What we reveal about ourselves when we talk about disease

- Share via

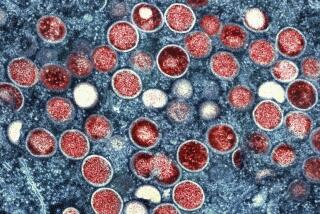

It can’t be just a coincidence that the MPX virus is breaking out in the midst of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, right? These phenomena have people grasping for explanations, like faulting air travel for rapidly spreading contagions around the world.

But disease has been traveling across broad geographies and empires for centuries, since long before air travel. As a historian of infectious disease, I believe that what we’re seeing tells us less about how viruses move and more about the stories we tell to explain disease and how those stories make epidemics visible.

What’s new is our ability to see disease moving and name it. MPX, for example — which is what some health authorities call monkeypox — has existed in Congo and other parts of Africa since the 1970s, but most in the global north gave it little attention. The awareness that rises with the growing presence of MPX in Europe and the U.S. reveals how our reporting of epidemics has been gauged to focus only on certain parts of the world, making the presence of an established disease appear novel because it’s in the U.S.

Counting both uninfected and infected people helps us better understand a pandemic.

The narratives we create about epidemics set the temporal and geographical parameters for when and where epidemics begin and end. Scientists theorize that the COVID-19 virus first spread from Wuhan, China, to Italy and then to Iran and New York, but that trajectory likely tells us less about the virus’ actual movement and more about the available frameworks that made it visible in certain parts of the world.

Similarly, experts posited that the 1918 flu epidemic, whose origins even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dispute, ended in 1920. But that assertion had less to do with the presence of the virus and more with the fact that authorities stopped counting the rate of infection.

Because we have invented sophisticated ways of still seeing it, COVID has not ended. Antigen self-tests as well as government registers that calculate daily infection rates serve as markers that continue to make the disease visible and show it to be widespread, beyond the much smaller numbers of hospitalizations and deaths.

MPX has a similar story. In 2017, for example, an MPX outbreak that infected roughly 200 people in Nigeria seemed to decline in 2018, but, according to Dr. Dimie Ogoina, professor of medicine and infectious diseases at Niger Delta University in Nigeria, officials stopped documenting the number of infected cases, which made it appear the outbreak ended. “Over time, interest and attention to monkeypox just dropped. Surveillance declined,” he told NPR. “The number of cases we’ve had in Nigeria is not a true representation of actual cases because we are not doing sufficient surveillance.”

Doctors and scientists are not the only ones who narrate illness. Patients are increasingly helping the medical profession understand the spread of MPX. It was communities of queer men on social media who shared their stories of infections and helped underscore for scientists that the new outbreak was spreading from close, sexual contact among men who have sex with men. In May, when news of MPX first made headlines in the United States, medical professionals explained that close contact with an infected person could transmit the virus. Sex was not emphasized as a leading factor of transmission until patients’ testimonies illustrated how the virus was spreading and how it presented.

Science at its core is a story. It is not the word of God handed down to Moses. It is a narrative that changes according to new information and new technological discoveries. When epidemics first explode, they appear as uncontrollable and unknowable; medical authorities then try to ease the public’s anxiety by telling a story that imposes logic onto the chaos caused by the outbreak. These narratives might suggest the origin of the epidemic or how to prevent it. Whatever their assertions, these early accounts are subject to revision.

When Ogoina in Nigeria confronted MPX in 2017, he suspected the virus was being transmitted during sex, but Nigerian officials stuck to their story that it was mostly an uncommon infection spread by human contact with infected animals. When MPX began spreading among men who have sex with men in May 2022, the World Health Organization and the CDC were initially reluctant to tell that story, perhaps out of fear of stigmatizing gay men. The story has now shifted away from the cause of the outbreak to how vaccines might control and prevent its further spread.

If we recognize science as both a catalog of technical knowledge about pathogens and a story designed to make sense of epidemics, we can be more open to efforts to revise scientific knowledge or recast a particular explanation. Recognizing how we narrate disease might prevent us from thinking that we are trapped in a never-ending cycle of epidemics. Understanding science as a story will also make us feel less helpless as the deluge of technical information pours in, and we can better question the narratives that are shared.

Jim Downs, a fellow at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University, is the author of “Maladies of Empire: How Colonialism, Slavery, and War Transformed Medicine.” @jimdowns1

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.