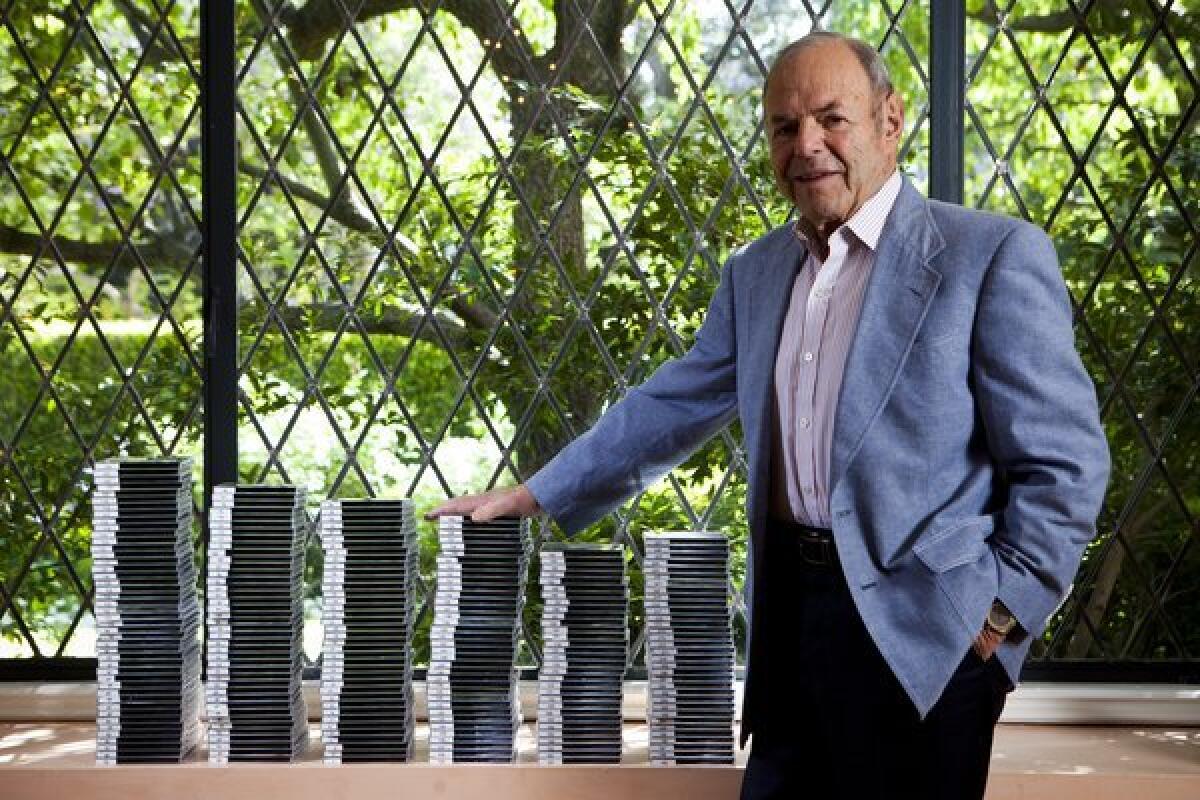

Joe Smith, record exec who helped everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Queen, dies

