9/11 suspects may face death penalty

- Share via

MIAMI — The Pentagon announced Monday that it was seeking the death penalty against alleged Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and five other men, in a move that will probably ensure that the controversial military commissions at the Guantanamo Bay prison live on into the next presidential administration.

The murder and conspiracy charges against the six men accused of planning the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon would be the first capital cases against any of the nearly 800 detainees who have been brought to the U.S. military prison in Cuba.

They also marked a change in strategy for the Office of Military Commissions, which for six years has focused on building cases against about a dozen detainees accused of lesser crimes.

As Bush administration policy in Guantanamo comes under sharper scrutiny in this election year, the White House has pressured the commissions to try and convict so-called high-value detainees like Mohammed. That pressure became so intense last year that the chief prosecutor quit in protest of what he considered political interference.

The charges must first be approved by the commissions’ convening authority, former Defense Department Inspector General Susan J. Crawford, but because her office applied pressure to prosecute the high-value detainees, her approval appeared likely.

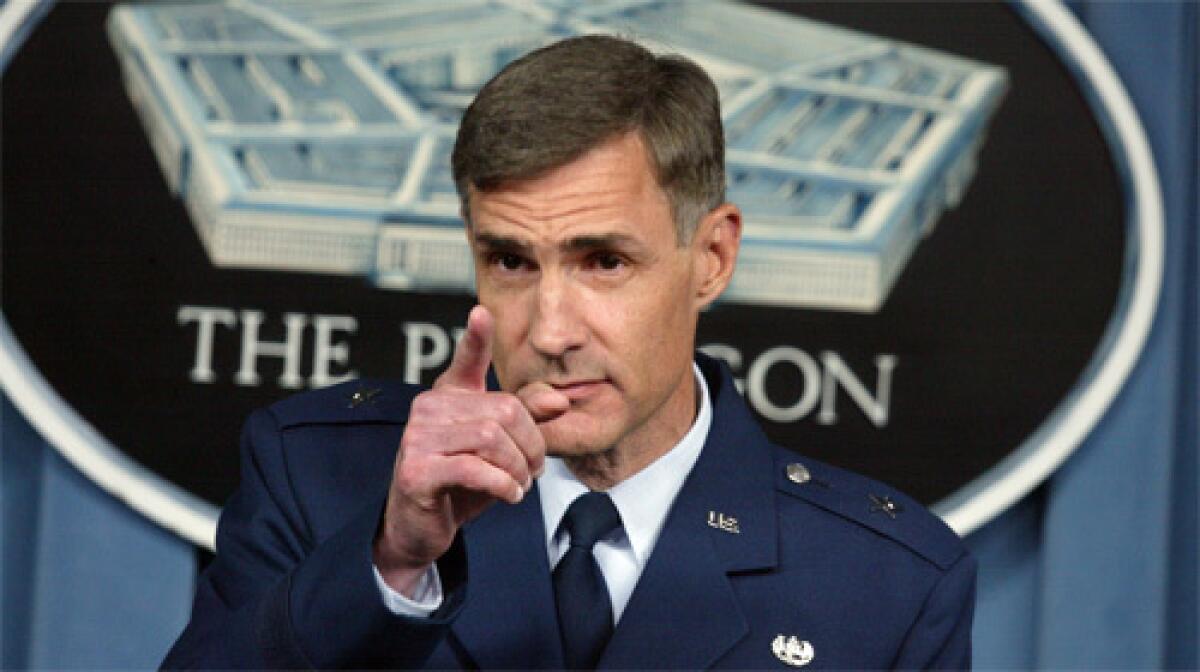

Air Force Brig. Gen. Thomas Hartmann, legal advisor to Crawford and an advocate of the new strategy of making the most heinous suspects a priority for the commissions, said the alleged Sept. 11 conspirators would have nearly identical rights to defendants tried in courts-martial.

Tribunal rules call for the Guantanamo court to arraign defendants within 30 days of their being served charges and for trial to begin within four months. But Hartmann acknowledged that the timing could be pushed back by legal wrangling.

The charges announced Monday are expected to spur fresh challenges to the commissions’ legitimacy and to the admissibility of evidence obtained through such interrogation methods as waterboarding, a simulated drowning technique.

Although the suspects have been in U.S. custody for years, they only become eligible for legal counsel once the charges are approved by Crawford and are served to them at Guantanamo.

