Must Reads: Gov. Brown says fallout from Trump quitting Paris accord is ‘far more serious than anyone is saying’

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — His promised coal renaissance sputtered. Rollbacks of environmental protections are tangled in court. Even automakers aren’t on board for his push toward heavier-polluting cars.

But even so, a year after President Trump pulled out of the landmark Paris accord on climate change, the struggle to contain global warming has grown considerably more complicated without the prodding and encouragement once provided by the U.S. government.

And though many in the climate movement hope progress toward cutting emissions can continue despite Trump’s retreat, there are growing doubts about reaching the Paris agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, if Washington does not re-engage soon.

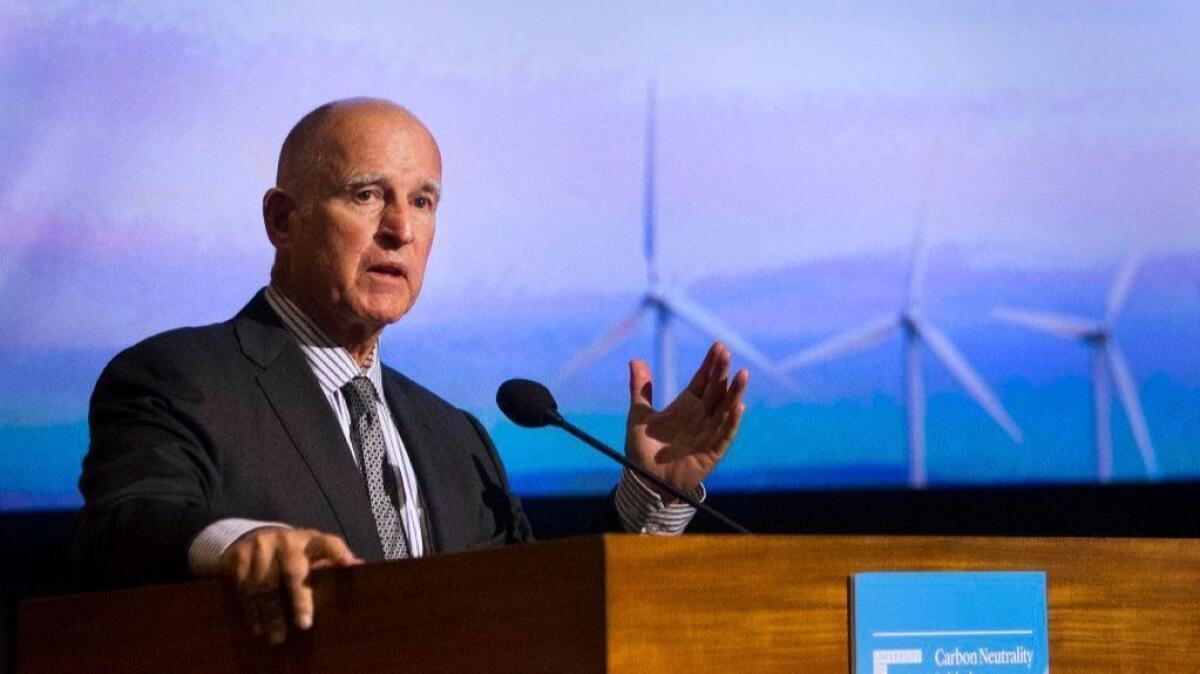

In an interview, Gov. Jerry Brown acknowledged the hope felt by many climate activists because of efforts from states like his and by private companies. But he also said the world is only just beginning to feel the environmental harm inflicted by the Trump administration.

“He has set in motion initiatives that will cause damage,” Brown said, comparing the planet under Trump’s climate policies to a person who has just fallen from the top of the Empire State Building. “You are falling down four stories, but have 80 to go,” he said. “Maybe you are not damaged yet, but it is certain you will die.”

The governor said his overriding concern is that global progress has stalled. “This is real,” Brown said. “It is far more serious than anybody is saying.”

Yet even in these dark days for climate action, plunging natural gas and renewable energy costs, as well as the grit of state and local leaders determined to carry on without Washington — and to fight it in court — have bought the movement some time.

