Fifty years later, looking back at King’s ‘Dream’ speech

Vernon Watkins was there in 1963, when the March on Washington galvanized him to change his life. ‘Have we reached the goals of that day?’ he wonders now.

- Share via

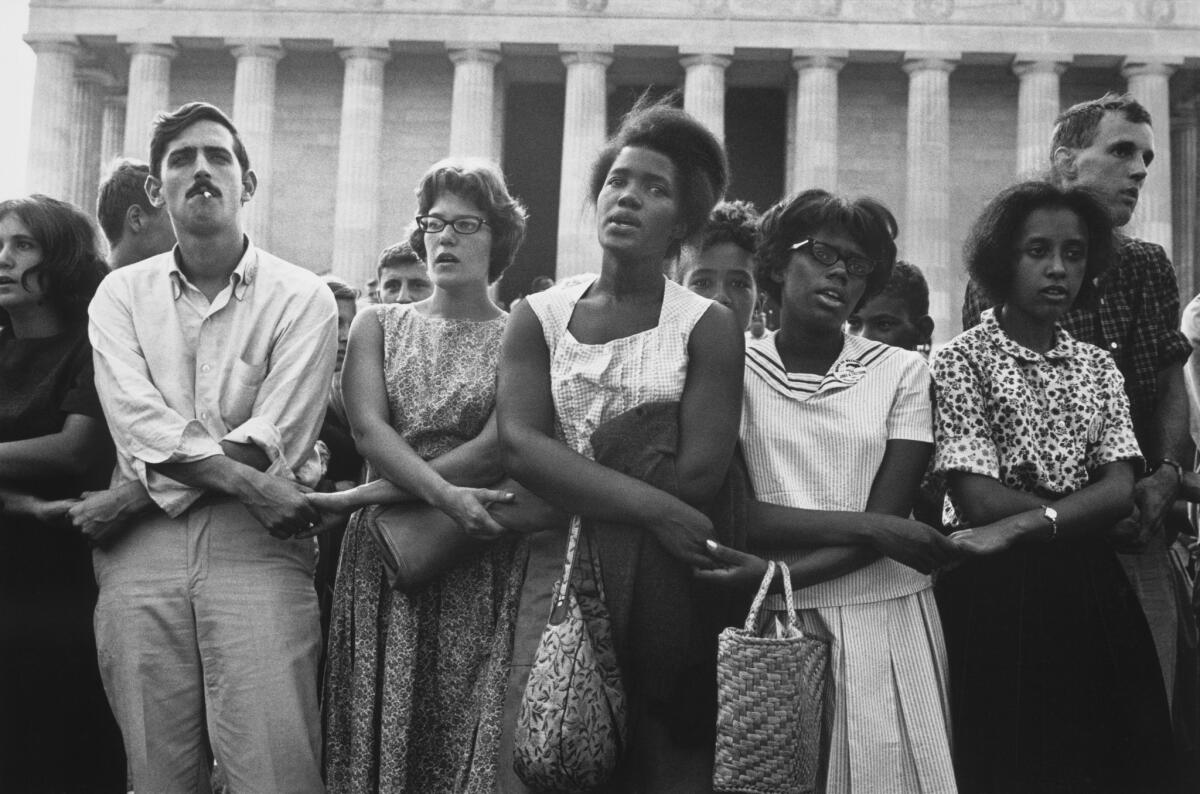

Everywhere Vernon Watkins looked, he saw black, brown and white faces as thousands walked to the Lincoln Memorial. Excitement and tension filled the air. It was half a century ago, and Watkins had come to Washington to demonstrate for jobs and civil rights.

He had been drawn to the March on Washington by the increasingly violent fight over racial equality that divided the nation that summer. The day's most prominent speaker was the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

"I didn't go for the reason most people might think," Watkins pointed out. "I wasn't there to see King."

He was 24 then; young and angry and black. He lived in a segregated Detroit neighborhood. He had a wife and three children, and worked at a printing plant. Getting a good job had tested him. Prospects for his future were uncertain.

"I had one thing on my mind in those days, and that was jobs," he said. "With the way we were treated because of the color of our skin, how was I going to keep providing for my family?"

