Civilian Killings Went Unpunished

- Share via

The men of B Company were in a dangerous state of mind. They had lost five men in a firefight the day before. The morning of Feb. 8, 1968, brought unwelcome orders to resume their sweep of the countryside, a green patchwork of rice paddies along Vietnam’s central coast.

They met no resistance as they entered a nondescript settlement in Quang Nam province. So Jamie Henry, a 20-year-old medic, set his rifle down in a hut, unfastened his bandoliers and lighted a cigarette.

Just then, the voice of a lieutenant crackled across the radio. He reported that he had rounded up 19 civilians, and wanted to know what to do with them. Henry later recalled the company commander’s response:

Kill anything that moves.

Henry stepped outside the hut and saw a small crowd of women and children. Then the shooting began.Moments later, the 19 villagers lay dead or dying.

Back home in California, Henry published an account of the slaughter and held a news conference to air his allegations. Yet he and other Vietnam veterans who spoke out about war crimes were branded traitors and fabricators. No one was ever prosecuted for the massacre.

Now, nearly 40 years later, declassified Army files show that Henry was telling the truth — about the Feb. 8 killings and a series of other atrocities by the men of B Company.

The files are part of a once-secret archive, assembled by a Pentagon task force in the early 1970s, that shows that confirmed atrocities by U.S. forces in Vietnam were more extensive than was previously known.

The documents detail 320 alleged incidents that were substantiated by Army investigators — not including the most notorious U.S. atrocity, the 1968 My Lai massacre.

Though not a complete accounting of Vietnam war crimes, the archive is the largest such collection to surface to date. About 9,000 pages, it includes investigative files, sworn statements by witnesses and status reports for top military brass.

The records describe recurrent attacks on ordinary Vietnamese — families in their homes, farmers in rice paddies, teenagers out fishing. Hundreds of soldiers, in interviews with investigators and letters to commanders, described a violent minority who murdered, raped and tortured with impunity.

Abuses were not confined to a few rogue units, a Times review of the files found. They were uncovered in every Army division that operated in Vietnam.

