- Share via

My father, Jawdat Bseiso, was 23 when everything changed.

As the favorite son of Mahrous Mustafa Bseiso — one of the largest landowners in southern Palestine — he was being groomed to inherit our family’s legacy. My grandfather was a prominent businessman in Beersheba, a thriving Palestinian city where Muslims, Christians and Jews once lived together in peace.

Then came May 15, 1948. Palestinians know it as the Nakba — the Catastrophe. That day, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, including my entire family, were forcibly displaced during the founding of the state of Israel. Our lands, homes and businesses were seized, and we were labeled “absentees” even though we had been violently expelled and our properties expropriated.

Overnight, my family became refugees. Our home, along with hundreds of thousands of acres of our land in Beersheba and elsewhere, was taken and handed over to the Israeli state. The property was listed under that government’s Custodian of Absentee Property, but we were never absentee: We were driven out and not allowed to return and regain our family properties.

I was born in 1962 in Al Bireh, near Ramallah in the West Bank. My family eventually immigrated to the United States and became citizens. Like many other refugees, my parents shielded us from the past. My father rarely spoke of what had happened. He carried the pain silently, his eyes always seemingly fixed somewhere else, trapped between memory and loss.

In America, I faced the usual immigrant struggles: racism, bullying and the pressure to assimilate. To protect myself, I turned to wrestling and martial arts. As an adult I eventually made a career in the music industry, but even then I felt I had to hide. Instead of working under my given name, Adel, I went by Eddie, then Edvardo, and finally Vardo Bissiccio, leaving my Arabic name out of my career. Success came, but the hunger for truth remained.

