Op-Ed: Liberals are dangerously wrong about Citizens United: Money is speech

- Share via

Once upon a time, liberals pushed free speech at every opportunity. They lauded Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis for protecting unpopular views early in the last century. During the 1960s, Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement demanded the right to demonstrate politically on campus — and liberals championed the cause.

Now liberals want to empower the government to silence those who advance political ideas come election time. Hillary Clinton, for instance, has declared a litmus test for Supreme Court justices: a commitment to overrule Citizens United vs. the Federal Election Commission, the 2010 opinion upholding Americans’ 1st Amendment right to criticize or praise politicians running for office through nonprofit corporations. Worse still, Democratic senators have introduced a constitutional amendment that goes beyond reversing Citizens United and gives Congress substantial discretion to regulate how electoral debates are conducted.

This dramatic shift suggests that liberals have lost faith in their arguments — above all, at the ballot box. If you hold sway over the media and the academy and yet still fail to convince a majority of voters with your views, suppressing speech that counters those views can start to seem like a constitutional imperative. And make no mistake: beyond the rough-and-tumble of political campaigns, liberals continue to control the institutions that set the nation’s political agenda. As well-known data show, academics and journalists have, on average, quite liberal opinions.

Join the conversation on Facebook>>>

Elections, though, can disrupt this control, providing opportunities for citizens who aren’t academics or media representatives to speak about public matters. Among the citizens who tend to enter the fray at election time are those with the financial means to send out messages. These wealthy people don’t all lean right — the Koch brothers on the conservative side are countered by George Soros and Tom Steyer on the left — but as a group, they’re more ideologically balanced than journalists and academics.

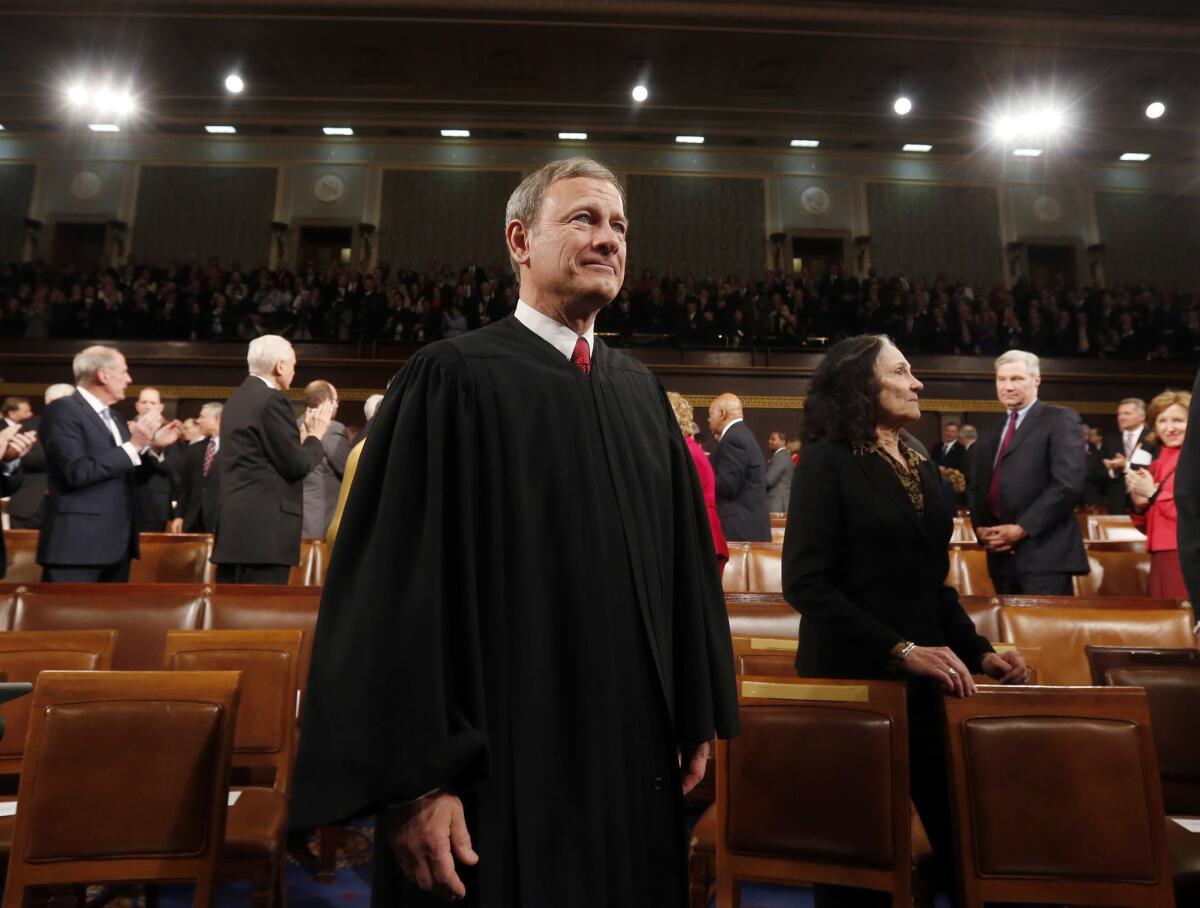

Even as liberals have abandoned their traditional support for free political speech, its protection has become central to Supreme Court jurisprudence under Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. At almost every turn, the Roberts court has made sure that campaign regulation is subject to ordinary 1st Amendment principles and doesn’t become, as liberals desire, a law unto itself, justifying restrictions that would be quickly ruled unconstitutional when other forms of expression are involved.