So he went to Washington, heeding the call of his heroes, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, black labor leaders who were instrumental in organizing the demonstration and whose roles have been obscured by the eloquence of King's "I Have a Dream" speech.

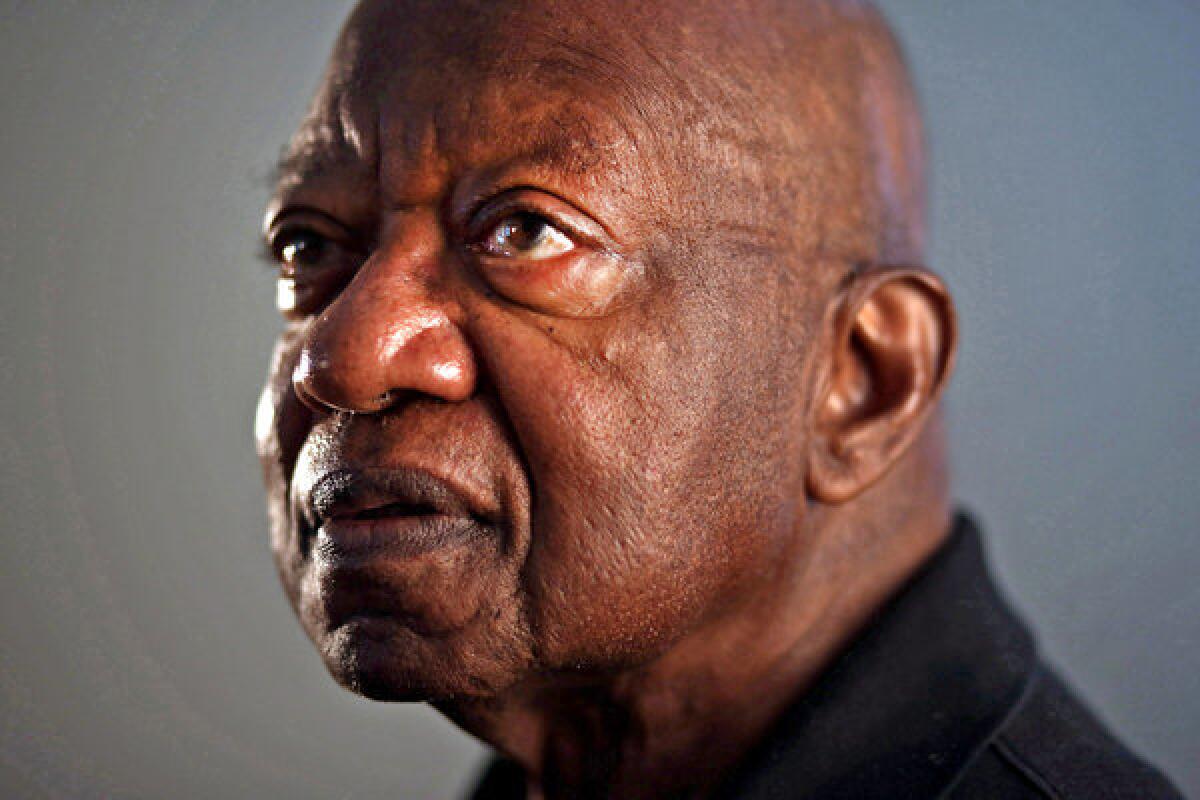

Watkins is retired now, a 74-year-old whose life took an unexpected turn in the years after the march. He moved to Los Angeles, forged a career as one of California's leading union organizers, and became a confidant to politicians including former Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley and congressional leader Nancy Pelosi. He raised his family in middle-class suburbs.

In 2013, have we reached the goals of that day? It's a mixed bag right now. A very mixed bag."— Vernon Watkins

For a long time, the march in 1963 was something he chose not to dwell on. But with the 50th anniversary approaching Aug. 28, he has spent a lot of time sifting through that day's significance.

He brightens, reflecting on how he came away brimming with new confidence, and how much of what was preached from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial has been realized: A growing black middle class. Social acceptance. Easier access to education. The election of a black president.

He becomes downcast as he worries over the country's ongoing racial battles: Voting rights. Income and education disparities. Impoverished urban neighborhoods and steep unemployment among blacks.

