Historic double comet flyby coming Monday and Tuesday: Here’s what you need to know

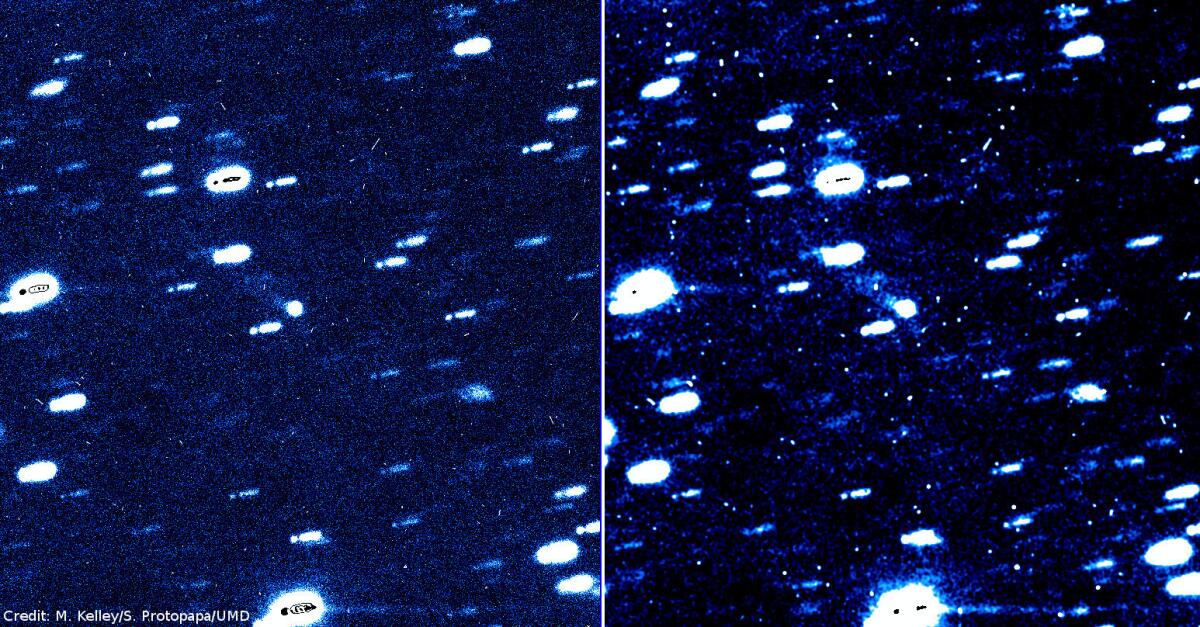

When does an asteroid become a comet? When it has a tail. These two images, taken by Michael Kelley and Silvia Protopapa confirmed “asteroid” P/2016 BA14 was actually a comet. The comet is at the center of the frame.

- Share via

Two comets are headed for a historic flyby of Earth this week, and you don’t want to miss them.

The bigger of the two bodies, known as 252P/LINEAR, is about 750 feet in size and surrounded by an emerald green cloud of gas. It is expected to make its closest approach to our planet on March 21 at 5:14 a.m. PDT.

At that time, it will come within 3.3 million miles of Earth, or about 14 times farther from our planet than the moon on March 21.

The next day, at 7:30 a.m. PDT, a second, smaller comet known as P/2016 BA14 will come even closer --flying within 2.2 million miles of our planet or 9.2 times farther from the Earth than the moon.

That will make it the closest comet to fly past Earth since 1770, according to Sky & Telescope, and the second closest comet to zip past Earth in recorded history.

“There are many more asteroids in near-Earth space than comets, which are significantly more rare,” said Michael Kelley, an astronomer at the University of Maryland. “When a comet does come this close to Earth it is something to get excited about, and take advantage of to learn whatever we can.”

It is possible that comet 252P/LINEAR will be visible to the naked eye eventually. It is expected to grow brighter as it flies toward the sun and more gases sublimate out of its nucleus. However, it will be too far south in the sky to be visible in the northern hemisphere at the time of closest approach.

P/2016 BA14 appears to be quite small and may never grow bright enough to be easily spotted without a telescope, experts said.

If you want to see live video of the comets as they zip past Earth online, the astronomy website The Virtual Telescope is planning two live broadcasts on March 21 and 22.

The bigger comet, 252P/LINEAR, was discovered in April 2000, but the smaller comet was only spotted two months ago in late January. Astronomers using the Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawaii originally had it pegged as an asteroid rather than a comet because they could not yet see a tail.

Russian astronomer Denis Denisenko of Moscow State University noticed that little P/2016 BA14 had a remarkably similar orbit to 252P/LINEAR and wondered whether the two bodies might be related. He shared this observation on the Yahoo Comets mailing list where international professional and amateur comet-watchers trade information.

Kelley and his colleague at the University of Maryland, Matthew Knight, saw Denisenko’s post and were intrigued.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

March 20, 11:18 p.m.: A previous version of this story incorrectly identified University of Maryland astronomer Matthew Knight as Michael Knight.

------------

“What are the chances of such an unusual comet and a random asteroid having a similar orbit and Earth close approach?” Kelley wrote on his blog in February. “Probably very small! A lot of suspicion was starting to be cast on this so-called asteroid.”

That same month, Kelley and Knight were able to take images of P/2015 BA14 using a 4.3-meter telescope in Arizona. Both observations showed that the small “asteroid” did indeed have a tail. It was a comet after all.

“It was a really exciting moment,” Kelley told The Times. “I study comets all the time, but I never get the chance to discover them. This was the closest I’ve come.”

Now the astronomy community is trying to determine the relationship between the two bodies. It is extremely improbable that two totally independent comets would fly so close to Earth at almost the same time, Kelley said. Although their orbits are not identical, they are close enough to suggest that they may be two pieces of the same comet that broke apart in the recent past.

To find out, astronomers around the world plan to closely observe the two comets with a variety of instruments, including the Hubble Space Telescope and the Goldstone Deep Space network, to see how similar their orbits are and whether their gas clouds have the same spectral fingerprint.

Kelley said a comet might fracture in two for a a number of reasons. It is possible that the larger body began to rotate too fast and needed to shed mass to stay together. It might be that energy from the sun causes the ices in the nucleus to warm up so rapidly in a particular area that pressure builds up and causes an explosion. Or, it could be that the comet got too close to a planet and the planet’s gravity caused it tear apart.

The researchers hope to learn more after the two comets, or possibly two pieces of a single comet, speed by this week.

No matter what they learn, it should be interesting.

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.