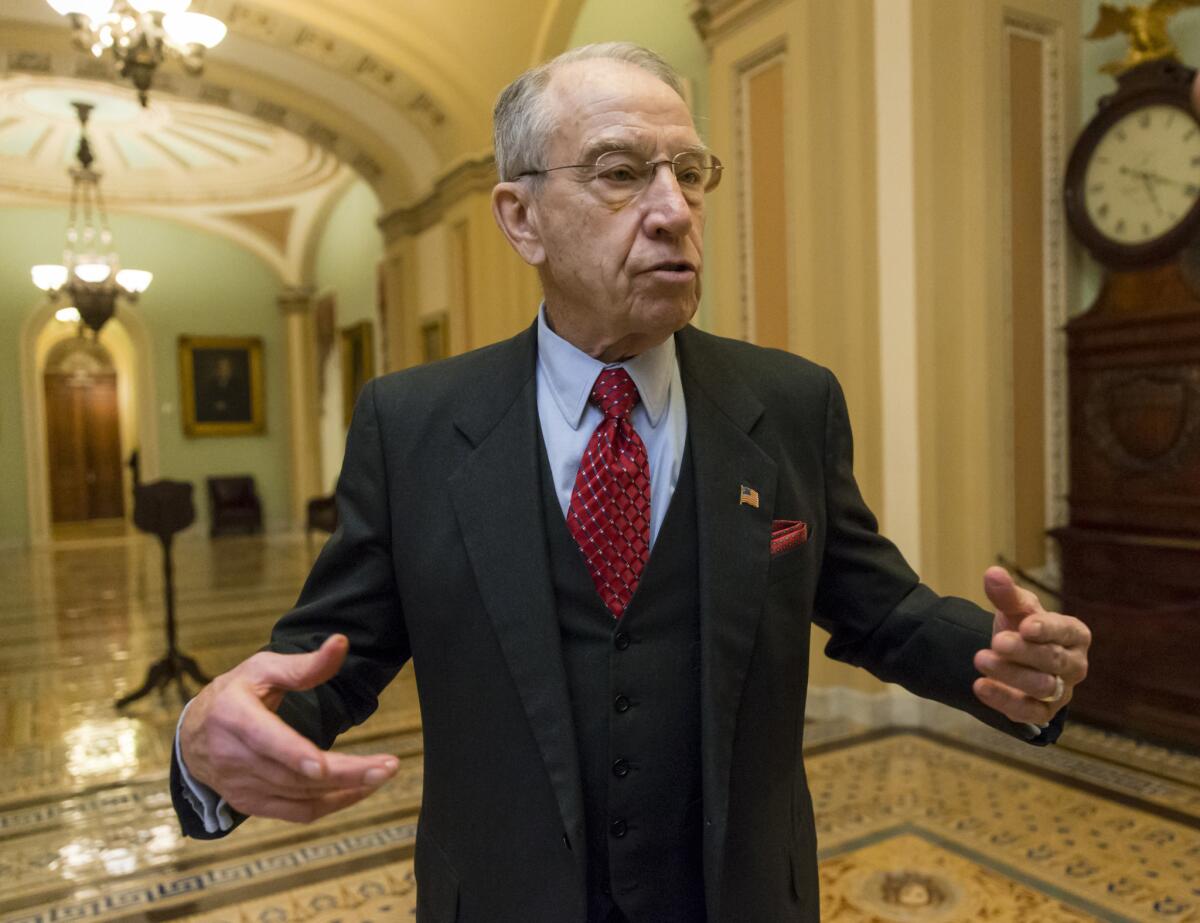

Supreme Court vacancy makes Sen. Charles Grassley the most closely watched Republican in Washington

Sen. Charles E. Grassley of Iowa is chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — As chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Sen. Charles E. Grassley of Iowa would typically be the one to oversee a rigorous inspection of a potential Supreme Court justice.

But with the vacancy on the high court created by the death of Antonin Scalia, it is Grassley who finds himself in a political crucible. He is tasked with enforcing Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s vow that Scalia’s seat will be left vacant until a new president is sworn in — and Grassley’s position at the center of a fight that’s polarizing even by Washington standards has invited heightened scrutiny back home over the impasse and a campaign by Democrats pressuring him to break ranks.

Grassley was unmoved after an hourlong sit-down at the White House.

“Whether everybody in the meeting today wanted to admit it, we all know that considering a nomination in the middle of a heated presidential campaign is bad for the nominee, bad for the court, bad for the process and ultimately bad for the nation,” he said.

The White House and Senate Democrats have singled out Grassley for special attention in part because of comments he made in Iowa recently that they believed showed he might be open to considering a nomination.