Some activists are increasingly optimistic that they can wait this administration out. They are diligently crunching numbers and preparing reports to unveil at the global climate summit Brown is hosting in California in September. That’s when new benchmarks will be proposed for getting the nation back on track for meeting its Paris commitments.

And in many ways, Trump has proved far less competent at dismantling climate action than initially feared, they say.

“Teddy Roosevelt talked about speaking softly and carrying a big stick,” said Nigel Purvis, a climate negotiator during the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations and chief executive of the firm Climate Advisers. “Donald Trump is tweeting loudly and carrying fiddlesticks. The level of damage is not as much as one might have thought given all the tweeting and speeches.”

Coal plants have continued shutting down at a brisk pace since Trump took office. The costs of renewable energy continue to fall, even after Trump slapped tariffs on foreign-made solar panels crucial to the industry’s growth. Led by California, states representing 40% of the U.S. population are pushing ahead with innovative strategies to drive their emissions down, and are on track to meet their states’ benchmarks under the Paris agreement.

The group, called the U.S. Climate Alliance, on Thursday rolled out a fresh set of actions it will take to keep the U.S. moving toward its Paris commitments. They include policy innovations that put the coalition — which collectively represents an economy larger than most industrialized nations — at the forefront of the climate movement. The alliance has grown to include three states with Republican governors.

In yet another sign of how much of the nation is moving in the opposite direction as the Trump administration, McDonald’s has joined such companies as Walmart and Citigroup in pledging to abide by the Paris agreement. It is a heavy lift for a company serving 69 million people a day — one that will mean upending its supply chain for beef and packaging. The emissions it will cut by 2030 are roughly equal to the amount of greenhouse gasses 32 million passenger cars create in a year.

It’s all encouraging, said Marc Hafstead, an economist at the Washington think tank Resources for the Future, but it falls far short of getting the country where it needs to be. “If we are going to take this target seriously, we need federal action,” he said. “There is still time. We can still do something in 2020 or 2021 or after.” The more time that goes by, the bigger that something must be. Hafstead anticipates a national policy of pricing carbon will be essential.

Such policies are proving politically challenging even in the states most bullish on climate action. California is the only one that has achieved economy-wide carbon pricing so far. Efforts in other Western states have fizzled. Even if a move afoot to impose a California-style carbon pricing plan in several New England states succeeds, that would still leave 93% of the nation’s emissions free of such levies.

There is another big problem states are finding themselves hard-pressed to tackle: automobiles. Even the aggressive Obama-era fuel economy standards the Trump administration is trying to scrap do not go far enough in reducing vehicle emissions, which recently became the nation’s biggest contributor to climate change, surpassing power plants.

States are trying to do their part by building vast charging networks that will encourage drivers to move into electric vehicles. But even as other nations set timelines for banning combustion engines, sales of zero-emissions vehicles in the U.S. are minuscule.

“How do you achieve this massive shift in consumer and automaker behavior that gets the majority of vehicles sold in next few years into the zero-emissions category?” said Kate Larsen, a director at Rhodium Group, a research firm that tracks the progress nations are making in meeting climate goals.

“No one has a clear idea of how to do that on the time frame we need.”

Larsen said that by 2030, at least half the vehicles sold — and possibly as many as 75% — would probably need to be zero emissions to keep global warming from exceeding the 2-degree Celsius mark. But the U.S. is nowhere near on track to hit that goal. Current projections show that only 9% of the cars on the road will be zero emissions in 2025.

“That would require a huge ramp-up for the next five years,” Larsen said.

Getting there without federal action could be impossible. The same goes for placing new controls on industrial emissions that climate analysts say will be essential to containing global warming.

Even as he leads the push to do as many of these things as possible in the absence of federal leadership, Brown warns it won’t be enough if Washington does not get back on board.

But Brown sees one tiny silver lining in an administration full of climate denial: the White House retreat has made for a lot of headlines that have galvanized the climate movement.

“This conflict of Trump versus Paris, Trump versus climate change, acts with a catalytic force that is increasing intensity of this issue and actually encouraging climate action,” Brown said. “We are not going to meet the [Paris] goal on the track that we are now on. But this track can be altered. With sufficient political change, we can get back on track.”

More stories from Evan Halper »

Follow me: @evanhalper

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.