Ebola suits keep wearers safe if all rules are followed, experts say

- Share via

The suit is the difference between life and death.

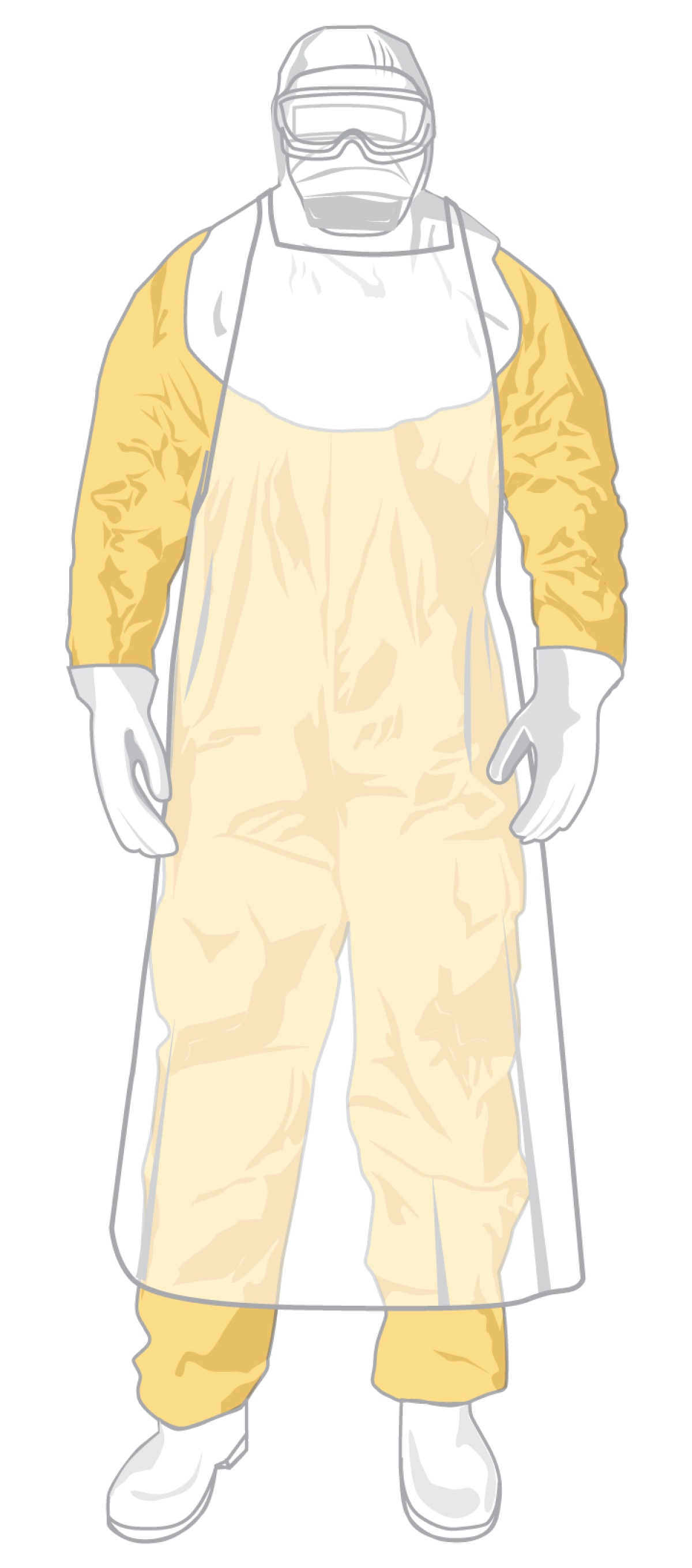

In the heart of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, healthcare workers are sealed head to foot in waterproof suits that have been tested against viral, bacterial and chemical intrusion. Goggles, face masks and double gloves complete the fortress against infection.

But for all the safeguards, the suit has one glaring weakness: the wearer.

The greatest risk comes when the suit is removed in a choreographed series of steps. One deviation from the protocols can lead to contamination.

