Explainer: The differences between the two voting rights bills

- Share via

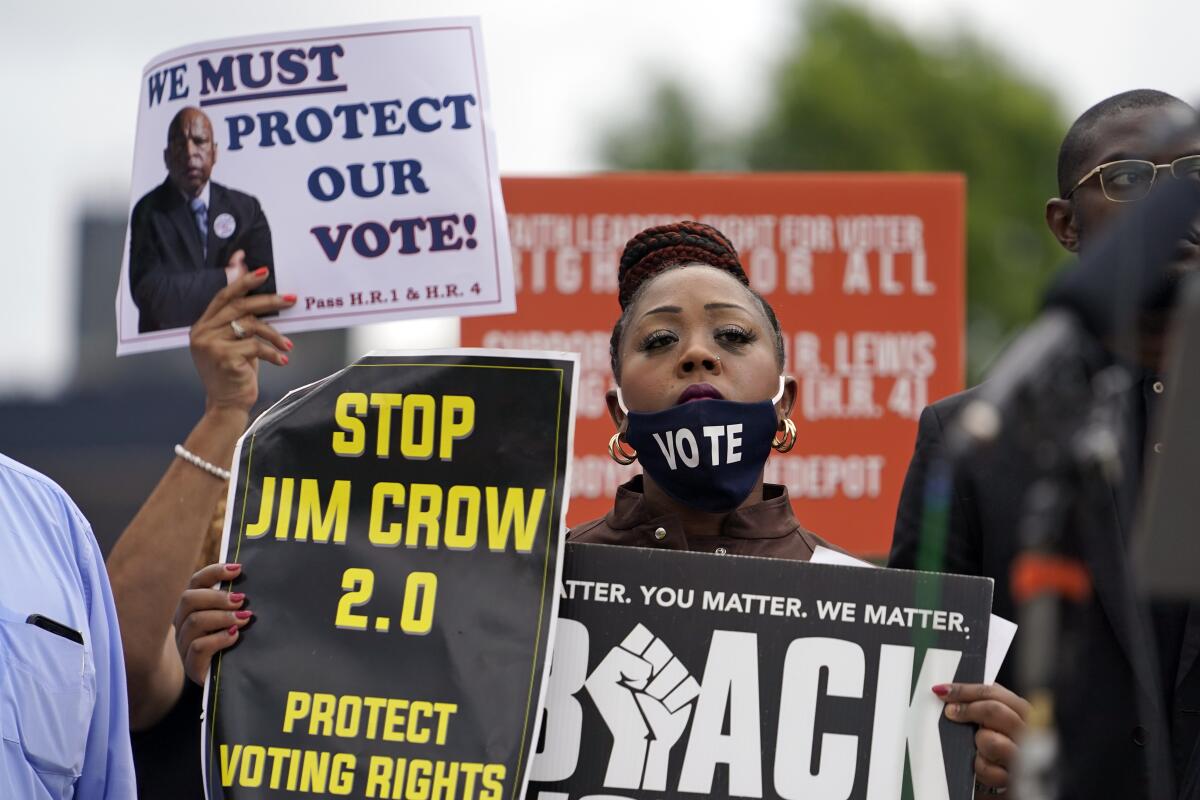

DENVER — The Democratic Party’s hopes of passing a massive overhaul of elections may have suffered a fatal blow when West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin III became the first member of the party to say he wouldn’t support it, ensuring the bill, known as HR 1, would not pass the Senate.

Manchin, however, does favor an update to the Voting Rights Act known as HR 4, or the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, named after the late congressman and civil rights leader.

HR 1 is an ambitious proposal that would transform many aspects of elections and campaigns across the country, including how they’re financed. Written in 2017, when Democrats were out of power, it was then referred to as a messaging bill — a proposal for candidates to tout on the campaign trail and not crafted specifically to garner enough votes to pass into law at that time.

In contrast, the John Lewis Act is a comparatively narrow bill designed to fix a specific problem, in this case, addressing a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that made it harder for the federal government to block racially discriminatory voting laws and redistricting proposals.

Democrats will struggle to get either bill through Congress, as they look for a way to combat the Republican-led efforts to restrict voting in state legislatures around the country. Here’s a look at the differences between the bills:

A key Democratic senator says he won’t vote for the largest overhaul of U.S. election law in at least a generation.

What’s in the Bills?

HR 1’s number shows its importance to Democrats. Also known as the For the People Act, it became HR 1 because it was the first bill on the House floor after Democrats retook the chamber in the 2018 election. (The Senate version is known as S 1.)