The Roberts court’s key insight is that any laws restricting electoral speech must obey “neutral principles.” That is to say, they should be generalizable beyond whatever dispute is at stake and whatever the characteristics of the parties involved.

Consider how the Roberts court has treated the mantra beloved of reformers who want paid political communications curbed at election time: “Money is not speech.” Outside campaign regulation, the Supreme Court’s 1st Amendment jurisprudence has banned any restrictions of expenditures that pay for expression. A government-imposed limit on, say, the amount of money a newspaper could spend for investigative reporters would be obviously unconstitutional. Why, then, should money spent on political campaigns be any different?

Or take a central issue in Citizens United, of whether the right to express views about candidates in a campaign extends to corporations. In finding that it does, the court embraced neutrality, relying on earlier 1st Amendment decisions that upheld the rights of corporations to talk about politics. In New York Times vs. Sullivan (1964), for instance, the court ruled in favor of the Times (a corporation), strengthening 1st Amendment protections against libel suits by public officials.

The 1st Amendment’s text supports corporate speech: “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech.” As set down by the framers, the right isn’t limited to particular kinds of speakers but bans the government regulation of speech, period. And if the 1st Amendment protects an individual’s right to speak, then why — if neutral principles are adhered to — shouldn’t a group of individuals, banded together in a partnership or other association, also enjoy that right? And if an association has that right, why would it lose it when it takes corporate form?

If the Roberts court majority has been relentless in trying to make campaign-finance jurisprudence consistent with general 1st Amendment principles, the liberal dissenters in these cases have been no less persistent in trying to carve out exceptions to permit the comprehensive regulation of campaigns.

In McCutcheon vs. FEC (2014), the court ruled unconstitutional a congressionally imposed limit on the amount of money that any individual could contribute to federal candidates during an election cycle. Justice Stephen G. Breyer, writing for all four dissenters, argued that the court should not apply the scrutiny typical of 1st Amendment cases but instead rely on legislators’ judgment about what best serves the public. His premise was that members of Congress are uniquely knowledgeable about how to design the rules for their campaigns.

The 1st Amendment guarantees freedom, not equality. Rights are exercised to radically unequal degrees, and the right to speech is no exception.

Not only did he ignore the substantial interest that politicians have in protecting their incumbency, Breyer was even willing to rethink the meaning of the 1st Amendment, arguing that it’s best understood as in part a “collective right,” with a goal of connecting the nation’s legislators to the true sentiments of the people. In this revised understanding, the 1st Amendment’s purposes are advanced when the government cracks down on speech (such as political donations from the wealthy) that may mislead lawmakers about where popular opinion stands on a given issue.

Breyer has found support in the academy for a 1st Amendment that allows the subordination of the individual voice to the collective will. Lawrence Lessig of Harvard Law School, for example, has argued that Congress must prevent the political “distortion” that occurs when legislators become dependent on the wealthy. Strong limits on campaign contributions can thus be constitutionally justified. By its logic, though, Lessig’s argument would permit Congress to regulate the press, too. Its power to distort opinion is surely as great as, or greater than, that of the wealthy.

But the 1st Amendment guarantees freedom, not equality. Rights are exercised to radically unequal degrees, and the right to speech is no exception. Some people are wealthy and can push their views with their money. Others work for the media or academia and can advance their opinions disproportionately in those settings. Still others command extra attention through celebrity. Most citizens have none of these advantages, but sometimes they join together to amplify their influence. In a free society, what law could succeed in purging elections of the unequal influences of the celebrated, the well-connected or the wealthy? Restricting one group would just magnify the influence of others.

Many complaints about campaigns seized on by progressives to justify restrictions on speech could be addressed without suppressing 1st Amendment rights. The most widespread complaint is that only the rich get to influence campaigns; the poor and the middle class, the charge goes, wind up frozen out of politics.

Why not, then, provide an income-adjusted tax credit for political contributions? A tax credit of $50, phased out as income rose, would encourage millions of citizens of modest means to donate (collectively) large sums to their favorite candidates. Another concern about money in politics is that political contributors can win economic favors for themselves. Here, too, rules could prevent such favoritism without harming speech. A good example: ensure competitive bidding for all public contracts, which would restrict the actions of government officials, not the rights of citizens.

Applying ordinary free-speech protections to electoral expression ensures that government will still depend on the back-and-forth of open debate, generated by free citizens in all their variety. What’s ultimately at stake in the battle over campaign regulation is the 1st Amendment’s empowerment of civil society over the prerogatives of the state, a virtue — central to our constitutional republic — that liberals once defended.

John O. McGinnis is a contributing editor of City Journal and the George C. Dix Professor in Constitutional Law at Northwestern University School of Law. This piece was adapted from the spring 2016 issue of City Journal.

MORE FROM OPINION

When does free speech become a threat?

That wasn't a Mayan lost city, just another example of the culture of hype

Professors are overwhelmingly liberal. Do universities need to change hiring practices?

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.