Gov. Gavin Newsom uses the power of appointments to shape government in his image

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Gov. Gavin Newsom highlighted a highly significant but less visible power of his office in his first State of the State speech earlier this month: selecting appointees who can reshape California government in his image and help deliver on his ambitious policy agenda.

After condemning the lackluster oversight of a $77-billion California bullet train plagued with cost overruns, Newsom punctuated the call for change by announcing he was appointing one of his top economic advisers to take the helm of the High-Speed Rail Authority.

For the record:

6:30 a.m. Feb. 27, 2019A previous version of this article identified former Gov. Gray Davis’ appointments secretary as David Yamaki. His first name is Michael.

The Democratic governor also picked a new chairman, Joaquin Esquivel, a former assistant secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency, for the Water Resources Control Board to bring “balance” to state water policy, which has been hamstrung by conflicts among farmers, cities and environmentalists.

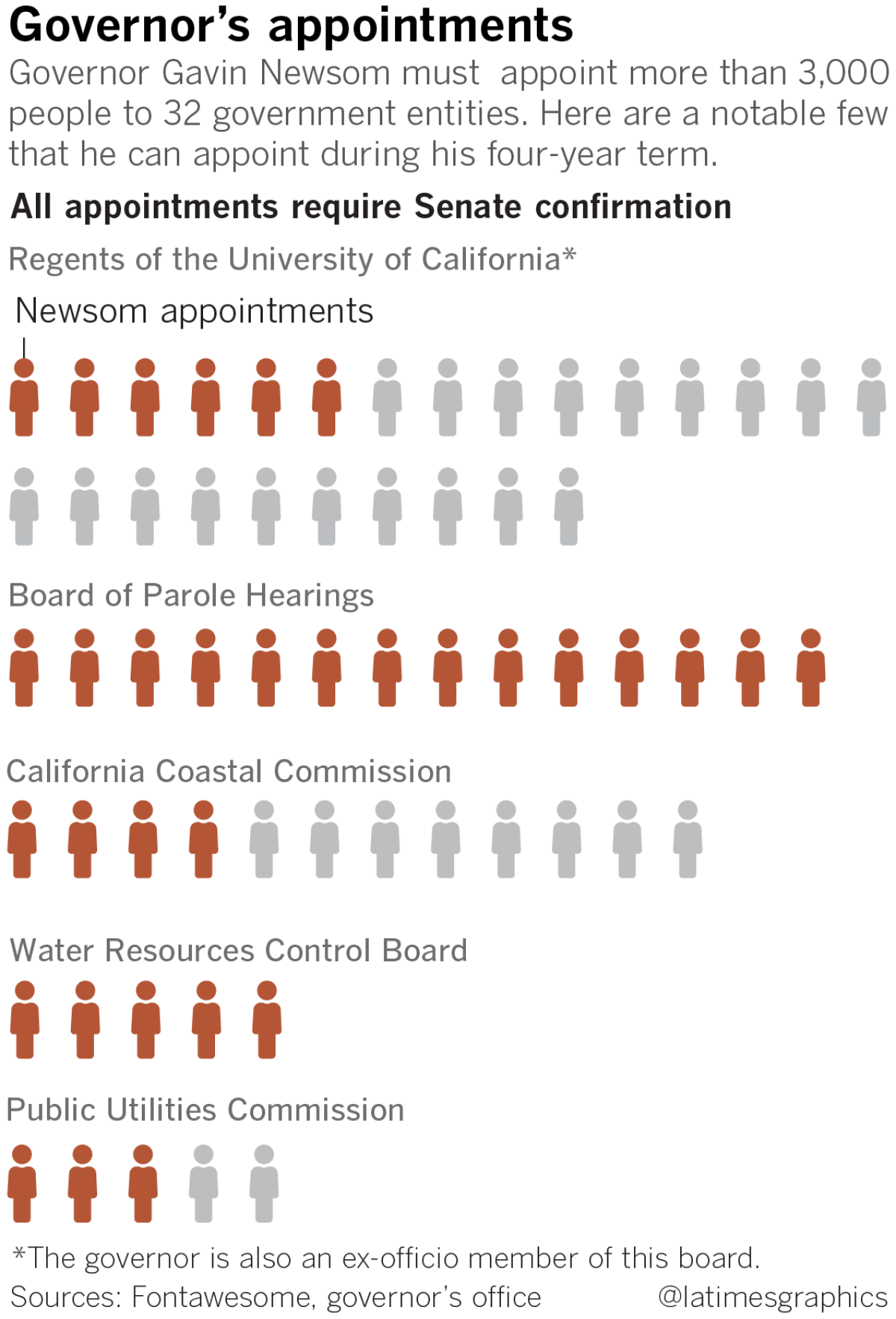

Over the next four years, Newsom will have the opportunity to appoint more than 3,000 people to 32 government entities.

That includes 12 of the 14 voting members of the state Air Resources Board, the bulwark for California’s tough vehicle emission standards. And six members of the University of California’s 25-member Board of Regents. Newsom can also replace nearly half of the High-Speed Rail Authority, a third of the voting members of the California Coastal Commission and the entire state parole board.

Most appointees toil away on boards that rarely pique public interest. But that can change quickly: If drought and wildfire strike or college tuition and gasoline prices spike, boards tasked with overseeing those issues are thrust into the spotlight.

“Only in times of crisis … do most people realize how critically important these appointments are,” said Richard Frank, director of the California Environmental Law and Policy Center at UC Davis.

Newsom declared in his State of the State address that his economic development director, Lenny Mendonca, was being appointed to the High-Speed Rail Authority and was his “pick for the next chair.” He was later unanimously approved by the nine voting members of the board as chairman.

The move came eight years after Gov. Jerry Brown, also in an effort to have the board get its “act together,” appointed the authority’s former chairman, Dan Richard, who resigned from the board last week.

