A wispy white spume spills from an exhaust stack as Stadoil’s carbon dioxide was escaping into the atmosphere. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)

The Sleipner complex in the North Sea, an hours’ flight off the coast of Norway. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)

TECHNOLOGY: An 11-story unit in the North Sea traps excess carbon dioxide, which is then pumped into the ground. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)

Advertisement

Platform manager Helge Smaamo stands on a platform landing overlooking the 8000-ton CO2 unit. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)

Crew members head off the helipad after arriving on the Sleipner Platform in the North Sea. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)

Sleipner complex platform manager Helge Smaamo looks up into a maze of pipes making up part of the platform’s 34,000-ton Rubik’s cube of color-coded conduits, control valves and compressors. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)

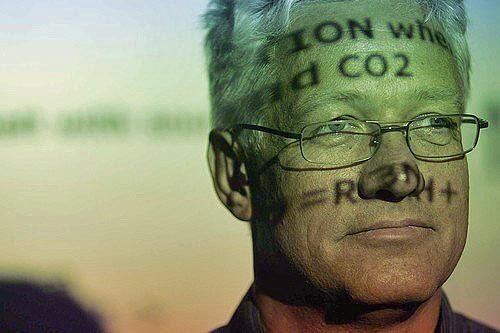

‘This is the only way for the fossil fuel industries to survive -- to become part of the solution.’

Tor Fjaeran, Statoil senior vice president for the environment (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)

Advertisement

STRATEGY: In the North Sea, a safety officer on the Sleipner platform looks toward the carbon-capture unit, part of the carbon dioxide injection process that saves Statoil $53 million a year in Norwegian taxes on greenhouse gas emissions. Critics of such operations worry about the long-term safety of the carbon dioxide reservoirs. (Brian Vander Brug / LAT)