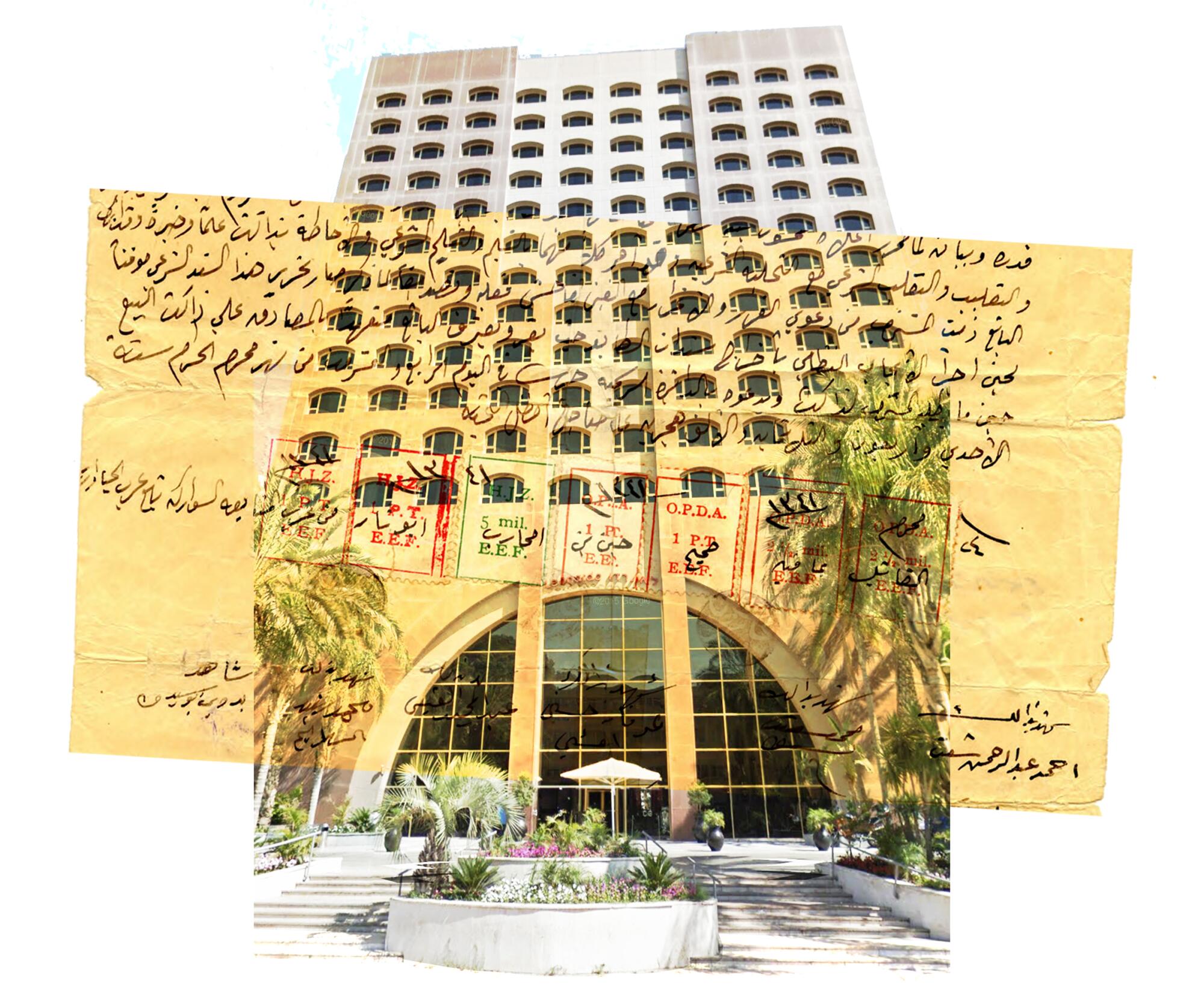

I spent years searching for answers: what we had lost, who we really were and what had been stolen from us. Long after my grandfather and father passed away, I kept searching, and I found answers — a trove of evidence such as land deeds, tax records, sales contracts and letters of correspondence, painstakingly gathered and verified. They tell a story of prosperity before displacement, and of legal rights denied. They also preserve the legacy of my grandfather, a man who turned the desert into gardens, farms and industry around Beersheba in the early 20th century.

Although this search began from a personal yearning, I realized the resulting collection could be valuable to many others. Indeed, when I invited scholars to verify and assess the files, we concluded that the Bseiso family archive is the largest known collection of original documents from a single Palestinian family, detailing legal land ownership before the 1948 Nakba.

In 2019, I began digitizing the records, and Columbia University eventually agreed to house the collection within its modern Arab studies program. In 2025, we launched BFArchive.org, making Palestinian history more accessible to scholars, journalists and the public.

May 15 marks the 77th anniversary of the Nakba. Our documents now serve as legal and historical evidence not only of our own story but also of a broader pattern of dispossession.

None of this is meant to challenge the existence of the state of Israel or to erase any other group’s history. Our goal is justice. We aim to set the record straight and pursue compensation for the billions of dollars’ worth of property that was unlawfully taken from our family and from so many others.

The global conversation is changing. Millions now march in support of Palestine. Nations around the world are recognizing Palestinian statehood and the right of return. What was once hidden is being brought to light. A “black swan” moment — a tipping point for justice — is approaching.

The scale of what was taken from us is staggering: land, legacy, opportunity. But behind those material losses lies something deeper, a history, a rightful place in the narrative of the land we once called home.

For decades, I’ve preserved not just documents but stories. Oral histories passed down from my grandfather, my father and our elders speak of a time before the Nakba — of community, coexistence and peace. They also bear witness to what came after: exile, erasure and ongoing injustice.

My family’s archive exists to preserve those truths and to make them impossible to ignore.

Adel Bseiso, an American Palestinian music producer, lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

- The author argues that Palestinians deserve reparations for properties unlawfully seized during the 1948 Nakba, citing their family’s archive of land deeds, tax records, and legal documents as evidence of systemic dispossession.

- They emphasize the intergenerational trauma of displacement, describing how their family’s prosperous legacy in Beersheba was erased overnight, transforming them into refugees barred from reclaiming their homes.

- The article frames reparations as a path to justice rather than a challenge to Israel’s existence, highlighting global shifts toward recognizing Palestinian statehood and the right of return as part of a broader “tipping point” for accountability[3].

- By digitizing and publicizing their family’s archive through Columbia University and BFArchive.org, the author seeks to counter historical erasure and provide scholars with tools to reconstruct suppressed Palestinian narratives[2].

Different views on the topic

- Critics argue that reconstruction and aid efforts in Gaza should prioritize immediate humanitarian needs over historical reparations, with international donors often sidestepping direct financial accountability for Israel despite its legal obligations[4].

- Some Israeli officials and analysts frame military escalations, such as the 2025 airstrikes, as necessary for national security, linking ceasefire collapses to domestic political pressures like budget votes and coalition stability rather than colonial legacies[1][3].

- Legal challenges at the ICC and ICJ, while advancing accountability for wartime conduct, face opposition from states questioning the courts’ jurisdiction over sovereign military actions and their potential to complicate peace negotiations[1][4].

- Skeptics of reparations often dismiss Nakba narratives as politically motivated, advocating instead for economic investments in Palestinian territories without addressing underlying claims of property restitution or systemic displacement[2][4].

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.