The power of a governor’s decision-making on appointments became clear during California’s recent five-year drought, when the State Water Resources Control Board imposed stringent water-use restrictions on urban suppliers and farmers throughout the state.

Newsom also made his mark on the water board by removing Felicia Marcus as chair.

A former regional director for the Natural Resources Defense Council, Marcus clashed with San Joaquin Valley irrigation districts and Northern California water authorities in December when the board voted to curtail river diversions to help restore the state’s struggling rivers and fish populations.

Mike Wade, executive director of the California Farm Water Coalition, said it was “difficult and disappointing” to have a board that appeared to shun local water users, including both cities and farmers. He praised Newsom’s decision to appoint Esquivel, a current board member, as the new chairman.

Laurel Firestone of Sacramento, co-director of the Community Water Center and an advocate for environmental justice, also was appointed to the board by Newsom.

“This affects 40 million people around the state. They can affect entire regional economies,” Wade said.

Among the most scrutinized of Newsom’s appointments will be those to the five-member California Public Utilities Commission, which oversees utilities and approves rate increases. The agency has been criticized for failing to adequately address the thousands of wildfires ignited by power lines in recent years.

The recent bankruptcy filing of California’s biggest utility, Pacific Gas and Electric, will also fall into the commission’s lap. The utility filed for bankruptcy in January following the deadly wildfire that decimated the Northern California town of Paradise, opening PG&E up to billions of dollars in potential legal liability. The commission will need to approve any reorganization plan that involves raising electricity rates, authority critical to protecting the interests of Californians.

In January, Newsom appointed former Agricultural Labor Relations Board Chairwoman Genevieve Shiroma to the board. And he’ll have the opportunity to appoint a board majority when the terms of two other members, including PUC President Michael Picker, expire in 2021.

Newsom also has a powerful tool in his appointments to the state Board of Parole Hearings, which could allow him to fulfill his promise to refocus the state corrections system on rehabilitation and, as he said in his inaugural address in January, to “continue the fight against over-incarceration and overcrowding in our prisons.”