"In 2013, have we reached the goals of that day?" he said, running a hand slowly over his bald head. "It's a mixed bag right now. A very mixed bag."

A pivotal moment

Watkins drove to the march with his older brother, steering a green Chevy coupe through the night. Angry whites had been attacking black activists, so Watkins stopped that night only at well-lighted gas stations where he saw other black drivers.

The March on Washington crowd on Aug. 28, 1963, from the top of the Lincoln Memorial. (Associated Press) More photos

He arrived in Washington in the early morning of Aug. 28. He remembers parking and getting lost, and eventually falling in with a group of marchers from New York. They ended up about 200 yards from the podium.

"Looking back," he said, "the sense I have is the wonderment of it all."

The crowd of nearly 200,000 was different than any he had been around. He was expecting white clergy to be there. What he wasn't expecting were the large numbers of white activists who'd come to Washington to support the cause.

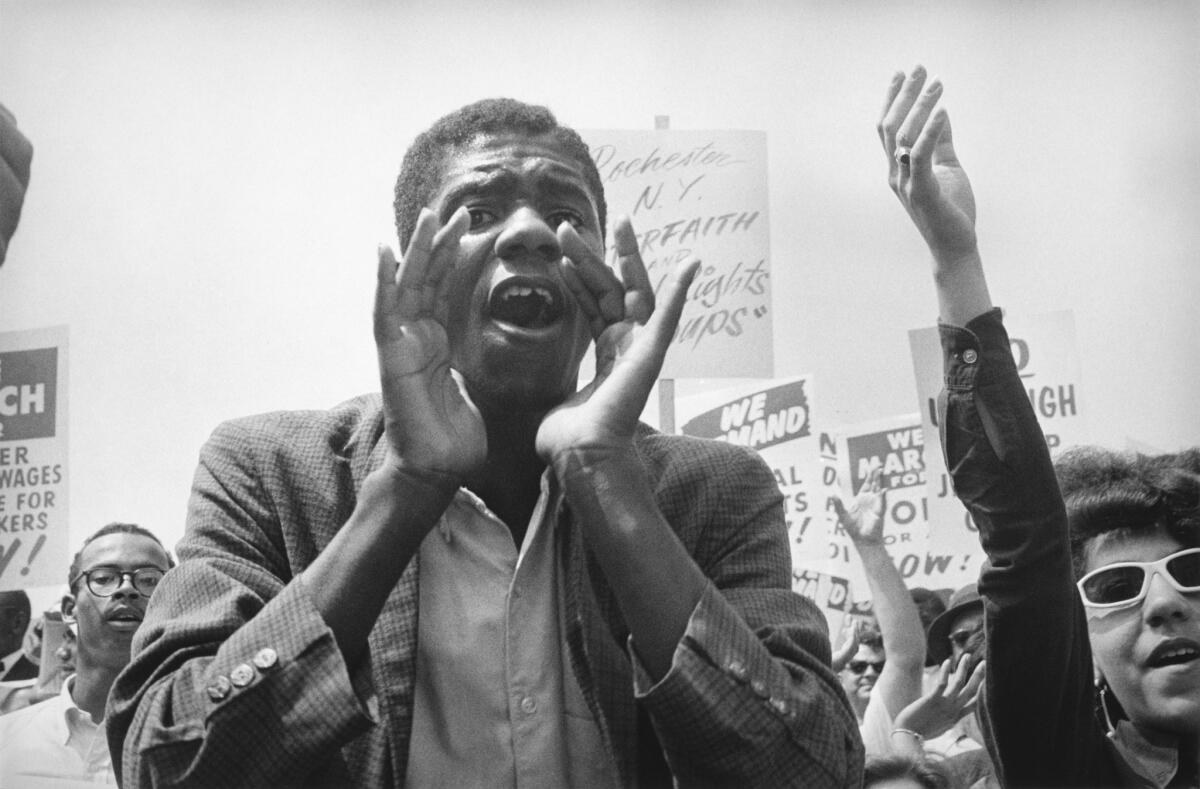

Speakers and musicians took the stage. The public address system hissed with feedback. Many in the crowd were meeting for the first time and swapping stories; Watkins strained to hear the speeches above the din.

