Op-Ed: U.S. strategy against Islamic State is too much air, not enough boots

- Share via

Air operations in Iraq and Syria have not stopped the advance of Islamic State. Despite the bombing, the Al Qaeda splinter group has launched a series of offensives in Iraq, gaining new ground in Anbar Province, and it has continued its offensive in Syria.

The desultory bombing mission — far too limited to merit being called an air campaign — has no chance of enabling local allies to eliminate Islamic State sanctuaries. It may not even be enough to keep Islamic State, also known as ISIS, from expanding. After 50 days of obvious failure, it’s time to consider an approach that might work: Get American special forces on the ground with the Sunni Arabs themselves. The only other alternative is to resign ourselves to living with an Al Qaeda state and army.

Islamic State seized the Iraqi city of Mosul on June 10 with a multipronged assault supported by military vehicles. The offensive continued over days, destroying two Iraqi army divisions and driving on Baghdad.

The Iranian military responded at once — reports indicate that Quds Force Commander Qassem Suleimani was in Baghdad with advisors on June 12. Iranian advisors and proxies began flowing into Iraq immediately. The U.S. took no action until Aug. 8, nearly two months later, dropping a small number of bombs aimed at opening a corridor to allow besieged Yazidis to escape from certain death on Mt. Sinjar.

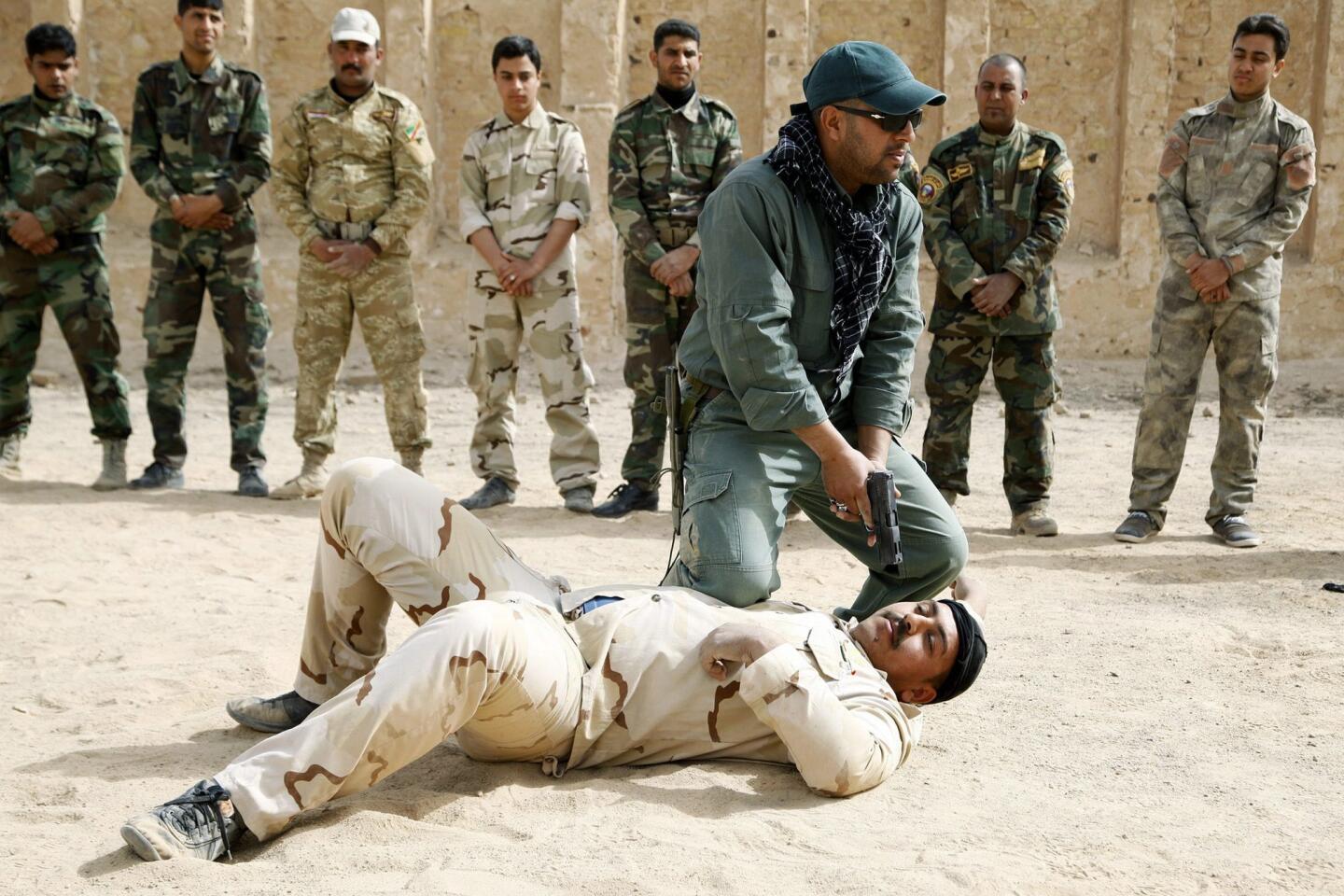

The U.S. has hit about 334 mostly tactical targets in both Syria and Iraq in the intervening 50-odd days. To put that number in perspective, the 76-day air campaign that toppled the Taliban in 2001 dropped 17,500 munitions on Afghanistan. Those bombs directly aided the advance of thousands of Afghan fighters supported by U.S. special operators capable both of advising them and of identifying and designating targets to hit. There are no U.S. special operators on the ground in Iraq or Syria, no pre-planned or prepared advance of Iraqi security forces, and no allies on the ground in Syria. This is not an air campaign.

Islamic State is an adaptable, smart enemy, and its fighters are dispersed through population centers, with an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 of them controlling an area the size of Maryland. Hitting a series of fixed targets such as bases and destroying small concentrations of vehicles will not defeat it. Rather, enabling the air campaign to do meaningful damage to the Islamic State army requires putting some U.S. troops into the Sunni Arab areas that Islamic State now holds. Special forces serving as forward air controllers can direct airstrikes to meaningful targets that are not observable by satellite and overflight.