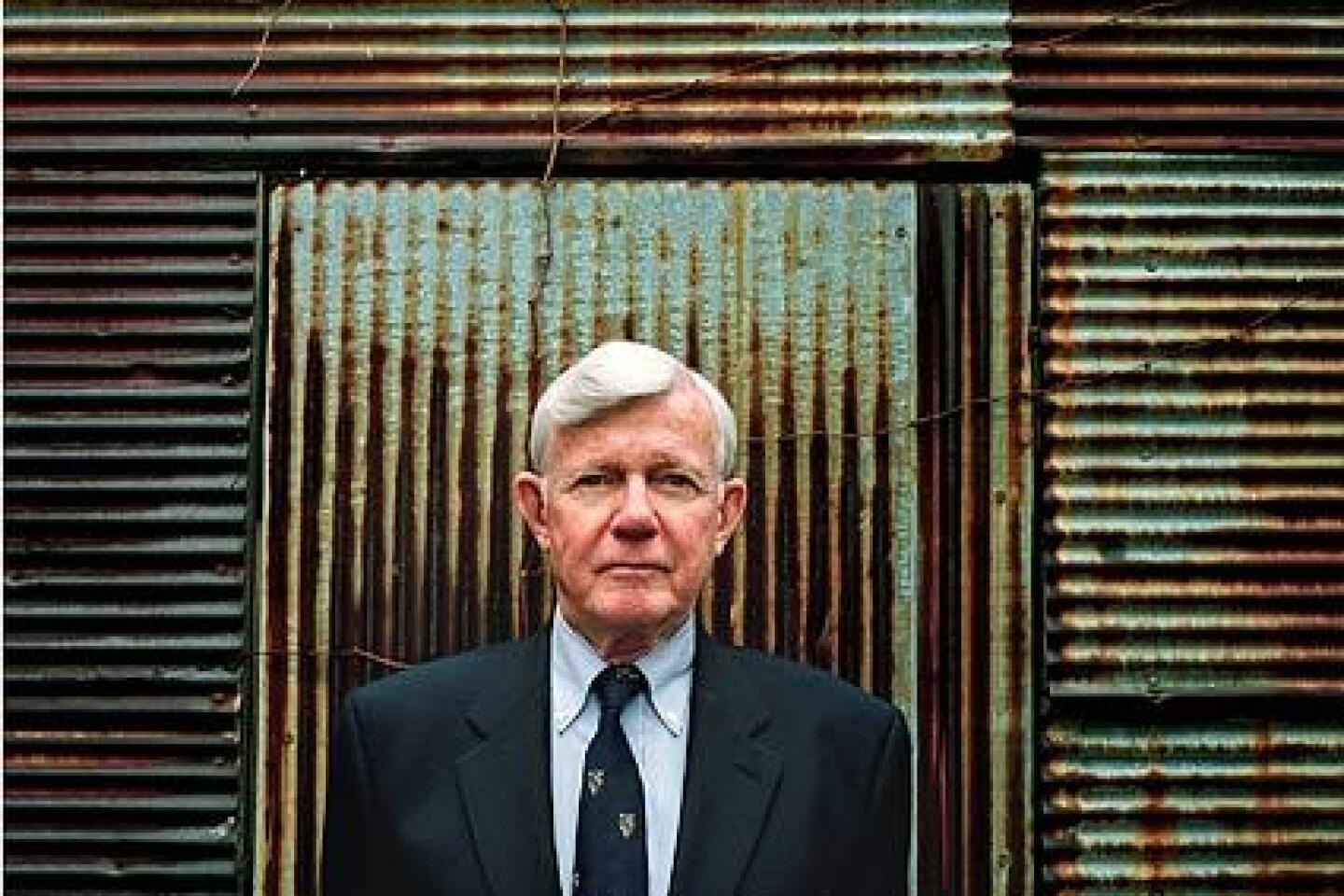

Retired Brig. Gen. John H. Johns, a Vietnam veteran who served on the task force, says he once supported keeping the records secret but now believes they deserve wide attention in light of alleged attacks on civilians and abuse of prisoners in Iraq.

“We can’t change current practices unless we acknowledge the past,” says Johns, 78.

Among the substantiated cases in the archive:

Seven massacres from 1967 through 1971 in which at least 137 civilians died.

Seventy-eight other attacks on noncombatants in which at least 57 were killed, 56 wounded and 15 sexually assaulted.

One hundred forty-one instances in which U.S. soldiers tortured civilian detainees or prisoners of war with fists, sticks, bats, water or electric shock.

Investigators determined that evidence against 203 soldiers accused of harming Vietnamese civilians or prisoners was strong enough to warrant formal charges. These “founded” cases were referred to the soldiers’ superiors for action.

Ultimately, 57 of them were court-martialed and just 23 convicted, the records show.

Fourteen received prison sentences ranging from six months to 20 years, but most won significant reductions on appeal. The stiffest sentence went to a military intelligence interrogator convicted of committing indecent acts on a 13-year-old girl in an interrogation hut in 1967.

He served seven months of a 20-year term, the records show.

Many substantiated cases were closed with a letter of reprimand, a fine or, in more than half the cases, no action at all.

There was little interest in prosecuting Vietnam war crimes, says Steven Chucala, who in the early 1970s was legal advisor to the commanding officer of the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division. He says he disagreed with the attitude but understood it.

“Everyone wanted Vietnam to go away,” says Chucala, now a civilian attorney for the Army at Ft. Belvoir in Virginia.

In many cases, suspects had left the service. The Army did not attempt to pursue them, despite a written opinion in 1969 by Robert E. Jordan III, then the Army’s general counsel, that ex-soldiers could be prosecuted through courts-martial, military commissions or tribunals.

“I don’t remember why it didn’t go anywhere,” says Jordan, now a lawyer in Washington.

Top Army brass should have demanded a tougher response, says retired Lt. Gen. Robert G. Gard, who oversaw the task force as a brigadier general at the Pentagon in the early 1970s.

“We could have court-martialed them but didn’t,” Gard says of soldiers accused of war crimes. “The whole thing is terribly disturbing.”

Early-Warning System

In March 1968, members of the 23rd Infantry Division slaughtered about 500 Vietnamese civilians in the hamlet of My Lai. Reporter Seymour Hersh exposed the massacre the following year.By then, Gen. William C. Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam at the time of My Lai, had become Army chief of staff. A task force was assembled from members of his staff to monitor war crimes allegations and serve as an early-warning system.

Over the next few years, members of the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group reviewed Army investigations and wrote reports and summaries for military brass and the White House.

The records were declassified in 1994, after 20 years as required by law, and moved to the National Archives in College Park, Md., where they went largely unnoticed.