On Monday, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid said that “the stakes should even be higher for Sen. Grassley than the other Republican senators,” arguing that his longtime colleague risked tarnishing the reputation of his committee.

“Judiciary chairmen have historically prized their independence and guarded it at all costs from being manhandled for partisan purposes,” Reid said. But with his stance, he argued, Grassley was making the panel “an extension of the [Donald] Trump campaign.”

Reid, who last week repeatedly highlighted critical coverage of Grassley in Iowa news outlets, spoke beside a poster-size version of an editorial headline from the Hawk Eye newspaper in Burlington, Iowa: “History won’t forget this misstep.”

Grassley has been in Washington long enough to recognize the Democrats’ game plan. His aides questioned why President Obama’s initial invitation to discuss the vacancy Tuesday was sent only to their boss and his Democratic counterpart, Sen. Patrick J. Leahy of Vermont. Grassley would attend only if McConnell did as well, a person familiar with the discussions over the meeting said.

In that meeting, Obama offered Grassley the opportunity to suggest potential nominees he might consider acceptable, one he turned down.

“Sen. Grassley and I made it clear that we don’t intend to take up a nominee or to have a hearing,” McConnell told reporters after the meeting.

Still, on the right there is some apprehension about whether Grassley, a former pig farmer and the first nonlawyer to lead the committee, might cave under the pressure.

Bob Vander Plaats, president of the social conservative advocacy group Family Leader and an influential leader of Iowa evangelicals, said he recently spoke with the senator to encourage him “to stay the course.”

“The momentum and the enthusiasm is definitely on the Republican side. Sen. Grassley can see that,” Vander Plaats said in an interview. “If he would go away from a conservative move and say, ‘I would embrace Obama,’ that would put him at risk.”

But Grassley has only doubled down on his stance as pressure from the left mounted. After a meeting between McConnell and the Judiciary Committee’s 11 Republican members, Grassley released a letter from them underlining their plan to exercise their “constitutional authority to withhold consent on any nominee.”

Aides say he is guided not by pressure from party leaders or the conservative base but by his own deep-seated belief that the unexpected election-year vacancy offers the country a rare opportunity for a national debate about the role of the Supreme Court.

“It doesn’t matter how much the minority leader jumps up and down,” Grassley said on the Senate floor. “We aren’t going to let liberals get away with denying the American people an opportunity to be heard.”

To which White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest responded Tuesday: “We had that debate in 2012, and that was a debate that the president won.”

The normally accessible Grassley has increasingly avoided questions about the court fight. Last week, he sought out a reporter to discuss the prospect of Puerto Rican bankruptcy rather than speak to other journalists who would have asked about the White House meeting.

Grassley, 82, entered this final year of his sixth term with a seemingly clear path to a seventh. Only a trio of little-known former Democratic state lawmakers has stepped forward to challenge him. But given the competing forces converging on him, other Democrats are giving it serious thought. Former Iowa Gov. Chet Culver, whose father was unseated by Grassley in 1980, and Culver’s former lieutenant governor, Patty Judge, are said to be considering runs.

Grassley’s reelection campaigns have always employed a two-word slogan: “Grassley works.” But Democrats say his position on the Supreme Court fight risks undercutting his reputation.

“People feel like he does his job. Whether you agree with him on the issues or not is another question,” said Andy McGuire, the Iowa Democratic Party chairwoman. “He does appear to be more vulnerable than he was before, because this is really hitting at the core of he who he is.”

Democrats know the odds of electoral retribution are long against Grassley even if the court vacancy has taken a toll in Iowa. So much of their rhetoric, as Reid’s showed, has been designed to target Grassley’s sense of institutionalism and defense of Senate prerogatives.

Grassley is unlikely to give in, said David Yepsen, a longtime political reporter for the Des Moines Register who is now director of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University.

“He cares a great deal about those traditions. So they are really poking him where it hurts,” Yepsen said. “But having staked out his position, he’s not going to buckle under this.”

That doesn’t mean the White House won’t continue trying. On Tuesday, the man who once wielded the same committee gavel Grassley now holds also gave him special attention.

As members of the press corps scrambled to get in position in the Oval Office for a photo op of Tuesday’s meeting, Vice President Joe Biden cautioned a boom mic operator who got too close to Grassley.

“Don’t hurt Sen. Grassley,” Biden said. “We need him.”

For more White House coverage, follow @mikememoli

ALSO

Republicans want to cut government spending? Not these Trump supporters

Why Trump and Sanders are praising healthcare in other countries

Enrollment growth in Obamacare health insurance slower than expected

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.