The bill does a little about a lot of topics. It changes the way people vote by automatically registering every eligible citizen, guaranteeing mail and early in-person voting options in every state and in effect neutering voter identification laws.

The legislation would also establish bipartisan commissions to draw the lines for legislative districts and require redistricting not favor either major party. The provision has the potential to create scores of newly competitive districts and, supporters say, would help counter the partisan polarization in the House.

The bill would provide $6 in public money to campaigns for every $1 in small-dollar donations they raise. Finally, it’d require groups currently shielded from disclosing their donors to identify their funders. The last provision targets a 2010 Supreme Court ruling, known as the Citizens United decision, that lets “dark money” groups hide their contributors even while getting involved in elections.

The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act was written in reaction to a different Supreme Court decision. It tries to essentially reverse the 2013 Shelby County case, in which the court’s conservative majority threw out the formula the federal government used to determine which states had such a history of racial discrimination in elections and were, under the Voting Right Act, required to have Justice Department approval before implementing new voting laws or redrawing legislative districts.

HR 4 would put in place an updated formula designed to meet the court’s Shelby County test. That would once again require about a dozen mostly Southern states to get approval from the Justice Department’s civil rights division before making those changes.

The bill would also make it easier for the department to send election observers and for courts to block election law changes for violating the constitutional protections guaranteeing voting rights for all U.S. citizens. And, of course, some of the elements from HR 1 could always be added in if the John Lewis Act becomes Democrats’ primary vehicle for an election overhaul.

Biden calls a Texas bill part of an ‘assault on democracy’

How Would the Bills Affect the New State GOP Laws to Restrict Voting?

The Democrats’ voting push isn’t happening in a vacuum. Republican-controlled states are passing new voting restrictions at a remarkable clip — the Brennan Center for Justice, a group that supports both HR 1 and HR 4, tallied up 14 states that have passed 22 laws putting new restrictions on when and how Americans vote. The GOP push has been fueled by former President Trump’s lies that he lost the election due to fraud.

HR 1 could neutralize some of these laws because it creates national standards for voting access. For example, new laws in Arizona and Florida that potentially remove from people from the states’ mail voting lists could be moot, because all voters would have a right to cast ballots by mail.

But the John Lewis Act would have no impact. The Justice Department would only be required to approve new laws, not ones that passed before the bill was approved. What’s more, the bill’s “preclearance” provision would only affect about a dozen states and some additional counties or cities that meet its standard. Manchin has talked about expanding preclearance nationwide, but that could run into problems with the Supreme Court.

Additionally, future laws could only be blocked under the bill’s new legal formula if they were deemed to be racially discriminatory by making it harder for specific racial groups to vote. Laws that present new hurdles for other groups — such as no longer accepting student IDs as voting identification, as Montana has done — could still be allowed.

Most importantly, neither bill would stop a trend of Republicans making it easier for partisan political officials to interfere in elections. In Georgia, for example, the GOP-controlled state Legislature now will appoint most members of a board that can replace local election officials. In Texas, Republicans are considering legislation that would make it easier for a judge to overturn an election.

A restrictive voting bill in Texas failed to pass Sunday after a dramatic Democratic walkout from the House chamber before a midnight deadline.

What Are the Chances of Either Bill Passing?

Not good. Democrats control the House and Senate, but narrowly. HR 1 has passed the House but is stuck in the Senate, where Manchin’s opposition means the bill doesn’t even get a majority and is nowhere near the 60 votes it needs to break a filibuster and pass. Currently, no Republican backs the bill.

The John Lewis Act hasn’t even been introduced in this Congress because of a lengthy fact-gathering and hearing process required to meet the Supreme Court’s new standard. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) in a letter to colleagues Tuesday predicted the bill won’t be introduced until the fall.

Prior updates to the Voting Rights Act passed the Senate unanimously — 98-0 as recently as 2006 — but earlier versions of HR 4 have only drawn one Republican sponsor, Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. That’s a testament to how partisan even the basic act of voting has become, a phenomenon that predates Trump.

Indeed, the Republican Senate leader, Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, on Tuesday criticized the John Lewis Act. “It’s against the law to discriminate in voting on the basis of race already, and so I think it’s unnecessary,” McConnell said.

Time is not on the side of Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D.-N.Y.), said Jessica Anderson, executive director of Heritage Action, a conservative group that opposes both bills. “Every day we inch closer to 2022, the harder it is for Schumer to get this to the finish line.”

What is Manchin’s Plan?

It’s unclear. He’s the former West Virginia secretary of state and warns that any voting reform that’s too partisan will simply increase distrust in elections. On the other hand, he says there needs to be some new election overhaul to protect voting rights.

One of those principles may have to give.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.