The 14-member parole board is poised to reclaim power it hasn’t had in more than a generation. Proposition 57, approved by voters in 2016, will give sweeping new authority to state officials to release prisoners before they’ve served their full sentences. For years, parole board members would often deny prisoners early release based on the severity of a criminal offense rather than whether they would pose a safety risk if set free.

Lenore Anderson, executive director of the Californians for Safety and Justice, wants to see Newsom appoint members to the Board of Parole Hearings who have expertise in mental health, drug treatment and helping inmates reenter society.

“We used to be a state with mandatory sentences and warehouse prisons, where punishment was the only focus,” Anderson said. “We’re in an era of change. The public wants rehabilitation. They want to know that people are being prepared for release.”

Most of Newsom’s executive appointments and his selections for critical regulatory boards require confirmation by the state Senate.

Along with agency secretaries and other top executives, there are dozens of state boards and commissions with openings — most positions are unpaid but a few come with lucrative salaries attached.

According to the California state Controller’s office, members of the Public Utilities Commission were paid nearly $146,000 each in 2017 and commissioners on the Board of Parole Hearings received $144,000 — both are full-time jobs. In contrast, members of the California Coastal Commission, which meets 11 times a year, are paid $100 for every day they work, plus travel expenses.

Newsom announced shortly after taking office that he would ensure his appointments reflected the diversity of California in regard to geography, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, professional experience and disability status.

California Women Lead, a group that advocates for women to be appointed in state government, offered advice to former Gov. Jerry Brown when he chose many of his appointees, collecting and sorting through resumes to find good candidates, according to the organization’s former executive director, Rachel Michelin.

“You’ve got a lot of progressive groups looking at California, thinking they can have an impact on progressive policies,” Michelin said. “Especially with healthcare reform being such a big topic. He can put people on all those boards.”

Michelin, an appointee to the state Board of Optometry, said most Californians have no idea how much influence the panels have.

“We pass regulations and policy all the time, and no one pays attention to what we’re doing,” she said.

Los Angeles attorney Michael Yamaki, who was the appointments secretary for former Gov. Gray Davis, said the highly paid appointments have always been the most coveted — including by deposed elected officials looking for a paycheck.

“That happens when politicians get termed out or voted out of office,” Yamaki said. “They come begging to the governor: ‘I need a job.’”

Yamaki said serving as a governor’s appointments secretary can be a tricky, sometimes perilous job.

Even appointments to the dental board can generate controversy, he said.

Yamaki said he dealt with a rift between holistic dentists — who opposed the use of amalgam fillings because they included mercury — and traditional dentists, who at the time favored those fillings because they were affordable to patients and were covered by insurance.

“There was a big fight over that,” he recalled. “So I had to pick people that were not so polarized that they couldn’t cooperate.”

Not only are appointment secretaries and their bosses heavily lobbied by special interest groups, but they must be careful to pick appointees who haven’t done something in the past — or won’t do something in the future — that makes the governor look bad.

“Don’t do anything to embarrass us,” Yamaki said he told those selected.

Sometimes, however, an appointee’s tenure lasts longer than that of the governor who selected him or her, making it hard to manage the potential for embarrassment

Consumer groups protested loudly in 2002 when then Gov. Gray Davis nominated Michael Peevey, a former Southern California Edison president who made millions of dollars during the state’s failed deregulation effort, to the PUC in an attempt to make the five-member commission more moderate. Groups including the Foundation for Taxpayer and Consumer Rights in Santa Monica accused Davis of putting the interests of the power industry ahead of consumers.

California voters recalled Davis from office the next year, in part because of the state’s electricity shortages in 2000 and 2001.

Peevey, who stayed on the PUC another decade after he was reappointed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, stepped down from the board in 2013 after the state launched an investigation into allegations of improper back-channel communications between him and PG&E officials.

At the time, the utility was under scrutiny for a San Bruno pipeline explosion in 2010 that left eight people dead.

Twitter: @philwillon

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.