Subtle signs of a turnaround on a troubled L.A. campus

- Share via

Locke High School English teacher Katy Bridger tried to give her fifth-period seniors a test while Byron Gordon sharpened pencils noisily, Deon Crockett wandered the room complaining at full volume and a girl cursed just as loudly at Deon for being rude. Daniel Dominguez dozed in the back.

Pressing on, Bridger, a 23-year-old recent political science graduate from Tennessee, told students to put away their cellphones and iPods. One student demanded to know why, muttering the F-word.

Despite the momentary chaos and disrespect -- and the fact that half the students were absent -- this class represents improvement at one of the most troubled campuses in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

For years, Locke, on the edge of Watts, has had among the state’s lowest test scores and highest dropout rates. In 2004, 1,451 students enrolled as freshmen; just 261 graduated four years later. Of them, only 85 had completed the courses required to apply to a University of California or California State University school.

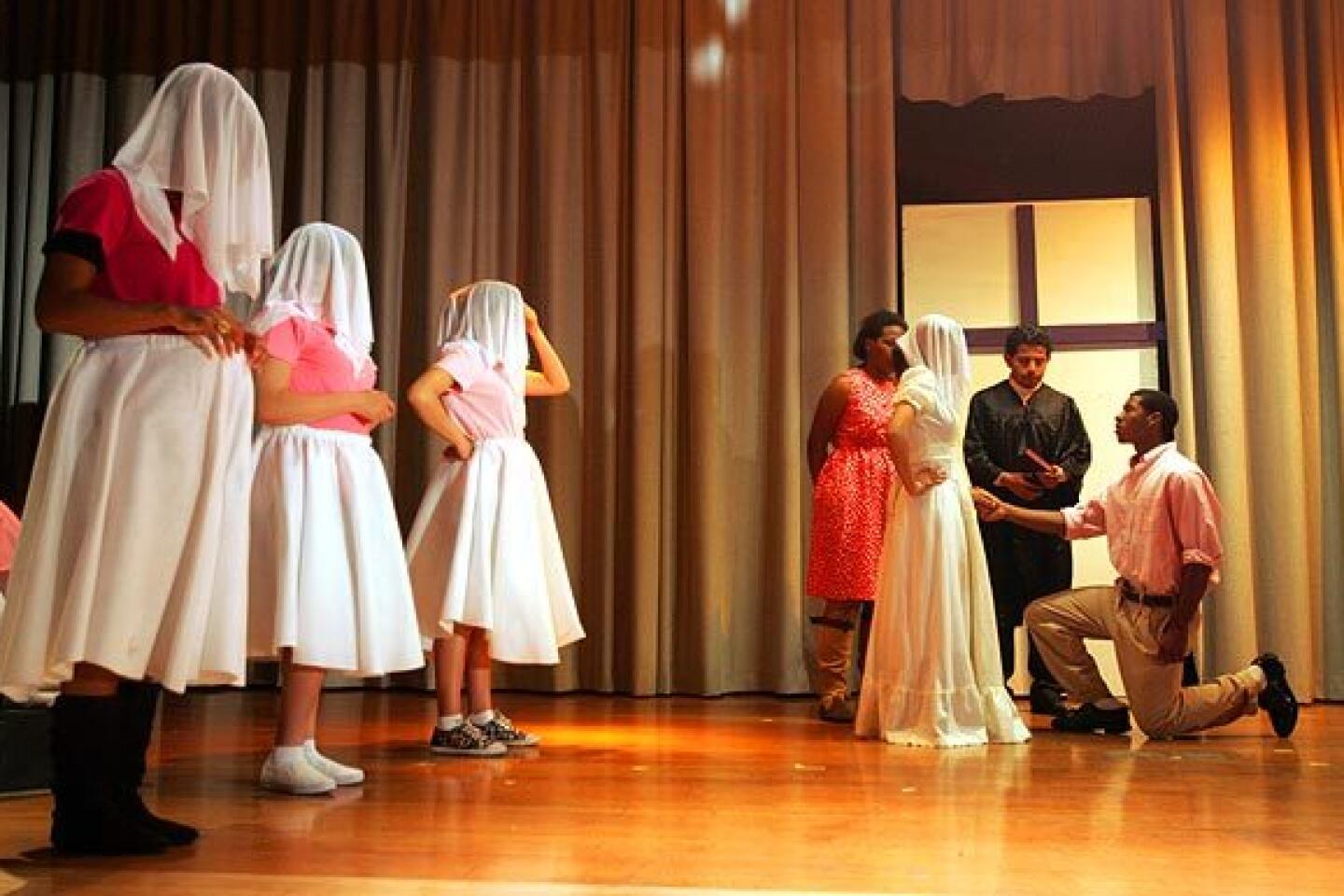

A year ago, Green Dot Public Schools, which runs 12 charters serving the city’s urban poor, took over the school. The effort to transform Locke has been a nationally watched test of whether such a large, deeply impoverished urban high school could be transformed by a charter operator. Charter schools are publicly funded but operate beyond the direct control of school districts, exempt from many regulations and union contracts.

New foundation

Locke, which holds its graduation today, remains a troubled school, and Green Dot’s strategy has relied on extra funds that may not be sustainable or readily replicable.

But despite those caveats, a qualified turnaround appears to be emerging.

Students say the campus is safer and calmer. The teachers, although mostly young and inexperienced, receive praise for being devoted and effective. There are signs of academic progress. Students repeat one point over and over: Instruction is better and nearly all teachers work hard and expect them to achieve.

Byron, the student who was sharpening pencils during the test, began the year an unmotivated senior and a Green Dot skeptic. “I thought Green Dot was going to be gone after the first month,” Byron said. “I didn’t think they were going to change anything.”

In September, Bridger had to explain the difference between a noun and a verb. She’s now well past those preliminaries.

“What kind of person does Lady MacBeth want her husband to be?” she asked her class a few days after the test.

“A murderer,” said Deon, appearing more focused that day.

“What does Lady Macbeth want her husband to seem to be?” Bridger continued.

“A hero, a leader,” said Daniel, who was awake that day. He works 35 hours a week at Subway, for $8.25 an hour, to support his girlfriend and their two children.

