One way to live forever? A time capsule, a Nevada historian says

- Share via

Reporting from Las Vegas — Dennis McBride’s first time capsule was an amateur affair.

The year was 1966 and he was just 11, a scrawny kid whose family lived outside Las Vegas in suburban Boulder City. His father, a truck driver at the Nevada Test Site, had dug up a backyard cottonwood tree, and the boy decided to bury something in the chasm as a record of himself, proof that he existed.

So he placed a few of his favorite Matchbox cars — a Volkswagen and flatbed truck — beneath an upside-down flower pot and covered his little vault with dirt.

For all he knows, it’s still there.

McBride now heads the Nevada State Museum, a curator and historian for whom time capsules remain relevant and, well, just a boyish blast to plan, plant and retrieve.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

He’s filled time capsules with coins, magazines and personal journal entries. And he’s known the childlike surprise of opening others, always mystified at what’s inside, like a pair of showgirl’s shoes or personal letters intended for some future descendant.

McBride, 60, says these well-provisioned packages of time and space have fascinated mankind for eons — whether it’s the earthly sounds and images of surf, wind, thunder and animals placed aboard the 1970s Voyager spacecraft, jewelry and chariots left in a pharaoh’s tomb, or the age-old castaway’s practice of slipping a note in a bottle and throwing it into the sea.

“Capsules let people in future generations know about us and our time, who we were, what was gong on,” he says. “Maybe it’s egotistical, but many people, including me, don’t like the idea that when they die, it’s over. They want a piece of themselves to live on.”

Not only that, historians like McBride know the types of artifacts that his ilk in generations to come will find useful conversation pieces. A decade ago in Boulder City, he took part in planting a time capsule beneath the large public clock downtown for its opening in future decades.

Rather than settle on newspapers, he wanted something more personal.

So he included pages of his own journal on a controversial construction project of the day, with portrayals of “the behind-the-scenes story that include the not-so-nice antics of local politicians you won’t find in any newspaper account.”

Sure, planting time capsules is fun, but opening them is even better.

This spring, McBride’s museum received a call from Las Vegas city workers with a tip on a mystery.

In 2008, officials had demolished the downtown Campos Building, the first state office complex in southern Nevada, built in 1955 to house agencies such as the Division of Parole and Probation. The building’s cornerstone, which included a cylindrical time capsule, was set aside by demolition workers.

It remained stashed in a warehouse closet until recently, when officials called with a question:

Would McBride and his staff want to open it?

The answer: You bet.

For hours, a team worked like archaeologists, sizing up and finally prying loose the top of a metal cylinder 15 inches long and 5 inches in diameter.

Then they excitedly popped the capsule open, breathing in old newspaper dust, decomposing glue and stale air that signifies the passage of time.

The contents, however, were like a pretty gift-wrapped box at Christmas containing underwear or socks.

In other words, a dud.

