Q&A: The Constitution gives no road map for an impeachment inquiry. Here’s what it could look like.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Amid allegations that President Trump abused his power by pressuring Ukraine to investigate one of his political rivals, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) opened a formal impeachment inquiry.

Trump has acknowledged that he asked Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenesky to open investigations into Biden and his son Hunter, who served on the board of a Ukrainian gas company. At the time of the July 25 phone call in which Trump asked Zelensky for this “favor,” the U.S. president had also put a hold on nearly $400 million in aid to Ukraine.

Those actions — first disclosed in a whistleblower’s complaint — are now at the center of the House impeachment inquiry. Trump insists the withholding of the aid was not related to his request that Ukraine investigate one of his leading political rivals in 2020.

Though three former presidents have faced serious impeachment efforts, and two were impeached, the road ahead is only loosely laid out by the Constitution.

Here’s a look at what’s expected to happen next.

How does the House impeach a president?

Beyond saying it should be based on “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors,” the Constitution provides surprising little information governing how to impeach a sitting president.

Just two presidents, Bill Clinton and Andrew Johnson, have been impeached. President Richard Nixon resigned from office in 1974 when it became clear there were enough votes in the House to impeach him and in the Senate to remove him from office.

Each was handled differently. In the Clinton and Nixon cases, the House Judiciary Committee held lengthy investigations and then recommended articles of impeachment to the full House. Johnson was impeached a few days after firing his Secretary of War in violation of the Tenure of Office Act, which Congress had passed to keep him from changing the members of his Cabinet without their permission.

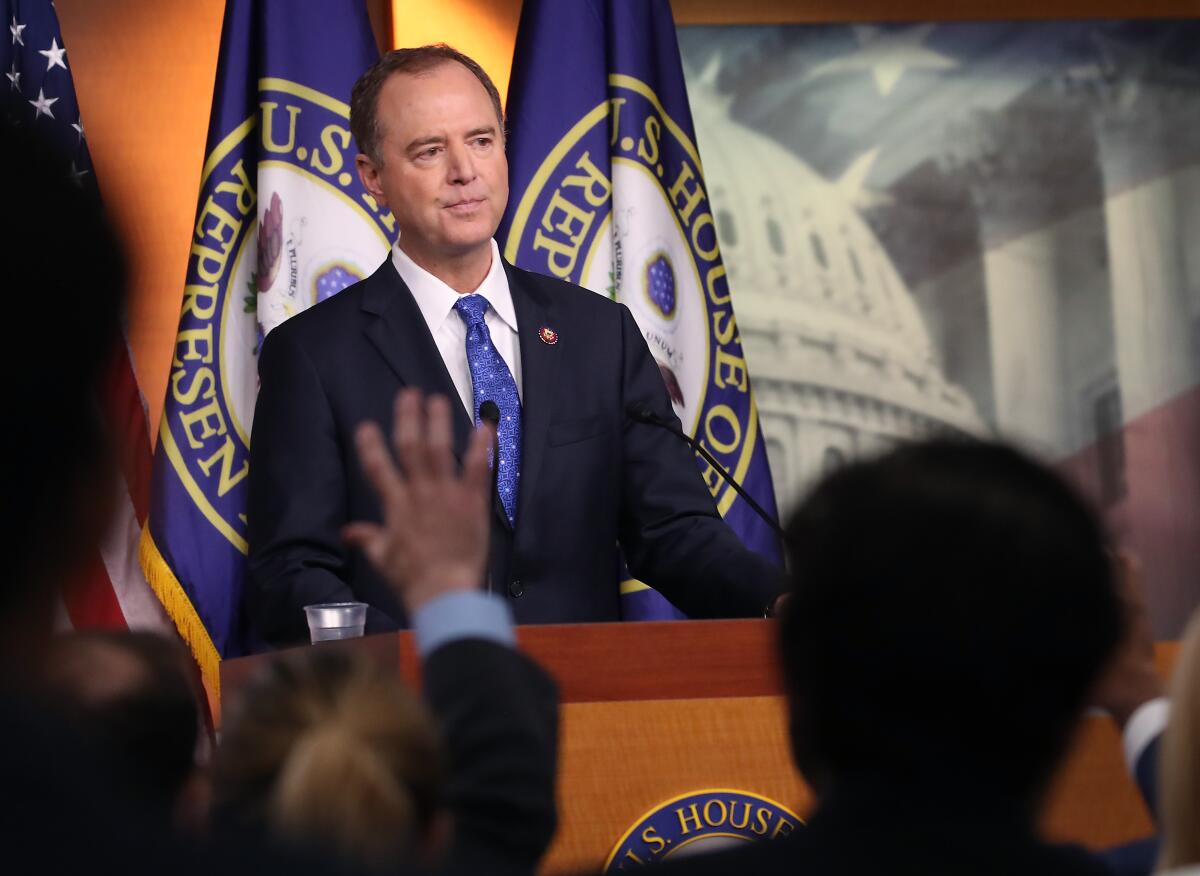

Pelosi has announced that House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank) will lead an investigation into the whistleblower’s allegations, and along with five other committees, feed information about potential articles of impeachment to the House Judiciary Committee, which will then decide whether to forward any to the House for a vote.

If a majority of representatives supports even a single article, the president is impeached.

Doesn’t the House have to vote to open an impeachment inquiry?

This has been the subject of much dispute. The House voted to open an inquiry into Nixon and Clinton, but when the House impeached President Andrew Johnson in 1868, it did not.

Pelosi has indicated she doesn’t see such a vote as being necessary. Republicans meanwhile are using the lack of a vote to argue the inquiry isn’t legitimate.

