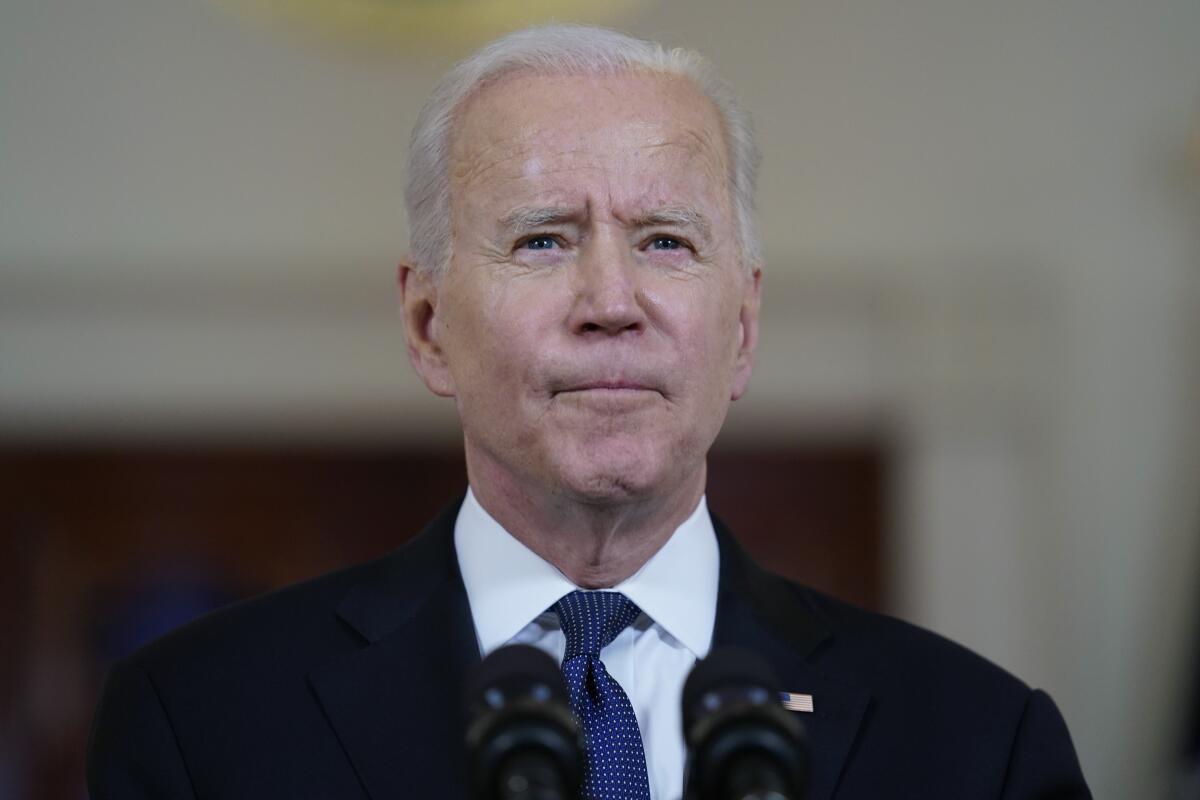

As Biden meets South Korean leader, Mideast again distracts him from focusing on Asia

- Share via

WASHINGTON — President Biden hosts South Korean President Moon Jae-in at the White House on Friday for his second in-person meeting with a foreign leader, and the second with a leader from Asia, a bit of scheduling that underscores his eagerness to shift U.S. foreign policy priorities to the Indo-Pacific region from the war-torn Middle East.

Yet like a recurring scene from a “Godfather” sequel, the Mideast conflicts keep pulling a U.S. president back.

Preparations for the summit with Moon have been overshadowed by nearly two weeks of intense violence between Israelis and Palestinians and rising pressure on Biden to intervene to help end the fighting.

Even if the cease-fire announced Thursday takes hold, the renewed hostilities between Israel and the militant group Hamas have signaled that Biden — like President Obama — won’t find it easy to execute his Asia pivot to contain a rising China after decades of U.S. involvement in the Mideast.