"I honestly believe you could probably wear a trash bag and be safe," said Dr. William Fischer, a University of North Carolina critical-care specialist who spent several weeks in the West African nation of Guinea this summer treating Ebola patients. "But if you just rip that trash bag off and have fluid flying everywhere you're at risk."

The suit — and the extensive training to use it correctly — lies at the heart of growing concerns from nurses and other healthcare workers that they are being left dangerously vulnerable to the Ebola virus.

They have complained that hospitals are widely unprepared for Ebola patients.

The chaos of handling such an exotic disease was apparent with the arrival of Thomas Eric Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. The Liberian man died last week, and two nurses who cared for him subsequently tested positive for the virus.

Nurses from the hospital said workers who cared for Duncan were given flimsy protective gear and had no proper training in how to use it. The hospital has disputed that, saying the staff was provided with gear that was consistent with federal guidelines "at that time."

Unlike HIV or hepatitis, the Ebola virus is present in every body fluid, including saliva and sweat. Transmission occurs when the virus comes in contact with mucous membranes or broken skin.

The suits used in Africa are sealed against the world.

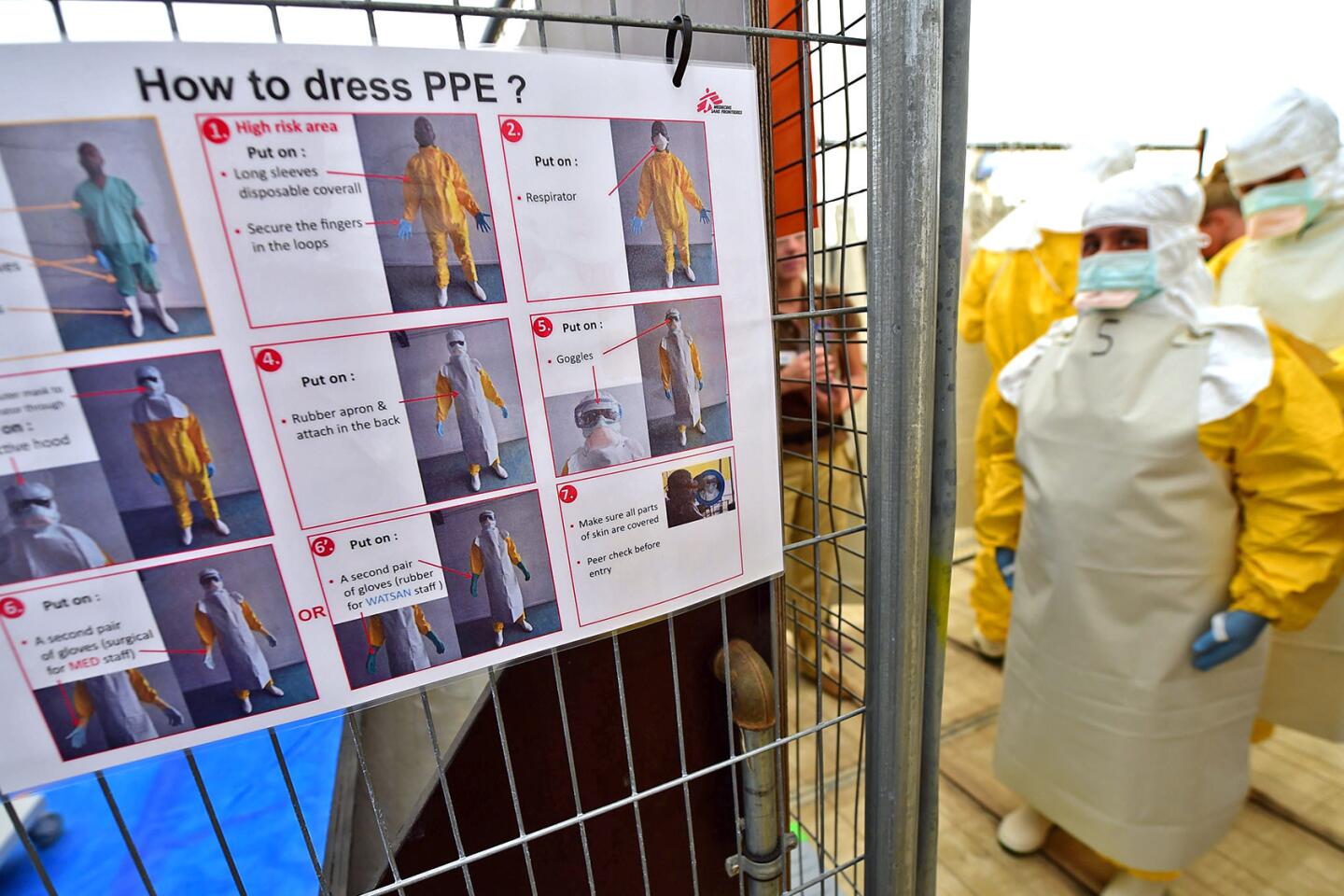

Ebola armor

Protective suits shield healthcare workers from bacteria, viruses and other hazards. Users are most vulnerable to contamination when removing the gear. Click below to see the removal steps used by Doctors Without Borders, which has been responding to Ebola outbreaks in Africa for decades.

Sean Casey, head of the Ebola response team in Liberia for International Medical Corps, said that workers in the African heat sweated profusely in their suits, losing about a quart of water an hour.

"It's incredibly hot," he said in an email from Liberia, where the aid group runs a 70-bed Ebola treatment unit. "People sometimes feel claustrophobic when their masks get soaked in sweat. Some liken it to water boarding."

In the most secure laboratories authorized to handle Ebola for research purposes, scientists breathe only purified air delivered through a hose attached to their hermetically sealed "spacesuits."

To leave the laboratory, they must pass through a chemical shower that lasts several minutes. "It's like being in a car wash," said Thomas Geisbert, an Ebola expert at University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

U.S. hospitals use a wide variety of protective clothing. Infectious disease doctors said that they often faced a trade-off between maximum protection, comfort and functionality.

One common suit, the Tyvek made by Dupont, can sell for as little as $15, without goggles and other accessories.