The Times examined most of the files and obtained copies of about 3,000 pages — about a third of the total — before government officials removed them from the public shelves, saying they contained personal information that was exempt from the Freedom of Information Act.

In addition to the 320 substantiated incidents, the records contain material related to more than 500 alleged atrocities that Army investigators could not prove or that they discounted.

Johns says many war crimes did not make it into the archive. Some were prosecuted without being identified as war crimes, as required by military regulations. Others were never reported.

In a letter to Westmoreland in 1970, an anonymous sergeant described widespread, unreported killings of civilians by members of the 9th Infantry Division in the Mekong Delta — and blamed pressure from superiors to generate high body counts.

“A batalion [sic] would kill maybe 15 to 20 [civilians] a day. With 4 batalions in the brigade that would be maybe 40 to 50 a day or 1200 to 1500 a month, easy,” the unnamed sergeant wrote. “If I am only 10% right, and believe me it’s lots more, then I am trying to tell you about 120-150 murders, or a My Lay [sic] each month for over a year.”

A high-level Army review of the letter cited its “forcefulness,” “sincerity” and “inescapable logic,” and urged then-Secretary of the Army Stanley R. Resor to make sure the push for verifiable body counts did not “encourage the human tendency to inflate the count by violating established rules of engagement.”

Investigators tried to find the letter writer and “prevent his complaints from reaching” then-Rep. Ronald V. Dellums (D-Oakland), according to an August 1971 memo to Westmoreland.

The records do not say whether the writer was located, and there is no evidence in the files that his complaint was investigated further.

Pvt. Henry

James D. “Jamie” Henry was 19 in March 1967, when the Army shaved his hippie locks and packed him off to boot camp.He had been living with his mother in Sonoma County, working as a hospital aide and moonlighting as a flower child in Haight-Ashbury, when he received a letter from his draft board. As thousands of hippies poured into San Francisco for the upcoming “Summer of Love,” Henry headed for Ft. Polk, La.

Soon he was on his way to Vietnam, part of a 100,000-man influx that brought U.S. troop strength to 485,000 by the end of 1967. They entered a conflict growing ever bloodier for Americans — 9,378 U.S. troops would die in combat in 1967, 87% more than the year before.

Henry was a medic with B Company of the 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division. He described his experiences in a sworn statement to Army investigators several years later and in recent interviews with The Times.

In the fall of 1967, he was on his first patrol, marching along the edge of a rice paddy in Quang Nam province, when the soldiers encountered a teenage girl.

“The guy in the lead immediately stops her and puts his hand down her pants,” Henry said. “I just thought, ‘My God, what’s going on?’ ”

A day or two later, he saw soldiers senselessly stabbing a pig.

“I talked to them about it, and they told me if I wanted to live very long, I should shut my mouth,” he told Army investigators.

Henry may have kept his mouth shut, but he kept his eyes and ears open.

On Oct. 8, 1967, after a firefight near Chu Lai, members of his company spotted a 12-year-old boy out in a rainstorm. He was unarmed and clad only in shorts.

“Somebody caught him up on a hill, and they brought him down and the lieutenant asked who wanted to kill him,” Henry told investigators.

Two volunteers stepped forward. One kicked the boy in the stomach. The other took him behind a rock and shot him, according to Henry’s statement. They tossed his body in a river and reported him as an enemy combatant killed in action.

Three days later, B Company detained and beat an elderly man suspected of supporting the enemy. He had trouble keeping pace as the soldiers marched him up a steep hill.

“When I turned around, two men had him, one guy had his arms, one guy had his legs and they threw him off the hill onto a bunch of rocks,” Henry’s statement said.

On Oct. 15, some of the men took a break during a large-scale “search-and-destroy” operation. Henry said he overheard a lieutenant on the radio requesting permission to test-fire his weapon, and went to see what was happening.

He found two soldiers using a Vietnamese man for target practice, Henry said. They had discovered the victim sleeping in a hut and decided to kill him for sport.

“Everybody was taking pot shots at him, seeing how accurate they were,” Henry said in his statement.

Back at base camp on Oct. 23, he said, members of the 1st Platoon told him they had ambushed five unarmed women and reported them as enemies killed in action. Later, members of another platoon told him they had seen the bodies.

Tet Offensive

Capt. Donald C. Reh, a 1964 graduate of West Point, took command of B Company in November 1967. Two months later, enemy forces launched a major offensive during Tet, the Vietnamese lunar New Year.In the midst of the fighting, on Feb. 7, the commander of the 1st Battalion, Lt. Col. William W. Taylor Jr., ordered an assault on snipers hidden in a line of trees in a rural area of Quang Nam province. Five U.S. soldiers were killed. The troops complained bitterly about the order and the deaths, Henry said.