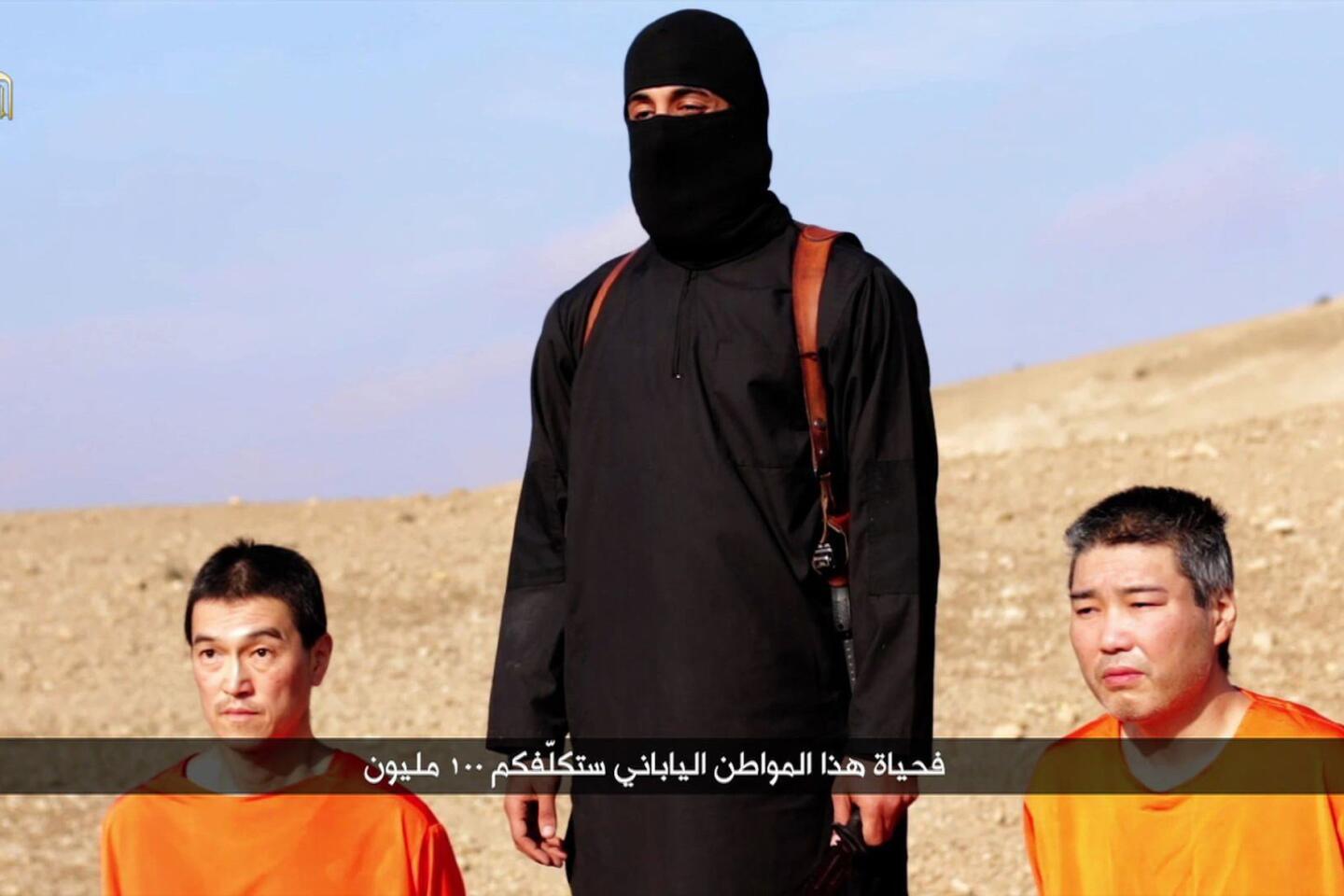

Success against Islamic State requires such deployments for an even more important reason: The Sunni Arabs are essential allies for turning the tide against Islamic State and ousting it from the urban centers it controls.. As long as it can convince or terrify Sunni populations into sheltering its fighters, no amount of air power will defeat the organization. Islamic State terrifies communities by inflicting horrific atrocities on those who resist to deter others from joining them. Communities will only resist, therefore, when they are confident they will win. This makes changing the correlation of forces village by village essential to depriving Islamic State of its sanctuary.

But Islamic State also gains the toleration of Sunni communities that believe they are threatened by something even worse. Bashar Assad’s Alawite-controlled military has used chemical weapons, mass starvation, indiscriminate bombing of civilian areas and denial of drinking water to kill hundreds of thousands of mostly Sunni Syrians. Syria’s Sunnis are unlikely to be eager to fight Islamic State if it seems likely to empower Assad.

Iraq’s Sunnis have not suffered as horribly at the hands of the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad, but they have reason to be extremely suspicious of it. Despite the removal of Nouri Maliki from the premiership, the Iraqi security forces remain commingled with Iranian-backed (and controlled) Shiite militias and riddled with Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps advisors, including people who had previously been helping Assad. Helping the Iraqi security forces is more likely to alienate Iraqi Sunnis than to attract them. U.S. forces need to play the role of honest broker once again, as they did in 2007 and 2008. But they can only play that role if they are present.