The test Bridger had given was one of a series of benchmark exams that Green Dot uses to measure progress. When the results came, they showed gains: The average score for Bridger’s fifth-period class, roughly converted to the state’s norms, would be in the low range of “basic,” one level below the state’s goal of “proficiency.” That’s not spectacular, but as 11th graders, 63% of Locke students had tested as “below basic” or worse.

Tough conditions

Locke’s student body includes many who are far behind in credits, others with severe to moderate disabilities, and a small but steady flow of teens returning to school after serving time for criminal activity.

Academic growth over the last year has been uneven, according to Green Dot data. And that has prompted concern. “My nightmare is that the state test scores come in and you’re judged by that,” said Green Dot founder Steve Barr.

Leaders of traditional schools frequently complain about being evaluated mainly by test results; such concerns are often dismissed by charter school operators, including Green Dot.

“We have not unlocked all the mysteries,” said Marco Petruzzi, Green Dot’s chief executive. “We’re very humble about that.”

Daniel and Deon are among about 307 seniors who completed their course work for graduation. Several dozen others will participate in today’s ceremony because they are close enough to finish in summer school. More than 100 seniors didn’t make it.

Byron was kicked out of a Pomona high school two years ago for fighting. He moved in with his father near Locke in part, he said, to escape bad influences, including some in his family. Last year, he got Bs and Cs and he flunked a class.

“Last year it didn’t matter,” said Byron, who earned A’s and Bs this year. “I never had nobody on me like I do now. This year, any class I decide to mess in, I will get in trouble with the teacher. They don’t expect me to mess up.”

Green Dot replaced most of the old Locke faculty and split the school into eight smaller academies. Much of the staff is young, and only 15% have fully completed teacher credentialing requirements. Half have taught for three years or less. And half are 28 or younger.

But many make up in enthusiasm what they lack in years. Bridger regularly spends 12 hours a day on campus, typically arriving just after 6 a.m. When school ends, some students remain seated in her classroom and others file in for extra assistance, to make up work, to help Bridger with projects or just to hang out.

The school’s youth-oriented staffing allows Green Dot to pay higher starting salaries while still maintaining a payroll that averages below traditional public high schools in the area, according to a Times analysis.

Even before Green Dot, Locke had a contingent of energetic newcomers and capable veterans. The math department rebuilt a dormant calculus program, and 44 students enrolled in the class this year.

But the motivated teachers, experienced or not, received inconsistent support, which accelerated burnout, disillusionment and departure, said calculus teacher Fernando Avila.

