a skilled handyman who touted the virtues of manual labor. He repeatedly lost many of his antiquities, first to seizures by the Nazis and later in two divorces.

Survivors include his third wife, the former Monique Roman; and two sons, Matthieu and Laurent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.