The next morning, the men packed up their gear and continued their sweep of the countryside. Soldiers discovered an unarmed man hiding in a hole and suspected that he had supported the enemy the previous day. A soldier pushed the man in front of an armored personnel carrier, Henry said in his statement.

“They drove over him forward which didn’t kill him because he was squirming around, so the APC backed over him again,” Henry’s statement said.

Then B Company entered a hamlet to question residents and search for weapons. That’s where Henry set down his weapon and lighted a cigarette in the shelter of a hut.

A radio operator sat down next to him, and Henry was listening to the chatter. He heard the leader of the 3rd Platoon ask Reh for instructions on what to do with 19 civilians.

“The lieutenant asked the captain what should be done with them. The captain asked the lieutenant if he remembered the op order (operation order) that came down that morning and he repeated the order which was ‘kill anything that moves,’ ” Henry said in his statement. “I was a little shook because I thought the lieutenant might do it.”

Henry said he left the hut and walked toward Reh. He saw the captain pick up the phone again, and thought he might rescind the order.

Then soldiers pulled a naked woman of about 19 from a dwelling and brought her to where the other civilians were huddled, Henry said.

“She was thrown to the ground,” he said in his statement. “The men around the civilians opened fire and all on automatic or at least it seemed all on automatic. It was over in a few seconds. There was a lot of blood and flesh and stuff flying around .

“I looked around at some of my friends and they all just had blank looks on their faces . The captain made an announcement to all the company, I forget exactly what it was, but it didn’t concern the people who had just been killed. We picked up our stuff and moved on.”

Henry didn’t forget, however. “Thirty seconds after the shooting stopped,” he said, “I knew that I was going to do something about it.”

Homecoming

For his combat service, Henry earned a Bronze Star with a V for valor, and a Combat Medical Badge, among other awards. A fellow member of his unit said in a sworn statement that Henry regularly disregarded his own safety to save soldiers’ lives, and showed “compassion and decency” toward enemy prisoners.When Henry finished his tour and arrived at Ft. Hood, Texas, in September 1968, he went to see an Army legal officer to report the atrocities he’d witnessed.

The officer advised him to keep quiet until he got out of the Army, “because of the million and one charges you can be brought up on for blinking your eye,” Henry says. Still, the legal officer sent him to see a Criminal Investigation Division agent.

The agent was not receptive, Henry recalls.

“He wanted to know what I was trying to pull, what I was trying to put over on people, and so I was just quiet. I told him I wouldn’t tell him anything and I wouldn’t say anything until I got out of the Army, and I left,” Henry says.

Honorably discharged in March 1969, Henry moved to Canoga Park, enrolled in community college and helped organize a campus chapter of Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

Then he ended his silence: He published his account of the massacre in the debut issue of Scanlan’s Monthly, a short-lived muckraking magazine, which hit the newsstands on Feb. 27, 1970. Henry held a news conference the same day at the Los Angeles Press Club.

Records show that an Army operative attended incognito, took notes and reported back to the Pentagon.

A faded copy of Henry’s brief statement, retrieved from the Army’s files, begins:

“On February 8, 1968, nineteen (19) women and children were murdered in Viet-Nam by members of 3rd Platoon, ‘B’ Company, 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry .

“Incidents similar to those I have described occur on a daily basis and differ one from the other only in terms of numbers killed,” he told reporters. A brief article about his remarks appeared inside the Los Angeles Times the next day.

Army investigators interviewed Henry the day after the news conference. His sworn statement filled 10 single-spaced typed pages. Henry did not expect anything to come of it: “I never got the impression they were ever doing anything.”

In 1971, Henry joined more than 100 other veterans at the Winter Soldier Investigation, a forum on war crimes sponsored by Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

The FBI put the three-day gathering at a Detroit hotel under surveillance, records show, and Nixon administration officials worked behind the scenes to discredit the speakers as impostors and fabricators.

Although the administration never publicly identified any fakers, one of the organization’s leaders admitted exaggerating his rank and role during the war, and a cloud descended on the entire gathering.

“We tried to get as much publicity as we could, and it just never went anywhere,” Henry says. “Nothing ever happened.”

After years of dwelling on the war, he says, he “finally put it in a closet and shut the door.”

