What makes a skyscraper the tallest? A ruling is coming

- Share via

NEW YORK — It was all so simple for King Kong, the giant ape who fled his captors by clambering to the top of the Empire State Building.

Back then, there was no question the Manhattan icon was America’s tallest skyscraper.

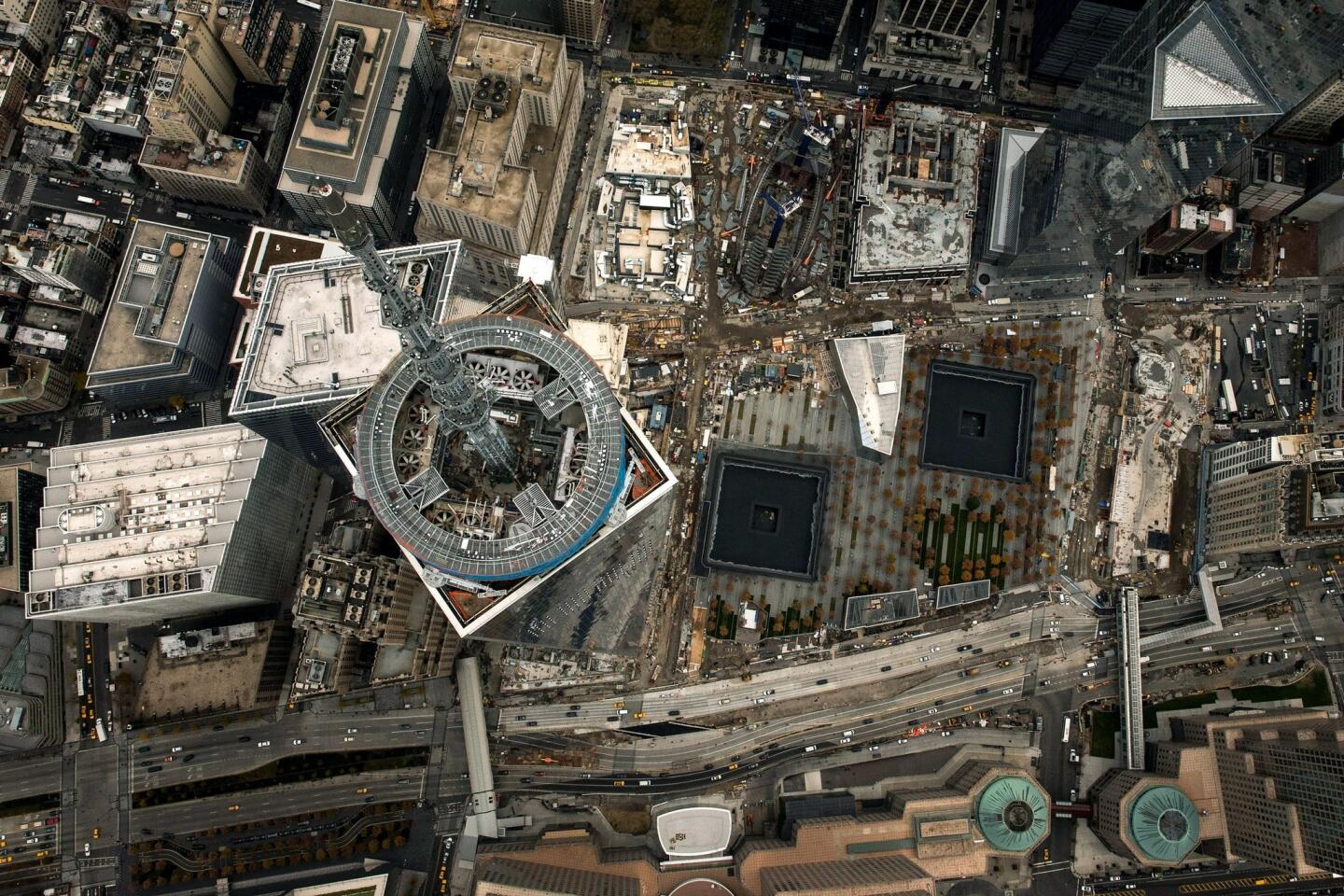

But that was before Sept. 11, 2001, when the destruction of the World Trade Center towers sparked a rebuilding effort that included vows to produce a new “tallest skyscraper” for the country: a 1,776-foot-high building designed to pack a symbolic punch and serve as a memorial to those killed in the attacks.

That was also before spires, antennas and accouterments made it much harder to determine which building could be called the tallest.