“The administration has made it clear that it strongly believes the Asia-Pacific region is vital to U.S. national interests and wants to strengthen its focus and influence there,” said Frank Aum, a former Pentagon official and now senior North Korea expert at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

A pivot to Asia “will be more difficult” if the Palestinian-Israeli conflict continues, Aum said. Yet, he added, the Biden administration has already shown by its handling of several domestic and overseas crises that it is able to “walk and chew gum at the same time.”

Other issues aside, Biden and Moon plan to use their meeting to emphasize the strong economic and security relationship between their countries, especially after the last four years, in which former President Trump de-emphasized the two nations’ alliance in his zeal to open relations with North Korean autocrat Kim Jong Un.

Biden probably will announce new economic commitments from South Korean companies to invest in the United States — several CEOs accompanied Moon — and to expand bilateral trade.

Additionally, South Korea could announce a more ambitious goal for the reduction of carbon emissions by 2030, something the Biden administration and Biden’s special climate envoy, John F. Kerry, have been pushing Seoul to do. Under the Paris climate agreement of 2015, South Korea pledged a 24% reduction in emissions by 2030; the U.S., by comparison, has pledged a 50% reduction in the same period.

Moon, who is in the final year of his term, is likely to leave Washington with a commitment from Biden to help South Korea bolster its supply of COVID-19 vaccines. But persuading the U.S. president to take additional steps to normalize relations with North Korea will be a heavier lift.

Biden’s top Asia specialist, Kurt Campbell, has said the administration wants to build toward the goal of getting North Korea to give up its nuclear weapons, as outlined in the statements Trump and Kim signed after their first meeting in Singapore in June 2018. Yet the White House is unlikely to go as far as Moon would like and declare an official end to the Korean War, which would amount to a major concession to Kim.

“Our goal remains the complete denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, with a clear understanding that the efforts of the past four administrations have not achieved this objective,” said a senior administration official who briefed reporters about the summit this week on condition of anonymity.

Biden’s policy toward North Korea, the official continued, “will not focus on achieving a grand bargain, nor will it rely on strategic patience” — the phrase for the Obama administration’s policy of engaging with Pyongyang even as it imposed sanctions for the North’s transgressions. The official described “a calibrated, practical approach that is open to — and will — explore diplomacy” with North Korea, “to make practical progress that increases the security of the United States, our allies, and our deployed forces.”

Some analysts don’t see that explanation as much different from the policies of Biden’s predecessors, but it suggests that North Korea may be less of a priority for Biden.

“This seems like this policy is designed as a holding action so they can say they are doing something on North Korea while they’re concentrating on other things that they feel are more pressing,” such as policies on China, global warming and domestic economic recovery, said Sue Mi Terry, a Korea expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. “There’s just not going to be a significant breakthrough. And I think the Biden administration knows that.”

David Maxwell, a former U.S. Army officer in Asia and now a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said Biden will have no choice but to keep North Korea high on the agenda, given its ongoing threat to South Korea, its nuclear proliferation, global cyberattacks, weapons shipments to conflict zones and other illicit activities.

“That little country has impact around the world and impact on U.S. foreign policy,” Maxwell said. “To his credit, Biden has demonstrated an alliance-focused foreign policy.”

A successful summit between Biden and Moon, several experts said, would lead to a stronger relationship among the U.S., South Korea and Japan, and perhaps ease the historical strains between the two Asian states. Biden’s first White House meeting with a foreign leader was with Japan’s prime minister, Yoshihide Suga, a month ago.

“They’d love a three-way alliance ... that assures that South Korea as the linchpin and Japan as the cornerstone are rock solid,” Maxwell said.

Biden will also be looking to draw South Korea into engagement with “the Quad” — the informal alliance of the United States, Japan, Australia and India — which is widely viewed as a counterweight to China’s growing economic and military power.

Seoul has sought to avoid making a strategic choice between aligning fully with the U.S., its most critical military ally, and maintaining relations with China, its largest trading partner. But it could engage with the four-nation alliance on specific efforts — those that China wouldn’t consider threatening.

That could include development projects, infrastructure financing and women’s empowerment programs, said Michael Green, an authority on Asia and Japan at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. If Moon is reluctant to coordinate on such things with the Quad, Green continued, that would send a discouraging signal about the sway on Seoul of Beijing’s pressure campaign.

“A lot of us worry,” Green said, “that Beijing may interpret the hesitancy to even do those kinds of things as a temptation for China to think that pressure will work.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.