The Investigation

Unknown to Henry, Army investigators pursued his allegations, tracking down members of his old unit over the next 3 1/2 years.Witnesses described the killing of the young boy, the old man tossed over the cliff, the man used for target practice, the five unarmed women, the man thrown beneath the armored personnel carrier and other atrocities.

Their statements also provided vivid corroboration of the Feb. 8, 1968, massacre from men who had observed the day’s events from various vantage points.

Staff Sgt. Wilson Bullock told an investigator at Ft. Carson, Colo., that his platoon had captured 19 “women, children, babies and two or three very old men” during the Tet offensive.

“All of these people were lined up and killed,” he said in a sworn statement. “When it, the shooting, stopped, I began to return to the site when I observed a naked Vietnamese female run from the house to the huddle of people, saw that her baby had been shot. She picked the baby up and was then shot and the baby shot again.”

Gregory Newman, another veteran of B Company, told an investigator at Ft. Myer, Va., that Capt. Reh had issued an order “to search and destroy and kill anything in the village that moved.”

Newman said he was carrying out orders to kill the villagers’ livestock when he saw a naked girl head toward a group of civilians.

“I saw them begging before they were shot,” he recalled in a sworn statement.

Donald R. Richardson said he was at a command post outside the hamlet when he heard a platoon leader on the radio ask what to do with 19 civilians.

“The cpt said something about kill anything that moves and the lt on the other end said ‘Their [sic] moving,’ ” according to Richardson’s sworn account. “Just then the gunfire was heard.”

William J. Nieset, a rifle squad leader, told investigators that he was standing next to a radio operator and heard Reh say: “My instructions from higher are to kill everything that moves.”

Robert D. Miller said he was the radio operator for Lt. Johnny Mack Carter, commander of the 3rd Platoon. Miller said that when Carter asked Reh what to do with the 19 civilians, the captain instructed him to follow the “operation order.”

Carter immediately sought two volunteers to shoot the civilians, Miller said under oath.

“I believe everyone knew what was going to happen,” he said, “so no one volunteered except one guy known only to me as ‘Crazy.’ ”

“A few minutes later, while the Vietnamese were huddled around in a circle Lt Carter and ‘Crazy’ started shooting them with their M-16’s on automatic,” Miller’s statement says.

Carter had just left active duty when an investigator questioned him under oath in Palmetto, Fla., in March 1970.

“I do not recall any civilians being picked up and categorically stated that I did not order the killing of any civilians, nor do I know of any being killed,” his statement said.

An Army investigator called Reh at Ft. Myer. Reh’s attorney called back. The investigator made notes of their conversation: “If the interview of Reh concerns atrocities in Vietnam then he had already advised Reh not to make any statement.”

As for Lt. Col. Taylor, two soldiers described his actions that day.

Myran Ambeau, a rifleman, said he was standing five feet from the captain and heard him contact the battalion commander, who was in a helicopter overhead. (Ambeau did not identify Reh or Taylor by name.)

“The battalion commander told the captain, ‘If they move, shoot them,’ ” according to a sworn statement that Ambeau gave an investigator in Little Rock, Ark. “The captain verified that he had heard the command, he then transmitted the instruction to Lt Carter.

“Approximately three minutes later, there was automatic weapons fire from the direction where the prisoners were being held.”

Gary A. Bennett, one of Reh’s radio operators, offered a somewhat different account. He said the captain asked what he should do with the detainees, and the battalion commander replied that it was a “search and destroy mission,” according to an investigator’s summary of an interview with Bennett.

Bennett said he did not believe the order authorized killing civilians and that, although he heard shooting, he knew nothing about a massacre, the summary says. Bennett refused to provide a sworn statement.

An Army investigator sat down with Taylor at the Army War College in Carlisle, Pa. Taylor said he had never issued an order to kill civilians and had heard nothing about a massacre on the date in question. But the investigator had asked Taylor about events occurring on Feb. 9, 1968 — a day after the incident.

Three and a half years later, an agent tracked Taylor down at Ft. Myer and asked him about Feb. 8. Taylor said he had no memory of the day and did not have time to provide a sworn statement. He said he had a “pressing engagement” with “an unidentified general officer,” the agent wrote.

Investigators wrote they could not find Pvt. Frank Bonilla, the man known as “Crazy.” The Times reached him at his home on Oahu in March.