Enter the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, which on Tuesday is scheduled to hand down its ruling on the latest tall building issue. Depending on the outcome, the decision could upend building ratings from China to Chicago.

At issue is whether the 408-foot spire and beacon atop One World Trade Center should be considered part of the building’s height. If so, the skyscraper, scheduled to open in Lower Manhattan in 2014, would measure 1,776 feet. Without the spire, it stands 1,368 feet tall — the same height as the original One World Trade Center tower.

If the spire is included, it would bump Chicago’s Willis Tower — formerly the Sears Tower — from the No. 1 U.S. spot. The Chicago building measures 1,729 feet with its antennas and 1,451 feet without them.

None of this would have mattered had the architects of One World Trade Center, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP, not altered the slender, glassy building’s design in 2012 to remove material that would have enclosed the spire and made it indisputably part of the building. The redesign shaved millions of dollars in construction costs and ensured easier maintenance of the spire.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owns the land on which the building sits, and the architects say the multi-tiered spire is more than a communications antenna because it features a beacon with 288 50-watt LED modules and will emit a light visible for 50 miles on a clear night.

To underscore its argument that the spire is no mere ornament, the Port Authority tested the beacon Friday night, and it heralded the spire’s ceremonial placement atop the skyscraper last May. “With the final section of spire now in place, One World Trade Center stands as the Western Hemisphere’s tallest icon of freedom, resilience and the indomitable American spirit,” Scott Rechler, the Port Authority’s vice chairman, said in a statement at the time.

The spire also made One World Trade Center the third-highest skyscraper in the world, according to the council, after buildings in Dubai, United Arab Emirates and Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Without the spire, One World Trade Center will be in 14th place, behind a structure in Shanghai, according to council lists.

Daniel Safarik of the Chicago-based council said that it was unusual for the group to deliberate this intensely over a decision, but that technology had brought about industry-wide design changes that needed to be monitored.

“Are we valuing our ability to put people or material into the air?” he said of the scrutiny of spires and antennas. “If it’s material, we have to look carefully at what that material is and what it does.”

The council is a nonprofit organization founded in 1969 and staffed by architects, engineers, developers and other building experts to encourage international collaboration on tall-building design and to serve as the world’s acknowledged arbiter of the standards by which high-rises are measured.

Visitors to the Sept. 11 memorial at the World Trade Center site Monday did not seem bothered by the idea that the building they gazed at on the chilly, gray day might not be the nation’s tallest.

“I think more people are going to visit this than the Chicago building because it has more meaning. Height doesn’t really matter,” said Amber Miller, a university student visiting from Connecticut, as a white light blinked atop the spire.

Miller and her friend Samantha Calo disagreed with the notion that the spire might just be ornamental. “It was presumably put there for a reason,” Calo said.

Critics of the height debate include Rick Bell, executive director of the American Institute of Architects New York chapter, who compared the spire to a church steeple.

“You don’t say the steeple isn’t part of the church,” Bell said. “This is, for me, a no-brainer.” He added that antennas today were crucial parts of any high building.

Not everyone is convinced that height should be the most important element in ranking the world’s skyscrapers.

Carol Willis, an architectural historian and founder of the Skyscraper Museum in Manhattan, said by focusing on height, people lost sight of other elements.

“What is a big building? It’s not just a vertical height above the ground,” said Willis, noting that even when the original One World Trade Center tower was displaced as the tallest building by Chicago’s Sears (now Willis) Tower in 1974, it remained the bigger building based on square footage. It was also larger, in terms of square footage, than the new World Trade Center tower, said Willis, adding that the council has stepped into a “sticky situation” by limiting criteria to a few defining features.

The drive to build taller buildings picked up steam in the early 1970s, when an increase in urban living sparked the need for more skyscrapers, but it is not new. In medieval times, the town of San Gimignano in Italy’s Tuscany region became the site of a building frenzy when dozens of then-record-breaking skyscrapers — the highest was 230 feet — were erected.

The Empire State Building, from which King Kong swatted away aircraft before toppling to his death in 1933, was the product of a competition in New York to construct the world’s tallest skyscraper. When it was completed in 1931, it trounced two other new Manhattan buildings vying for the title: the Chrysler Building and the Bank of Manhattan building on Wall Street.

Whatever the outcome of the latest competition, Willis said she was not worried about the effect on New York.

“I think New York has got the biggest and best skyline in the world,” she said, “and that’s not going to change.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.