Armed standoff in Oregon endures, with more questions than answers

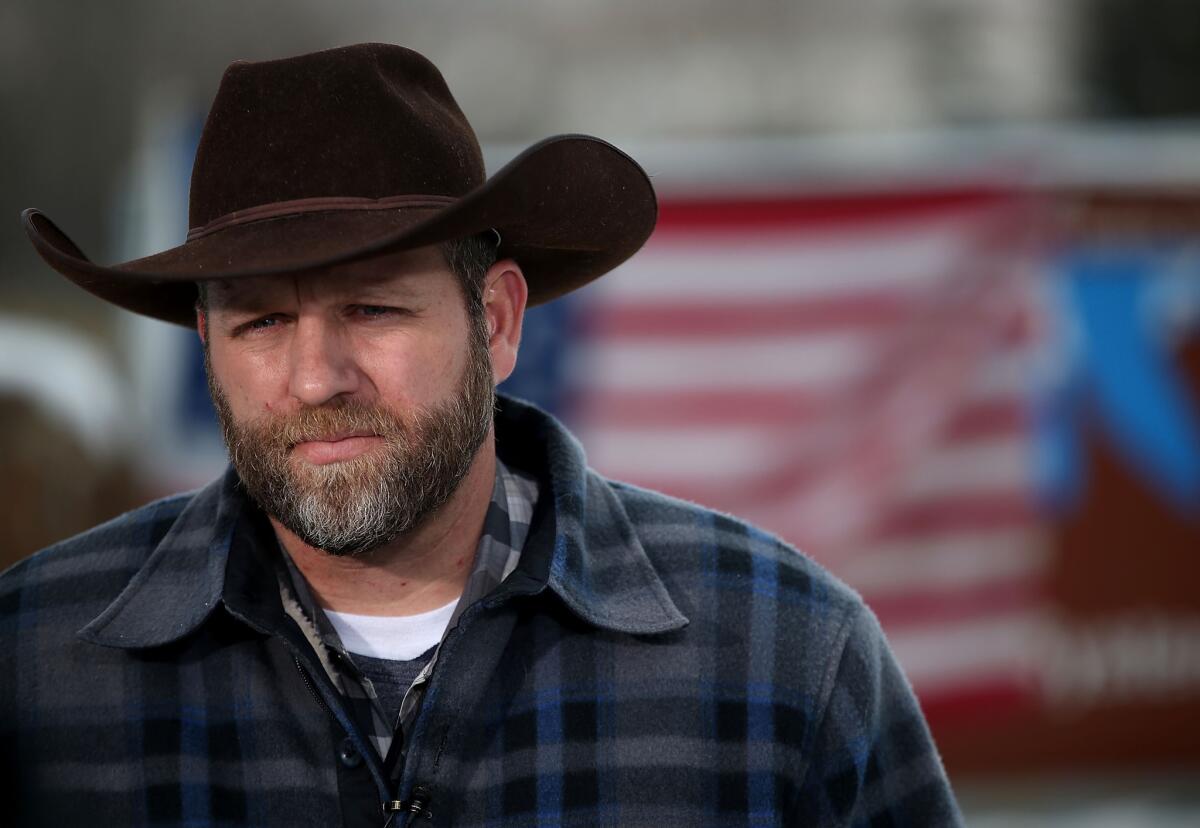

Ammon Bundy, the leader of an anti-government group, talks to reporters at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge near Burns, Ore.

- Share via

Reporting from BURNS, ORE. — When the armed strangers arrived over the weekend at the wildlife reserve in the remote desert outback of southeast Oregon, their leaders said they were prepared to stay for years and die fighting if they must.

But did they mean it? By the next day, protest leader Ammon Bundy seemed to back down a little, suggesting that the men and women holed up at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge headquarters would stand down if the townspeople in Harney County wanted them gone.

Then Bundy emerged again Tuesday and said he and his supporters weren’t going anywhere. “Good things are happening,” he said.

Here in tiny Burns — where some locals have taken hot food to the occupiers, while others have planted street signs imploring them to leave — almost everyone is left to wonder: What do these people want?

A hatchet is buried in a fence at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

Without a clear agenda and no immediate goals beyond challenging federal ownership of vast stretches of land in the West, the occupation has left most of those in this sprawling, lightly populated county wondering whether the media extravaganza that has come to town is going to end in bloodshed or merely a lot more verbal brandishing — and when it is going to end.

On Tuesday, local officials announced that schools, closed since the occupation began Saturday, would reopen Monday. Harney County Sheriff David M. Ward scheduled a community meeting Wednesday to answer townspeople’s questions and signaled that police didn’t intend to wait forever.

“If this goes on any longer, it will have an even greater impact on our tourism and [the] local economy,” he told Oregon Public Broadcasting. “Further attention is what these folks are seeking.”

Ward said the FBI was preparing a criminal case against those occupying several buildings. “The bureau has assured me that those at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge will at some point face charges,” he said.

The occupiers still seem to be saying they won’t leave until they’ve completed their mission. “We will be here as long as needed to secure the land and resources for the people of Harney County,” Ryan Bundy, Ammon Bundy’s brother, said in an interview.

The Bundys’ father, Cliven Bundy, has engaged in a decades-long battle with the federal Bureau of Land Management, which escalated into an armed standoff on his Nevada ranch in 2014.

At a news conference Tuesday, as the activists stood in the snow and took turns addressing the media, Ammon Bundy repeated the group’s goal of returning federal lands to the state and county governments. He ducked questions about the sheriff calling for the activists to leave and did not clarify whether the group intended to occupy more land.

It was left to an Arizona rancher named LaVoy Finicum to explain the only concrete element of their plan disclosed so far: He said the group would search county records to find original land deeds that they believed would show the federal government illegally took private land.

That notion is the only constant among the group’s messages so far — their determination to take land from the federal government and turn it over to the state of Oregon and Harney County. At the crux of their argument is a legal theory that has propelled the so-called land transfer movement.

The occupied Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

The argument hinges on the “enabling acts” that created most states from territories in the West. In exchange, the new states had to cede control of land to the federal government. Transfer movement advocates are focused on one clause that’s standard language in the enabling acts of the states: “until the title thereto shall have been extinguished.”

That phrase alone, they argue, entitles states to reclaim land from the federal government. Courts and legal scholars since the 1930s have rejected this analysis, holding that while these enabling acts allow the federal government to give up its title to the land, they hardly mandate it.

Still, the pitch resounds in rural communities that have watched their economic fortunes tumble — timber towns in Oregon, grazing land in Utah, mining clusters in the Northern Rockies — and which now struggle to pay for basic services including law enforcement, roads and schools.

The idea also tugs at the heartstrings in a place that defines itself by its self-reliance and freedom from government interference.

Finicum, whose Twitter profile features him galloping on horseback with the American flag at his side, underscored those sentiments.

“We want to get the logger back in the forest, get the rancher back to ranching, get the miner back to mining, the farmer back to farming,” Finicum said. “And to jump-start this economy.”

Twitter: @nigelduara

ALSO

How Oregon ranchers unwittingly sparked an armed standoff

Obama announces gun actions, but they illustrate the limits of his office

San Bernardino shooters’ movements after massacre center of FBI probe

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.