"Yes, we want all public accommodations open to all citizens," Randolph told the marchers, "but those accommodations will mean little to those who cannot afford to use them. Yes, we want a Fair Employment Practice Act, but what good will it do if profit-geared automation destroys the jobs of millions of workers, black and white?"

Watkins was captivated by Randolph. "There was a reason they called this the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom," he said, noting the official title.

Like many blacks in 1963, particularly from Northern and Western states, Watkins was skeptical of King and his absolute adherence to nonviolence. It wasn't something that seemed to work in Detroit.

"That 'put your head down' stuff, we didn't really have that mind-set," Watkins says. He and his brother had engaged in long discussions about King, debating the preacher's pacifism, gently poking fun at his Southern speaking style.

"To us," Watkins said, "he was sort of country."

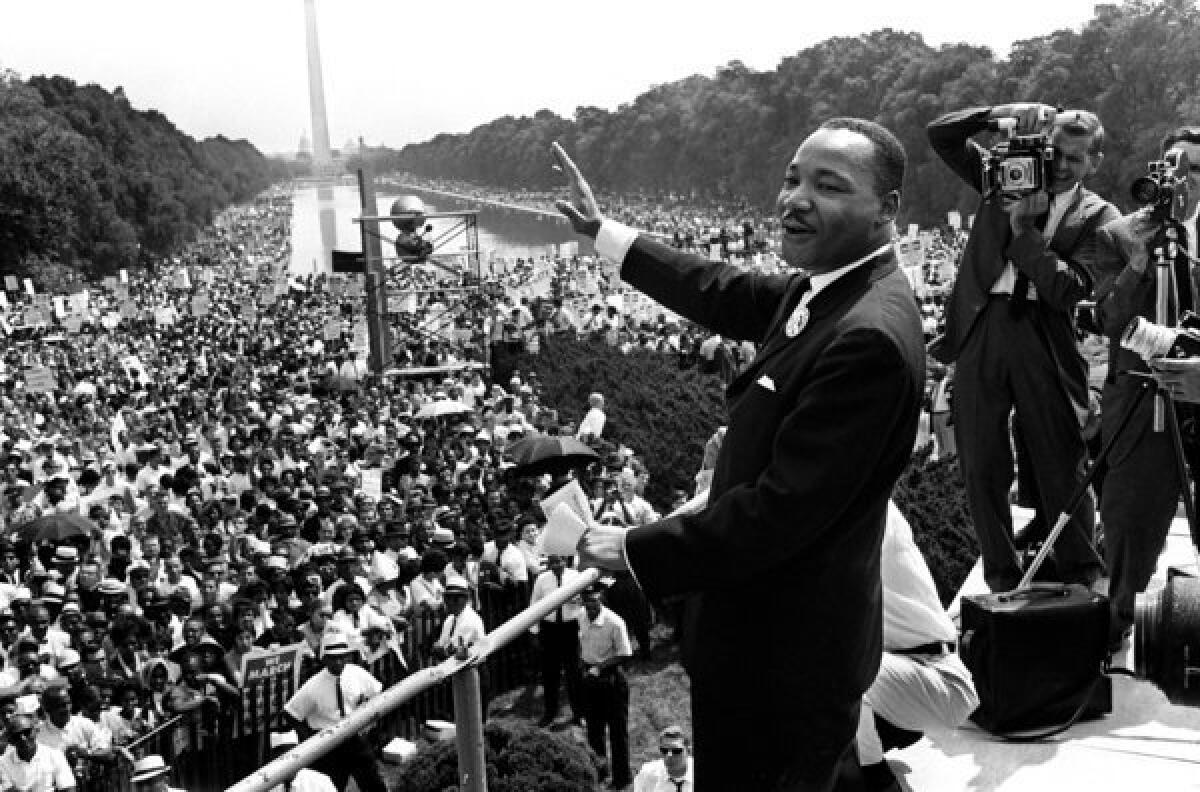

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. waves from the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963. (AFP/Getty Images) More photos

But when King rose to the podium, Watkins was transfixed.

"I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal," King said. "I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.... I have a dream!"

Watkins will never forget the power of King's words.