“This became the place where a lot of teachers not performing in other schools ended up,” Avila said.

Teacher Elijah Woodson said the achievements of the prior staff are underappreciated. Against the Green Dot takeover all along, he nevertheless stayed on after Green Dot asked L.A. Unified to continue to provide teachers for students with disabilities. That will change next year, in part because Green Dot managers are dissatisfied with the way L.A. Unified handled the contracted teachers.

Woodson said he feels personally harassed, with administrators regularly observing and evaluating his teaching. During one visit they focused on a student who was asleep in class -- because of medication, Woodson said -- rather than on 20 others who were paying attention.

Being critiqued is something Green Dot employees must get used to. Bridger said she relies on observations to improve, although not all teachers report favorably on their administrators. And the Green Dot teachers union filed several grievances over pay and working conditions.

Some classes have exceeded 40 students, a dilemma for Green Dot, which prides itself on small classes. And although the staff has made a concerted effort to keep students in school, some have dropped off the radar. A few with serious discipline or attendance issues have recently been sent home.

Targeted teaching

To make classes more manageable, administrators have enrolled some especially challenging students in Locke 4, an academy whose Opportunities program consists of three classrooms set aside for students who are doing poorly or displaying serious behavior problems. The program also accepts students returning after being convicted of crimes.

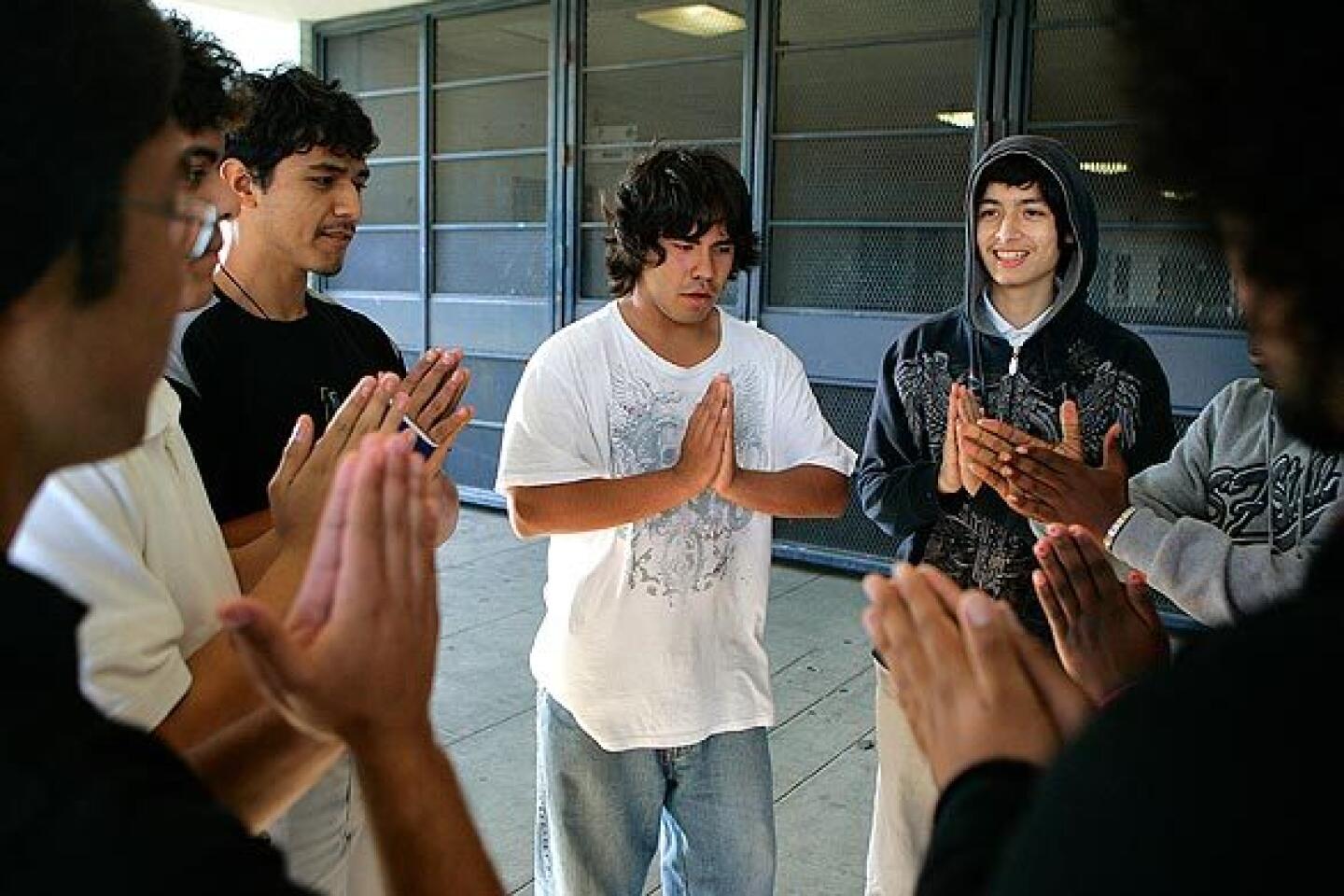

On a recent Monday, 14 students sat in an Opportunities class with one teacher and an aide -- Green Dot wanted especially small adult-to-student ratios for these youths. The posted class rules were simple: Stay seated during class; complete all of your work; be polite and respectful.

These expectations failed to achieve traction with several students, including a recently arriving freshman.

“Do you need help?” the teacher asked him.

“You need help,” he retorted, looking around for admiration from his peers. “You know, lady, I don’t like you.”

The group was assigned to organize an essay on juvenile justice after reviewing case studies of four young offenders. If students actually write the essay, they’ll get extra credit.

One table over from the ninth-grader, a wiry boy with slicked-back hair said he had landed in Locke 4 after punching a school security guard. He considers gang membership necessary to survive: “That’s almost part of life.”

Then he paused and offered something close to an endorsement of the new Locke: “Other schools, you have your enemies all the time. In this school everybody gets along. People talk to Bloods and Crips.”

He started to work on the essay: “These cases are like what happened to my friends. They got shot at and shot back.”

Last year, said senior Harold Thomas, “every other week a fight or something would be going on. I used to walk from the back to the front and all of a sudden, there was smoke coming from a classroom, and you’d hear the Fire Department coming.”