The Guantanamo detention network of camps and prisons has neither a death row nor an execution chamber, but those facilities are said to be in the works.

“That’s all still being put together,” said Army Major Robert D. Gifford, spokesman and legal advisor for the commissions.

At least five of the six charged with Sept. 11 roles are being held in isolation at a maximum-security facility at Guantanamo, where three concrete-and-steel prisons and four camps of metal-mesh cells and barracks are arrayed along the rocky shoreline and surrounded by opaque fencing topped with coils of barbed wire.

Also charged along with Mohammed, known among his military jailers as KSM, are: Ramzi Binalshibh, a Yemeni who allegedly provided logistics for the Hamburg terrorist cell; Mohammed Qahtani, known as the 20th hijacker for his alleged thwarted plans to aid fellow Saudis in seizing U.S. aircraft; Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, a nephew of Mohammed who was raised in Kuwait; Mustafa Ahmed Hawsawi, a Saudi who allegedly provided logistic support to KSM and others; and Walid bin Attash, alleged scion of a terrorist family long aligned with Al Qaeda.

Military and civilian legal experts predicted the trials of the six, likely to be conducted jointly, won’t begin until at least fall and may start even beyond the November presidential election.

“The fact is that we’re going to have a military commission for those the United States believes, and most of the world acknowledges, to be ring leaders of the 9/11 attacks,” said Scott Silliman, a Duke University law professor and former military judge advocate. “That should not be delayed simply because we’re in an election year.”

Silliman conceded there are probably political considerations to the timing of the charges but said he doubted the trial would get underway before the election. Military defense attorneys will make challenges on their clients’ behalf and demand access to classified evidence and faraway witnesses, which would probably delay the process, Silliman said.

One of the first defense challenges in the case is likely to be the admissibility of evidence obtained through interrogation methods that the administration approved for Mohammed and others but that human rights groups contend are torture.

The military judge assigned to the trial will make any determinations about admissibility based on provisions of the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 that, by virtue of an amendment attached by former POW and presidential hopeful Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), prohibits the use of “cruel, degrading or inhumane” interrogation practices.

Mohammed’s waterboarding, however, probably occurred before the legislation passed, because he was captured in Pakistan in 2003 and reportedly subjected to the simulated drowning technique in CIA custody shortly thereafter.

In announcing the transfer of Mohammed and 13 other high-value terrorism suspects to Guantanamo in September 2006, President Bush trumpeted the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” as a life-saving weapon in the United States’ arsenal for combating terrorism.

Some observers involved in the fight against terrorism question whether the commissions are a fair forum.

“It’s a stacked deck. I know people who are part of the tribunal process who represent detainees, JAG officers, who will tell you that they are politically to the right of Attila the Hun, and even they will tell you the construct is ridiculous, that it lacks due process,” said Jack Cloonan, a former FBI agent assigned to the Osama bin Laden task force in New York.

Longtime critics of the military commissions deemed Monday’s charges overdue and blamed the delays on the tribunal system itself.

“If the United States wants to build up its moral authority around the world, this is not the way to do so,” said Jennifer Daskal, senior counter-terrorism counsel for Human Rights Watch. “Over the past six years, the federal courts have successfully prosecuted dozens of international terrorists, and that is where these cases belong.”

Kevin Lanigan, director of the law and security program of Human Rights First and a former U.S. Army Reserve judge advocate in Bosnia, Afghanistan and Iraq, blamed the delay in bringing 9/11 suspects to trial on the Bush administration’s efforts to keep the defendants out of the U.S. justice system.

“The administration still refuses to acknowledge its two greatest self-imposed obstacles to achieving justice for the families and victims of 9/11: the absence of a credible and truly independent system for trying these defendants and problems caused by the use of official cruelty in interrogating them,” Lanigan said.

Three other cases are underway at the Guantanamo tribunal, a complex of tents and airfield buildings housing two courtrooms, only one of which has sufficient security for high-value suspects.

Guantanamo received its prisoners in January 2002, but the tribunal has yet to try a case. The only procedure against a detainee that has been completed was a plea bargain in the case of Australian David Hicks, in what was seen as a political favor by Bush to then-Prime Minister John Howard who was under pressure to bring Hicks home during a reelection campaign.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.