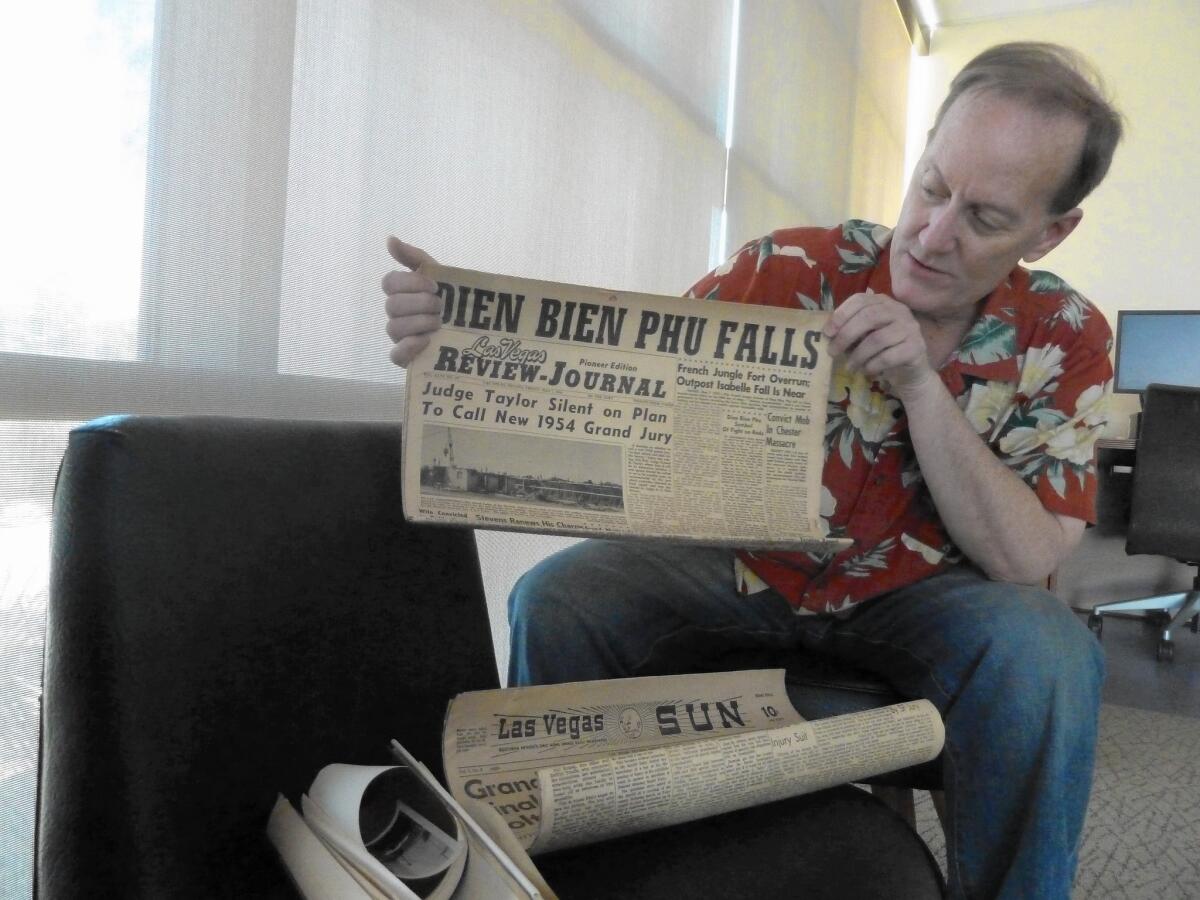

There were the requisite copies of newspapers of the day, the Sun and the Las Vegas Review-Journal, with a May 7, 1954, headline about the French war in Indochina: “Dien Bien Phu Falls: French Jungle Fort Overrun.”

There was also a photograph of Nevada Gov. Charles Russell and various bureaucratic papers.

“No surprises,” McBride says glumly.

This spring, Nevada officials planted another time capsule at McBride’s museum just northeast of downtown Las Vegas. Apparently no lessons were learned from 1954.

The rectangular metal box, placed at the base of a budding ocotillo plant (so officials could find it later) is intended to be opened in time for the state’s 200th birthday in 2064.

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads newsletter >>

Gov. Brian Sandoval contributed an autographed Nevada 150th anniversary commemorative license plate, a photo of him and his family, and a pen he used to sign legislation during his first year in office.

Yawn.

McBride joked that day: “It’s better than bodies.”

So, what would McBride like to see in a future time capsule representing Las Vegas, circa 2015?

For openers, he’d include a package of condoms. (This is Sin City.)

Then, maybe menus from popular restaurants on the Strip, “naughty Vegas toys” from his favorite souvenir shop near the Stratosphere casino, and one of former Mayor Oscar Goodman’s discarded gin bottles.

And if McBride’s no longer alive, maybe his corpse: “Everyone wants to go on forever.”

Twitter: @jglionna

ALSO:

When a Washington fire chief called for help, no one was left

Man pleads guilty to underwater drug-smuggling attempt while wearing scuba gear

Donald Trump says the wall he’ll build on the border could bear his name

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.