The situation in Iraq is very bad, and in Syria it is dire. There is no guarantee that sending American special forces in will turn the tide, while it is certain that they will take casualties. The Obama administration is making an argument for patience that is superficially appealing: Let’s give the air campaign time to work, the Iraqi security forces time to improve and the Syrian opposition time to develop.

The trouble is that the trend lines aren’t going in the right direction. The air campaign is not working, and U.S. efforts to help the Iraqi security forces and train Syrian oppositionists are moving at a glacial pace. Meanwhile, the window of opportunity to work with local Sunni populations against Islamic State grows more likely to close as it continues its campaign of terror and assassination. And U.S. air operations that seem to support Assad’s troops and Iraq’s Shiite militias are already feeding a narrative that America is backing the Iranians and the Shiites against the Arabs and the Sunnis. Allowing that narrative to take deep root could alienate the very people we most need as allies.

Above all, it’s time to recognize that some preferred approaches to the Islamic State problem have been tried and have failed. We tried ignoring the region and counting on the Iraqis and the Syrians to sort things out for themselves. We tried brokering political settlements. We tried targeted strikes to degrade and disrupt terrorist organizations around the world. And now we’ve tried an extremely limited bombing effort for more than 50 days during which the situation has gotten worse. It’s time to try something else.

Frederick W. Kagan is the director of the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute. Kimberly Kagan is the president of the Institute for the Study of War.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.