Bonilla, now 58 and a hotel worker, says he recalls an order to kill the civilians, but says he does not remember who issued it. “Somebody had a radio, handed it to someone, maybe a lieutenant, said the man don’t want to see nobody standing,” he said.

Bonilla says he answered a call for volunteers but never pulled the trigger.

“I couldn’t do it. There were women and kids,” he says. “A lot of guys thought that I had something to do with it because they saw me going up there . Nope I just turned the other way. It was like, ‘This ain’t happening.’ ”

Afterward, he says, “I remember sitting down with my head between my knees. Is that for real? Someone said, ‘Keep your mouth shut or you’re not going home.’ ”

He says he does not know who did the shooting.

The Outcome

The Criminal Investigation Division assigned Warrant Officer Jonathan P. Coulson in Los Angeles to complete the investigation and write a final report on the “Henry Allegation.” He sent his findings to headquarters in Washington in January 1974.Evidence showed that the massacre did occur, the report said. The investigation also confirmed all but one of the other killings that Henry had described. The one exception was the elderly man thrown off a cliff. Coulson said it could not be determined whether the victim was alive when soldiers tossed him.

The evidence supported murder charges in five incidents against nine “subjects,” including Carter and Bonilla, Coulson wrote. Those two carried out the Feb. 8 massacre, along with “other unidentified members of their element,” the report said.

Investigators determined that there was not enough evidence to charge Reh with murder, because of conflicting accounts “as to the actual language” he used.

But Reh could be charged with dereliction of duty for failing to investigate the killings, the report said.

Coulson conferred with an Army legal advisor, Capt. Robert S. Briney, about whether the evidence supported charges against Taylor.

They decided it did not. Even if Taylor gave an order to kill the Vietnamese if they moved, the two concluded, “it does not constitute an order to kill the prisoners in the manner in which they were executed.”

The War Crimes Working Group records give no indication that action was taken against any of the men named in the report.

Briney, now an attorney in Phoenix, says he has forgotten details of the case but recalls a reluctance within the Army to pursue such charges.

“They thought the war, if not over, was pretty much over. Why bring this stuff up again?” he says.

Years Later

Taylor retired in 1977 with the rank of colonel. In a recent interview outside his home in northern Virginia, he said, “I would not have given an order to kill civilians. It’s not in my makeup. I’ve been in enough wars to know that it’s not the right thing to do.”Reh, who left active duty in 1978 and now lives in Northern California, declined to be interviewed by The Times.

Carter, a retired postal worker living in Florida, says he has no memory of his combat experiences. “I guess I’ve wiped Vietnam and all that out of my mind. I don’t remember shooting anyone or ordering anyone to shoot,” he says.

He says he does not dispute that a massacre took place. “I don’t doubt it, but I don’t remember . Sometimes people just snap.”

Henry was re-interviewed by an Army investigator in 1972, and was never contacted again. He drifted away from the antiwar movement, moved north and became a logger in California’s Sierra Nevada foothills. He says he had no idea he had been vindicated — until The Times contacted him in 2005.

Last fall, he read the case file over a pot of coffee at his dining room table in a comfortably worn house, where he lives with his wife, Patty.

“I was a wreck for a couple days,” Henry, now 59, wrote later in an e-mail. “It was like a time warp that put me right back in the middle of that mess. Some things long forgotten came back to life. Some of them were good and some were not.

“Now that whole stinking war is back. After you left, I just sat in my chair and shook for a couple hours. A slight emotional stress fracture?? Don’t know, but it soon passed and I decided to just keep going with this business. If it was right then, then it still is.”

Times researcher Janet Lundblad contributed to this report.

*

About this report

Nick Turse is a freelance journalist living in New Jersey. Deborah Nelson is a staff writer in The Times’ Washington bureau.

This report is based in part on records of the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group filed at the National Archives in College Park, Md. The collection includes 241 case summaries that chronicle more than 300 substantiated atrocities by U.S. forces and 500 unconfirmed allegations.

The archive includes reports of war crimes by the 101st Airborne Division’s Tiger Force that the Army listed as unconfirmed. The Toledo Blade documented the atrocities in a 2003 newspaper series.

Turse came across the collection in 2002 while researching his doctoral dissertation for the Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health at Columbia University.

Turse and Nelson also reviewed Army inspector general records in the National Archives; FBI and Army Criminal Investigation Division records; documents shared by military veterans; and case files and related records in the Col. Henry Tufts Archive at the University of Michigan.

A selection of documents used in preparing this report can be found at latimes.com/vietnam.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.