- Share via

In Portuguese, my mother’s native tongue, there is one verb, lembrar, that means both to remember and to resemble or remind, the distinction perceived only in context. Many years ago, while I was traveling abroad with an American friend, my mother asked me to call on an old classmate of hers that I had never met. During our visit, he spoke in painstaking English for the benefit of my bewildered companion, remarking repeatedly: “You remember your mother very much.”

It’s true, even more so today. As I grow older, my hair grays, my features sharpen and the differences of color and youth that once told us apart fade away. Almost every time I visited my mother in her assisted living facility, a staff member would tell me how much we looked alike. I remember my mother very much. But in the last couple of years of her life, it was rare that my presence sparked even a glimmer of recognition in her eyes.

Dementia started stealing my mother away before my daughter got to know her. Sometimes forgetful of the simple mechanics required to move her body, my mother was already shaky on her feet when my daughter was born. I delicately but steadfastly did not allow her to hold her granddaughter unless she was safely seated. By the time she took her first steps, my mother regularly forgot her granddaughter’s name. By her second birthday, we had put our house on the market so we could move in with my parents to help care for my mother.

She had reached the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s disease but was otherwise healthy. She was lucky, and so were we, that she could choose to end her life on her own terms before things got worse.

Our family ate dinner together every night. At first, my mother insisted on cooking, but after several charred pots of rice and open flames left unattended, we steered her toward washing vegetables and setting the table. She took delight in watching my daughter master skills — how to cut food, how to string words together to form a sentence — that she herself was forgetting. Her joy was bottomless, as she could not remember from one day to the next what developmental leap we had all witnessed the night before. Soon my mother began dropping plates, spilling drinks and breaking glasses on a regular basis. My daughter quickly learned another fundamental task in our household — how to step around shards of glass while fetching the broom and dustpan.

After dinner, I got my mom ready for bed. I helped her use the toilet, brush her teeth and wash her face. I’d change her into the faded, flowered cotton nightgowns she favored and then lie down beside her. We talked and held hands until she closed her eyes. Although by then her fine motor control was fickle and she struggled to find words, my mother always excelled at mimos — gestures of affection.

One night, she reached out to cup my face with a sure hand. Tears at the corners of her eyes, her fingers traced my features, lingering on the strong bridge of my nose that she referred to as my inheritance. She held my gaze and whispered, low but clear, “You are the best thing I have ever made.” Arrested by her sudden eloquence, I managed only to kiss her hand in response before she fell asleep.

I closed the door to my parents’ bedroom behind me and walked down the hallway to find my daughter still awake. Taking over for my husband, I helped her use the toilet, brush her teeth and wash her face. Together we found her favorite R2-D2 pajamas buried among the covers of her unmade bed. After reading a couple of picture books, we turned off the lights and cuddled. Settling into what had become a familiar routine, I held her hand and told stories of her grandmother’s courage and competence — hallmarks of immigrant motherhood.

I’m outspoken, ready to burn down the patriarchy, and I am my mom’s daughter, even if she can’t see it.

There were big adventures: how Grandma, as a young woman, traveled alone thousands of miles from Portugal by steamship and train to Michigan, a place so cold she had to learn a new way of walking, picking her way across the ice toward a different life. Then there was the more mundane but no less extraordinary: how after long days and an arduous commute, Grandma would conjure — from leftovers, copious garlic salt and sheer determination — a table full of fragrant food and rowdy conversation every night. I did not realize there were tears streaming down my cheeks until I felt my daughter’s hot little hands wiping them away. She traced the arch of my brow, the hook of my nose and told me how much she loved me.

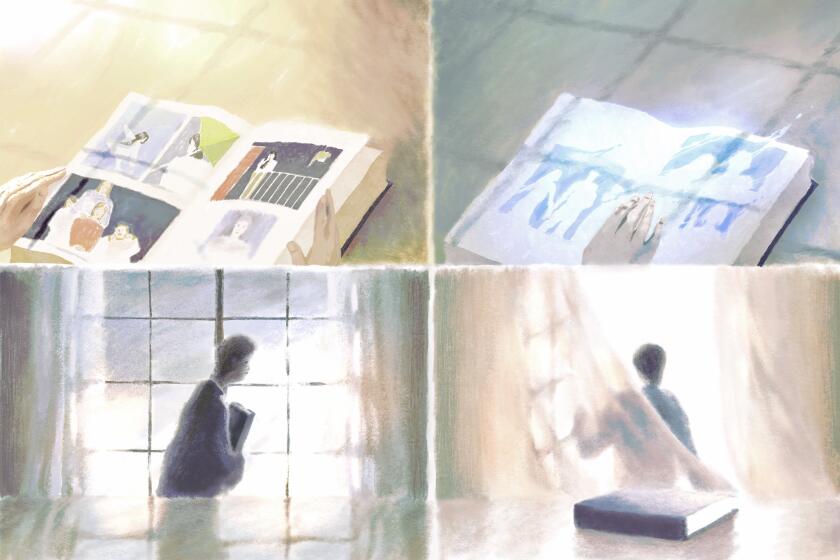

When my daughter was a newborn, the long hours I spent immersed in her care caused me to lose my sense of self in an almost palpable way. Those early days, when I caught a glimpse of my reflection in the mirror, I was often startled to see my own face, and not my daughter’s, staring back. Against the backdrop of my mother’s rapidly deteriorating condition, I understood my momentary confusion as a measure of how the seemingly endless ministrations of care can make us forget who we are. Over time, my daughter’s particular brand of unabashed affection has taught me that each mimo I pass down to her is actually an act of remembering.

My mother died in December, after enduring dementia’s merciless progress for more than a decade. This month, my daughter bounded into her 11th year. In the way that children seek themselves in their families, she asks how she is like her grandmother more frequently since her passing. As I answer, they both come into sharper focus. Choosing from an ever-growing list of traits, I tell my daughter she inherited her grandmother’s quickness of mind and temper; her magnetic warmth; her sharp tongue; her joyful resourcefulness; her fierce curiosity and compassion; her very small feet and very dark eyes; her dusky laugh that tickles others into joining.

I do remember my mother, and my daughter will too.

Julia Figueira-McDonough is a caregiver and attorney in Los Angeles.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.