- Share via

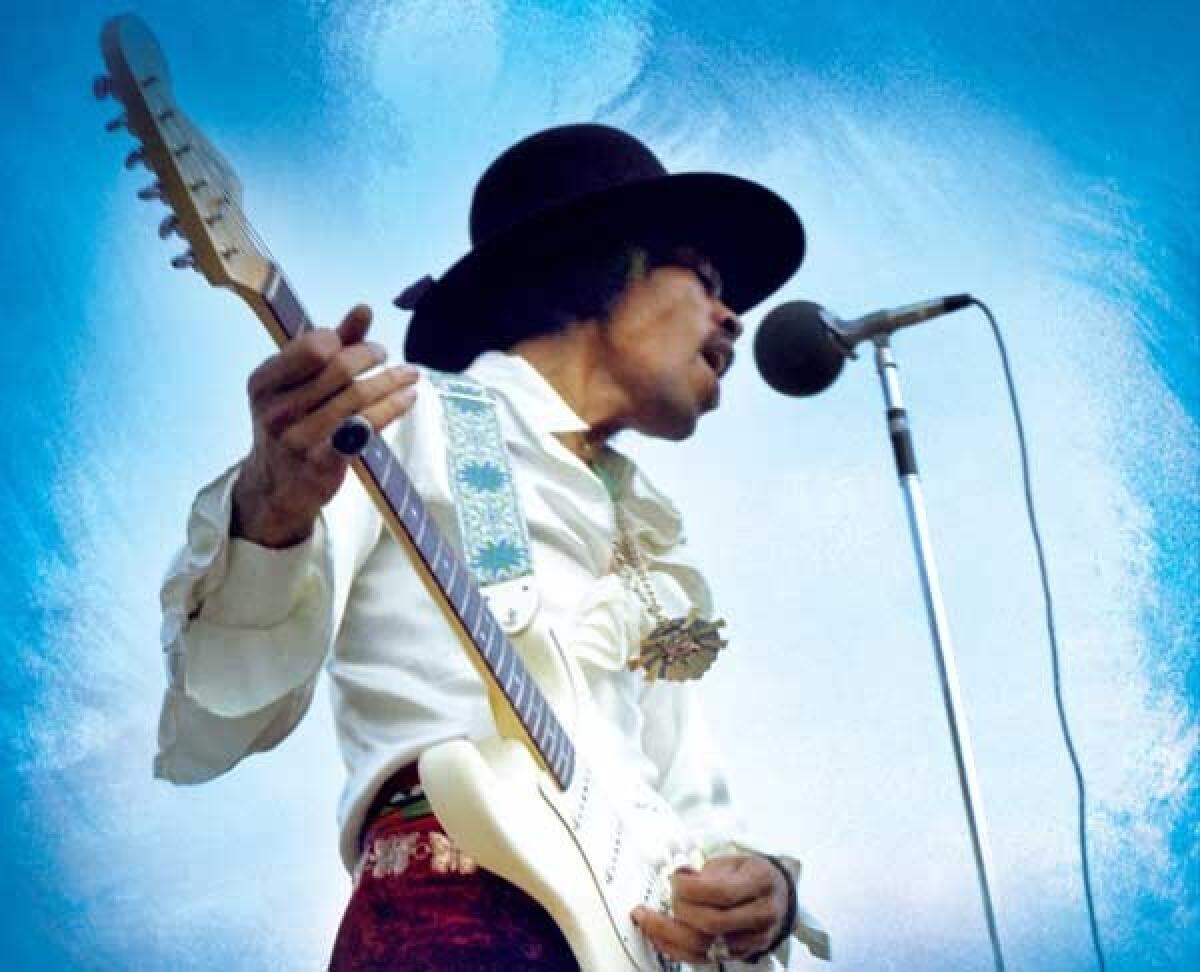

Some of the biggest, most influential pop and rock stars from the early days in vinyl to the CD era — Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead and Joni Mitchell, among them — have Joe Smith to thank for shepherding their careers.

Smith, who headed Capitol, Elektra/Asylum and Warner Bros. — three of the most important record labels — in a career that roughly spanned the age of rock ‘n’ roll, died in Los Angeles on Monday , his family announced. He was 91.

“Joe is one of the true giants of the record business,” said music and film mogul David Geffen in the 1990s. “Under his stewardship, Capitol Records and Warner Bros. Records were allowed to rise to new heights. He’s not just a great executive, he’s a true gentleman.”

Smith, known in the industry for his sharp wit and gregarious nature, worked with and helped develop the careers of hundreds of musicians, including Peter, Paul and Mary, the Cars, the Eagles, Queen and Motley Crue. And he signed blues singer Bonnie Raitt twice — first to Warner Bros. and later to Capitol.

Joseph Benjamin Smith was born Jan. 26, 1928. His father was an insurance agent and onetime bootlegger, his mother a homemaker who inspired Smith’s love for music. He was raised in Chelsea, Mass., and served in the Army after high school before earning a bachelor’s from Yale University in 1950. He spent the first part of his life pursuing a career in broadcasting as a sportscaster, but he eventually turned his attention to music.

Smith immersed himself in the music business as a DJ, at one point adopting the on-air persona “Cousin Joe” at a Virginia country station and later in Boston spinning the R&B and rock ’n’ roll sounds that defined the late 1950s. There, “he introduced a generation of teenagers to the first iterations of rock ’n’ roll,” said his son, Jeff.

But the tunes he played were often met with resistance. “The CYO (Christian Youth Organization) would try to censor what we played at record hops. They had a handout saying that venereal disease was on the rise in Boston, and that Elvis Presley and Joe Smith were responsible,” Smith told the Boston Herald in 2011.

In 1961, he moved to Los Angeles and began working with independent distributors but returned to radio shortly before being offered a job as Warner Bros’ national promotion manager and quickly rose through the ranks, becoming the company’s president in 1972.

During his tenure, Smith worked with some of rock’s biggest stars including Van Morrison, Alice Cooper, Deep Purple, Black Sabbath, The Doobie Brothers and the Grateful Dead, whose members reportedly tried persuading Smith to drop LSD so he’d “get” their music. He abstained.

Smith was appointed chairman at Elektra/Asylum Records in 1975, where the label expanded its musical roster from the acoustic sounds of Mitchell and Carly Simon to the punk and new wave music of bands such as X and the Cars.

He left the record company to join Home Sports Entertainment, a Warner Bros. division, as its president in 1983. He was also the first paid president of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, a post he held briefly before taking over Capitol, an ailing label he was tasked with bringing back to health.

While there, he stimulated the growth of Garth Brooks and resuscitated the career of Raitt, whom he once called “the most satisfying success story because I signed her twice ... and I saw her win seven Grammys.”

In the mid ’80s, Smith embarked on an ambitious personal project to document the who’s who of pop music. In the span of about two years, he interviewed more than 200 record executives, producers, songwriters, managers and musicians, including Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger, Elton John and Ella Fitzgerald. Excerpts were collected in his 1998 book, “Off the Record: An Oral History of Popular Music.” He donated the tapes to the Library of Congress in 2012.

Smith retired in 1993 at a time when the music industry was rapidly changing and becoming more corporate.

“In recent years, I find that my role has become mostly administrative and organizational,” Smith said at the time.

Smith later reflected on his long, successful career as an executive and what it took to get there.

“It took a lot of energy,” Smith told The Times in 1993. “Because your energy was immediately reflected in your enthusiasm. You didn’t go through layers of management. It was very personal.”

But Smith was most proud of the platform he had to push and nurture artists and their creativity.

“Well, I’m proud of encouraging and fostering a lot of people. I’m very proud of that, because I’m in awe of the creative process. I can’t do it. I can’t write and sing and perform, but I’ve been involved with music all my adult life, and to know that I maybe have pushed somebody in the right direction, or gave ’em the room to make a mistake, or make a bad record, and do something else — I think I like that.”

He is survived by his wife, Donnie, of 62 years, son, daughter, Julie, and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.