"He just leaned into the moment," Watkins said. "Looked out at the crowd the way Baptist preachers do and gave them what they needed: that idea of the dream. You might have to wait, but if you fight for dignity, everything is going to be OK."

King prodded him to imagine an America racially unified instead of divided. Still, it was the entire afternoon, taken together, that left the most lasting impression: the camaraderie, the thoughtfulness, the feeling that if a gathering like this could take place, it was time for Watkins to expand his horizons.

He believes that if not for the march he would have remained in Detroit, possibly spending a career in a printing plant in front of a whirring Linotype machine.

"It made me feel better about myself. I came away feeling that I could work to change the questions we were facing: 'What am I going to do for a living? How am I going to survive? What am I going to be?'"

A changed path

Watkins went back to Detroit and soon earned a leadership role in the local printers union. By the late 1960s, he had become an organizer for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees union, working out of its Washington headquarters.

In 1972, he moved to Los Angeles as AFSCME's regional director, leading a small but growing union in California.

Soon he was bargaining for clerical workers who worked for the city of Los Angeles and developing close ties with Bradley, elected in 1973 as the city's first African American mayor. He then focused on University of California campuses, unionizing clerical and blue-collar employees.

"He was at the center of a wave of public sector unionization that changed the landscape in the state," said Kent Wong, director of the UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education. "He was also one who would never let you forget: The battle for jobs and the battle for civil rights are tied together."

Politicians in Los Angeles and across the nation turned to Watkins for advice on winning votes in working-class neighborhoods. His backing, which brought the support of AFSCME, helped solidify liberal gains statewide.

House Democratic leader Pelosi says Watkins has been a trusted advisor for more than 30 years. He stumped for her at San Francisco BART stops during her first run for political office in 1987, and worked with her on several other campaigns.

"He was a movable feast of information," she recalled, noting that in the days before finely tuned digital analysis, few operatives had a better ground-level understanding of what voters were thinking than Watkins did.

A photograph in Vernon Watkins' home shows him with former South African President Nelson Mandela. Watkins attended the March on Washington in 1963, at age 24, and later became one of California's leading union organizers. (Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) More photos

There were setbacks. In the 1980s, Watkins supported Bradley in two unsuccessful campaigns for California governor, and he was a key statewide deputy for Michael S. Dukakis during his failed White House bid.

AFSCME kept growing in California, but labor was losing clout nationally, especially as globalization shut down factories, which had provided blue-collar jobs that allowed minorities to get ahead.

Watkins still endured racial slights, especially on trips for union business outside California. When he went to unionize a Louisiana hospital, a member of the all-white management warned him: "Boy, you better know your place."

Watkins shot from his chair, stood face-to-face with his adversary and cussed him out. "There was no turning the other cheek in that moment," he said.

Images of the past

When Watkins contemplates the last 50 years, he can't help but appreciate how he and his family have achieved King's dream.

He lives in a large three-bedroom house on a hillside in suburban, predominantly white Rancho Cucamonga. Inside, walls are lined with mementos that tell the narrative of his life: portraits of his father, who grew up in rural Alabama; a painting of Los Angeles City Hall, signed by Mayor Bradley; glossy photographs of Watkins beside Nelson Mandela and President Clinton; a note from Michelle Obama.

Looking at the displays recently, he recalled the fear he felt as a child that his future would be limited by race. He thought, too, of how life had unfolded since the march. The influence he held as a labor leader. The people — rich and powerful, poor and dispossessed — he came to help and call friends.

"In 1963," he said, "who could have imagined any of this?"

Sure, we've made a lot of gains. But we thought we would be the ones finishing the job."— Vernon Watkins

Watkins and his wife, Marion, have four children, all college graduates: a financial advisor, a concert promoter, a graphic designer and an executive with a software firm.

There are also 10 grandchildren; the second-youngest is headed to NYU. Watkins speaks of their good fortune and the new opportunities available to minority children born into the middle class.

But he's troubled by the racial inequities that still face the next generation. In the workplace, for example, black unemployment remains more than twice that of whites, as it was 50 years ago.

"In some ways, it's depressing," Watkins said. "You mean to tell me that my grandkids got to face this same stuff, these same issues? Sure, we've made a lot of gains. But we thought we would be the ones finishing the job."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.