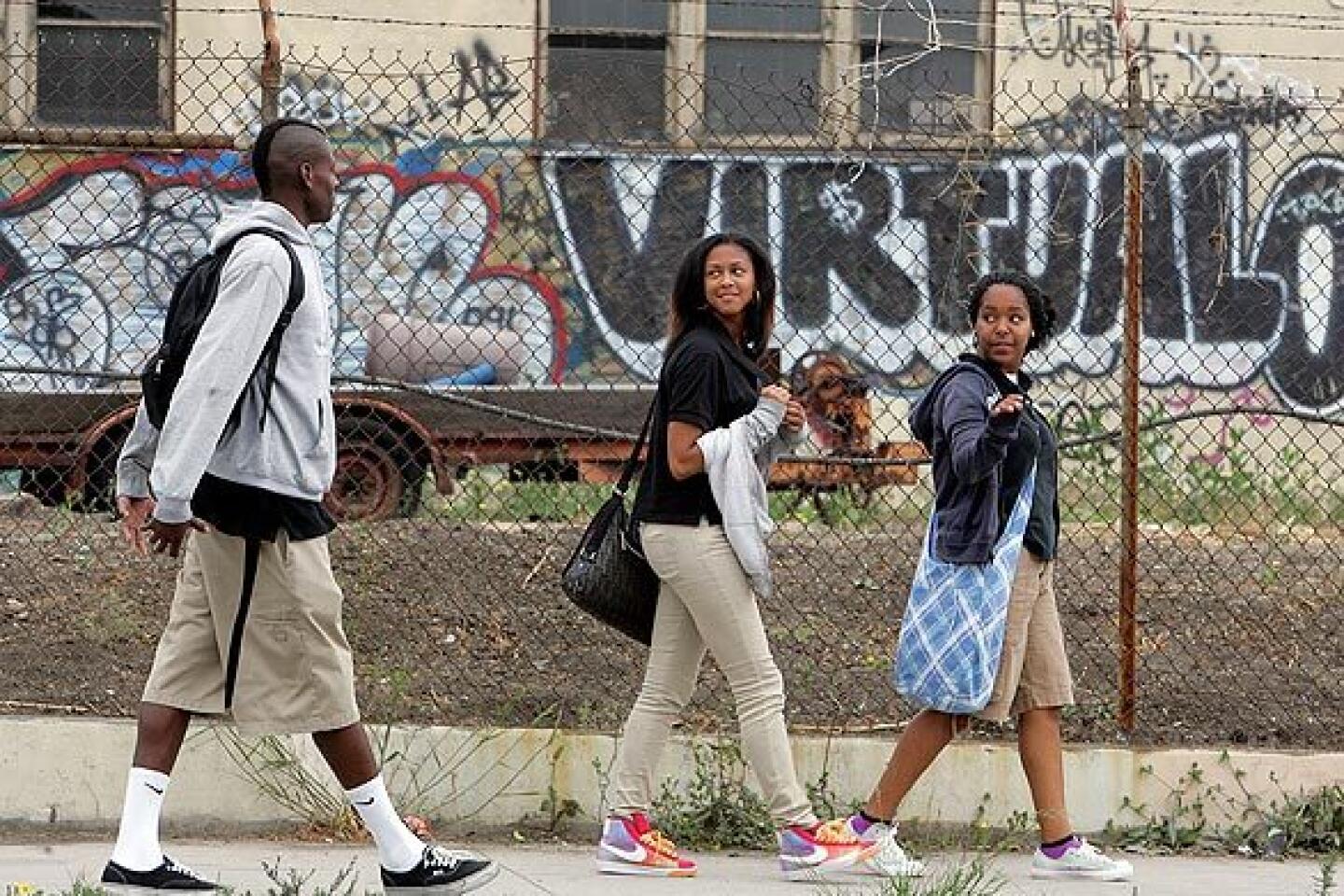

To secure the campus, Green Dot has spent $700,000 on security, which might prove unaffordable over time. The investment has helped to nearly eliminate fights and reduce graffiti and other forms of vandalism. The school has also fenced off areas on campus to boost security and has provided some bus service so students don’t have to traverse gang territories.

But no strategy can entirely screen out the realities of a tough neighborhood.

In April, a gunman wounded a student in front of campus as students were arriving.

Last October, two gang members approached Donald Wood as he waited at a city bus stop just off campus. The gunman aimed at his head, but the weapon misfired, Donald said.

On the subsequent try, a bullet struck his upper arm and another entered his back, where it remains embedded close to his spine. He missed about three months of school and had to give up plans to return to football and track.

Donald had brushes with the law that included possession of firearms and assault and battery, but before the shooting he had seemed determined to set a new course. He stopped by Locke over the summer to help a former teacher, Maggie Bushek, set up her classroom. And at one point, he told her he did not want to turn out like the hopeless youths he saw in court.

“I catched up on a lot of my credits and I learned a lot of things,” Donald said. “I feel good about my future.”

Moving forward

Through April, 52 students started or transferred into the Opportunity classrooms. Of those, two had dropped out and 14 exited the Green Dot system for other programs.

Donald could be the first to move into the other side of Locke 4, where older students short on credits take self-paced computer courses.