Just because the House voted to open an inquiry in the past doesn’t mean it must always do so, Brookings Fellow Margaret L. Taylor said.

“There’s no real technical reason for a full House vote,” Taylor said. “The Constitution does not prescribe how the House impeaches.”

Does this mean House Democrats are done with their other investigations into Trump and his administration?

No. The Financial Services Committee will continue seeking the president’s financial records from Deutsche Bank. The Ways and Means Committee is still seeking copies of Trump’s tax returns from the IRS. Judiciary will keep looking at Russian attempts to interfere with the 2016 election.

But at this point, any articles of impeachment are expected to focus on Ukraine and the whistleblower complaint.

Can the White House block the Ukraine investigation?

The Trump administration could try, and there have been some indications that it will resist the House inquiry. In other House investigations, the administration has refused to hand over documents or comply with subpoenas. When officials have appeared to testify before Congress, many have asserted they are covered by executive privilege and aren’t able to answer questions.

But the stakes are much higher in an impeachment inquiry. White House attempts to stonewall the House impeachment investigation could themselves become grounds for impeachment. .

“Now instead of Congress saying pretty please comply with our subpoenas, they can demand that people provide this testimony, and if they refuse to do so, use that refusal to do so by the White House as the basis for additional articles of impeachment,” said Susan Hennessey, a senior fellow at the nonpartisan Brookings Institution.

Congress used Nixon’s refusal to hand over documents and audio as the basis of its third article of impeachment against him.

The House could also potentially use its so-called inherent contempt power to compel the administration to comply. Once a commonly used congressional power in which the House arrests or fines people who won’t comply with subpoenas, it hasn’t been used in 84 years. More recently the House has asked the Justice Department and the courts to uphold their right to gather information. Such efforts have proved fruitless under the Trump administration.

“The efforts by the White House to intimidate, to prevent access, to prevent us from doing our investigative responsibilities is a violation of the Constitution. So we should be exercising our rights under inherent contempt,” Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Hillsborough), an Intelligence Committee member, said.

What will be in the articles of impeachment?

That’s fluid and it’s way too early to say for sure. Generally it’s expected that any articles could include obstruction of Congress, obstruction of justice and abuse of power.

Clinton was impeached on two articles: lying under oath and obstruction of justice. Nixon faced three articles: obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress. Johnson was impeached on 11 articles.

Hennessey said Democrats have to look for two things as they decide what to include: unambigously impeachable conduct and unambiguous evidence. That means it’s unlikely articles of impeachment will include Trump’s behavior before he was president or anything the House has been investigating since Democrats took power in January that is embroiled in a legal battle.

It also is unlikely to include Democrats’ frustration over immigration and other policy disagreements, or most of what Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller III found in his report into Russian interference in the 2016 election.

“Impeachment is not an airing of any and all grievances against the president,” Hennessey said.

But that might be difficult to balance, she said, because Democrats will not want to appear to be condoning other behavior they’ve been investigating.

“Impeachment is the mechanism by which Congress says what is acceptable and what is not acceptable,” Hennessey said. If something isn’t included, “you risk sending the message to future presidents that this other stuff is not impeachable conduct.”

Once the House votes, then what?

In case high school civics feels like a long time ago, here’s a reminder. Impeachment itself does not mean removal from office.

Think about impeachment as the House voting to bring charges against the president, not unlike how a grand jury might hand up an indictment.

It then becomes the job of the Senate to hold a trial and determine whether to convict the president and remove him or her from office.

A team of representatives, known as managers, play the role of prosecutors. The president gets to have defense lawyers, and the Senate serves as the jury. (Several Republican senators have already claimed they cannot answer reporters’ questions about the allegations against Trump because they are potential jurors, though that did not stop GOP lawmakers during the Clinton impeachment.)

If at least two-thirds of the senators find the president guilty, he is removed, and the vice president takes over as president. There is no appeal.

This has never happened. Both Clinton and Johnson were not found guilty and remained in office. Nixon resigned when it became clear that he had lost the support of fellow Republicans and was going to be removed.

Is the Senate required to hold a trial?

Kind of.

Under Senate rules, if the House votes to impeach, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said, “I would have no choice but to take it up.” Speaking on CNBC Monday, he added, “How long you’re on it is a whole different matter. But I would have no choice but to take it up, based on a Senate rule on impeachment.”

That could take several different forms. It would take just a majority vote of senators, for example, to bring the articles up for consideration and then simply dismiss them without having a complete trial. Also, it’s always possible for the Senate to just change the existing rules.

What McConnell decides to do may depend on public opinion, and whether vulnerable Republican senators feel like they can defend their votes enough at home to be reelected.

When will this be over?

Pelosi wants the investigation to move “expeditiously.”

Democratic leaders have hinted that it will take weeks, a few months at most. They don’t want to drag this out too long and lose public interest.

Democrats might want to file articles of impeachment by the end of the year to lessen the appearance that they are trying to influence the 2020 presidential election, and to reduce how much time their 2020 nominee has to spend time talking about it.

“At this point my view is we need to either go forward with impeachment — or not go forward — by the end of this year,” said Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance), a member of the Judiciary and Foreign Affairs Committees. “At some point the American people will be able to remove or not remove [the president] in November. The closer you get to an election the less sense it makes to do an impeachment process,”

John Hudak, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, said it’s too early to know which party will politically benefit from the inquiry and which will be hurt.

“The next five to eight weeks are probably going to tell us a lot more about the 2020 election that the last three years have,” Hudak said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.