Op-Ed: History gives clues to Chief Justice Roberts’ thinking on new Obamacare case

- Share via

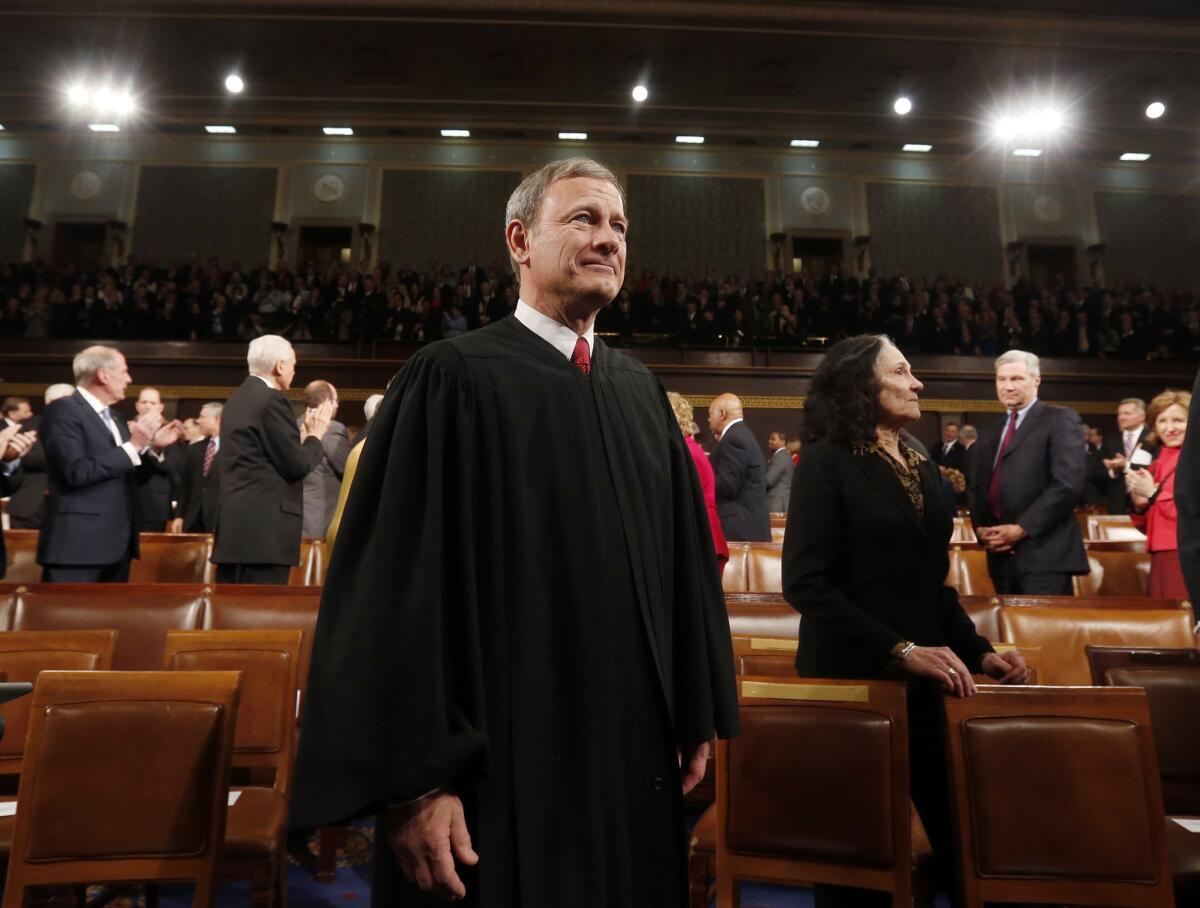

The Supreme Court’s surprising decision last week to hear a new challenge to the Affordable Care Act has once again focused attention on Chief Justice John Roberts, who cast the deciding vote in a 2012 decision that saved Obamacare from being declared unconstitutional. Many court watchers expect that he will once again be the swing vote in deciding a case crucial to the healthcare law, this one involving questions about who qualifies for subsidies under the law. But Roberts’ vote in a recent voting rights case suggests he might not step in to save the health law this time.

At issue in King vs. Burwell is a provision of the Affordable Care Act that authorizes subsidies in the form of tax credits for qualifying individuals who buy their insurance from exchanges “established by the state.” But 34 states did not set up their own healthcare exchanges, opting instead, as the law allows, to send state residents to a federal exchange to buy insurance. The challengers argue that because this exchange was not created by a state, but rather by the federal government, people obtaining insurance through it are not entitled to subsidies.

There are strong reasons to reject this argument. First, the intent of the Affordable Care Act’s drafters is clear. The text as a whole makes sense only if the provision in question is interpreted to include federal exchanges. At worst, the wording of the law might be considered ambiguous, and in ambiguous circumstances the court has said that it should defer to reasonable interpretations by the agency in charge of administering it. In this case, the IRS has interpreted the law to allow subsidies for those on federal exchanges. Finally, the court has a well-established tradition of looking to interpret laws so that they work and are coherent, a practice that long predates a recent tendency on the part of some justices to fixate on narrow snippets of statutory text.

Still, it seems entirely possible that Roberts might focus narrowly this time on the snippet of the act extending subsidies only to those insured by exchanges “established by the state.” One argument he might make in defense of that position is that Congress has the ability to go back and fix any unclear language through a revised statute.

Roberts telegraphed his willingness to take such an approach in the 2013 Shelby County vs. Holder case, which struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. The provision the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional defined which states had to get federal approval (or pre-clearance) before making changes to their voting laws. Roberts’ opinion for the majority ordered the provision struck because it was based on old data. Congress, he reasoned, could simply update the formula to respond to “current conditions” if it wished to.

When Roberts wrote his Shelby County opinion, he knew full well that Congress would not update the coverage formula. Congress is polarized, and the issue was a political hot potato. Indeed, in the period since the opinion, a bill introduced to update the Voting Rights Act has gone nowhere. It is supported by Democrats and a sole Republican, Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.).

Although Congress used to come forward on a bipartisan basis to change laws in response to Supreme Court rulings, the number of such overrides has fallen to a trickle. From 1975 to 1990, Congress overrode an average of 12 Supreme Court decisions in each two-year congressional cycle. In the last decade, that number has fallen to 2.7 every two years, and there have been no significant overrides during the Obama presidency since Republicans took over the House of Representatives. During the last two years, perhaps owing to the intensity of the current political polarization and paralysis, overrides have been even rarer. I have identified just one override, which pertained to a single Indian tribe’s right to certain tribal lands.

Even if Congress were to come together in a bipartisan way to override some statutory interpretations of the Supreme Court, there is no way it is going to override the Supreme Court on the Affordable Care Act. The House has voted dozens of times to repeal the healthcare law in its entirety; there is little chance it would step in now to save a law its members have so long maligned.

Roberts can point to many past cases in which court decisions have initiated a “dialogue” with Congress, which then stepped in with legislation to correct what it saw as errors in the court’s interpretation of congressional statutes.

In today’s fraught political environment, court-Congress dialogues are not generally possible. But that might not stop Roberts from citing the possibility of such a dialogue — especially if what he is really seeking is political cover and a chance to redeem his controversial earlier ruling on the Affordable Care Act with a new one that hobbles a key part of the law.

Richard L. Hasen is a professor of law and politics at the UC Irvine School of Law.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.