Until this week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised that all people entering a patient's room wear splash-proof gowns, gloves and eye and face protection. If blood, vomit or feces are present, shoe and leg coverings and double gloves are also suggested.

New guidelines released Tuesday called for a hood that covers the neck and a step-by-step process for gear removal — including multiple hand washings — under the supervision of a site manager.

Suits will be standardized, though the CDC is still deciding whether that standard will be the full-body suits already in use at some larger hospitals.

Nurses from Texas Health Presbyterian said Wednesday that despite months of alerts from the CDC about the possibility of Ebola patients in the United States, their hospital had no clear rules on how to handle a case.

The nurses said some wore gloves with no wrist tape to seal them. Their gowns did not cover their necks from exposure. They wore no protective booties.

Dr. Thomas Frieden, head of the CDC, said this week that after Duncan was diagnosed with Ebola, some workers at Texas Health Presbyterian began wearing three or four layers of gear out of the belief that it was safer. In fact, he said, having to remove more equipment increased the risk of contamination.

Hospitals across the country are assessing their protocols, training and equipment.

"If you're not careful and don't have somebody watching you like a hawk, it's really easy to contaminate yourself," said Dr. Zachary Rubin, who heads infection prevention at UCLA Medical Center.

At his hospital, a team of about 50 emergency department workers are going through drills on how to suit up and remove protective gear. "Every time we go through it, we learn a little bit more," he said.

The best protection is years of practice.

The international aid group Doctors Without Borders has been responding to Ebola outbreaks in Africa for decades. The group's procedures are considered the gold standard — and its safety record backs that up.

At the end of a shift inside a treatment unit, a worker leaves through a special exit and undresses under the direction of a monitor. The process, which starts with the fully suited worker being sprayed with a chlorine disinfectant, involves more than 20 steps.

Remove the outer gloves, the apron, the goggles and hood. Unzip and roll down the coveralls. Remove the inner gloves. Spray the boots, step into the low-risk area and spray them again. Gloved hands are rinsed in the chlorine solution eight times during the process.

Staff members are rotated out of high-risk areas every four weeks to prevent them from becoming complacent.

"We've been doing this for a long time," said Dr. Armand Sprecher, the group's head of public health.

Twitter @AlanZarembo

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.