That’s where Porsha Westbrooks, 18, made up two years worth of credits in less than a year. On a Wednesday recently, Porsha, to the applause of classmates, zipped up a light blue graduation gown and rang a bell for a one-person procession that’s become a tradition among the 30 potential dropouts who are now expected to graduate.

“She was rebellious, and she was ditching,” said her mother, Deborah Wilson. Now, “she’s my miracle child.”

Most of these students attend a four-hour shift, and many like the shortened day, especially those with jobs.

But the richness of the curriculum is open to challenge. On a recent Monday, as part of a humanities unit, Harold was reviewing facts about music in the baroque period. The exercise was nothing more than rote memorization: He never actually listened to baroque music, which he pronounced “barrack.”

The two sectors of Locke 4 -- Opportunities and Advanced Path -- have allowed Green Dot to hold onto students who would have been unable to remain at a typical Green Dot start-up. Many probably would have dropped out of the old Locke.

Byron’s diploma was never in question, but he found himself this month in a situation he never anticipated -- among a handful of students auditioning to give the senior class speech. His didn’t get the nod, but he’ll celebrate being accepted by Tuskegee University in Alabama, Grambling State University in Louisiana and Jackson State University in Mississippi. He chose Cal State Northridge because, he said, it’s close to his “support system.” He’s not referring to his family.

“My resources,” he said, “the people I come to for help, the support I get -- is from Locke High.”

--

howard.blume@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.