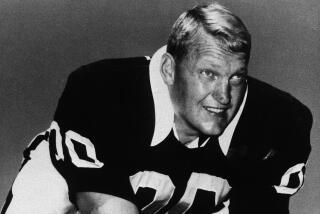

John Mackey dies at 69; NFL Hall of Famer revolutionized tight end position

- Share via

John Mackey, who helped revolutionize the NFL’s tight end position and whose post-football struggles with dementia became emblematic of the brutality of the game, has died. He was 69.

Mackey died Wednesday in Baltimore after a 10-year battle with frontal temporal dementia, the Baltimore Sun reported.

A former president of the NFL Players Assn., Mackey spent 10 seasons with the Baltimore Colts and San Diego Chargers, catching 331 passes for 5,236 yards and 38 touchdowns — including a 75-yard score on a tipped ball to help lift the Colts over the Dallas Cowboys in Super Bowl V in 1971.

“John laid the foundation on and off the field for modern NFL players,” Ozzie Newsome, general manager of the Baltimore Ravens, said Thursday in a statement.

Mackey’s speed and receiving ability changed how people thought of tight ends, not just as plodding blockers but as elusive offensive weapons. In 1992, Mackey was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame the second tight end to receive that honor. (Mike Ditka was the first.)

“It was like stepping from a biplane into the space shuttle” is how Mackey was described in an NFL Films highlight clip.

The late quarterback John Unitas once said Mackey “didn’t have the best of hands, but his running ability was second to none.”

Six of Mackey’s nine touchdown receptions in 1966 came on plays of 50 yards or longer.

Mackey further cemented his place in the hearts of Baltimore Colts fans when he refused to accept his ceremonial Hall of Fame ring in Indianapolis, where the franchise had relocated.

“Baltimore and nowhere else,” Mackey reportedly told the NFL. He was presented the ring later that year during an exhibition game between New Orleans and Miami at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium.

Born Sept. 24, 1941, Mackey grew up on Long Island in New York and starred at Syracuse University. He was selected by the Colts in the second round of the 1963 draft, and made an immediate impact, averaging a career-best 20.7 yards per catch as a rookie. That got him to the Pro Bowl in his first year.

Mackey’s leadership extended beyond the bounds of his team. He was elected the first president of the players union after the 1970 NFL-AFL merger and organized a three-day strike that year that earned the players $11 million in pensions and benefits. In 1972 he filed an antitrust lawsuit that eventually secured the players free agency, which the union later bargained away.

Some believe he would have reached the Hall of Fame sooner had he not been so involved in the politics of the game. He was inducted in his 15th and final year of eligibility.

“All of the benefits of today’s players come from the foundation laid by John Mackey,” Newsome, a Hall of Fame tight end for the Cleveland Browns, told the Baltimore Sun. “He took risks. He stepped out. He was willing to be different.”

In retirement, Mackey suffered from dementia, and the cost of his medical care significantly exceeded his NFL pension of less that $2,500 a month. His wife, at 56, had to resume her job as a flight attendant to make ends meet and so the couple could have health insurance.

Mackey was reported by family members in 2006 to be angered and confused upon seeing then-Indianapolis Colts receiver Marvin Harrison wearing the same No. 88 jersey Mackey wore in Baltimore.

Four years ago, Mackey entered a full-time assisted-living facility. The NFL initially resisted paying disability income, claiming there was no link between football and brain injuries.

However, Mackey’s struggles eventually prompted the NFL and union to establish the “88 Plan” — a nod to his jersey number — which provides up to $88,000 a year for nursing care for former players suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s disease.

There have been extensive studies in recent years linking head injuries suffered by NFL players to problems later in life, including depression, dementia and, in some cases, suicide.

Besides his wife, Sylvia, Mackey is survived by a son, two daughters and six grandchildren.

sam.farmer@latimes.comtwitter.com/LATimesfarmer

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.