Q&A: Neuroscientist Eric R. Kandel on the biology of mind

- Share via

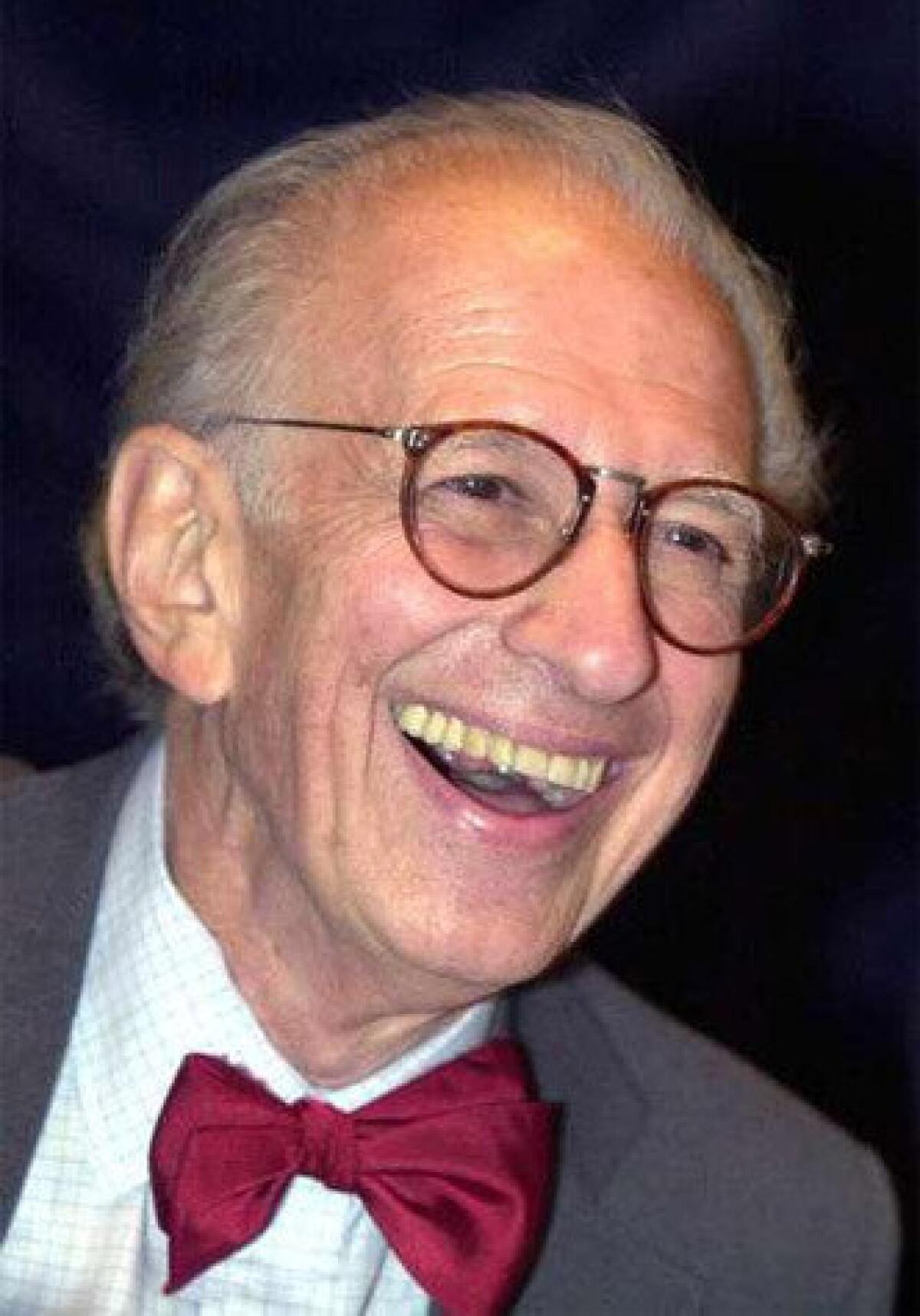

Neuroscientist and Nobel laureate Eric R. Kandel is haunted by his childhood memory of Nazis expelling his family from Vienna.

Or, in biological terms, a sensory experience of group violence during a time of developmental neuroplasticity strengthened synaptic connections and altered the morphology and function of his neural axons.

For one of the foundational theorists of the biology of mind, either interpretation holds. The introspective and empirical approaches have always been two sides of the same coin for Kandel, who fused intellectual history and memoir in his award-winning 2006 book, “In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind.” This year, Kandel extended the technique in “The Age of Insight,” a neuroaesthetic analysis of the early 20th century expressionist art of the city that spurned him.

At 84, Kandel has become more expansive and reflective. But he is no less rooted to a neuron-by-neuron approach that helped him chart the biological genesis of memory in the lowly sea snail, a feat for which he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2000. He shared that honor with Arvid Karlsson and Paul Greengard, pioneers in the effort to decipher the signal pathways regulating the brain’s most complex functions.

Kandel, a professor at Columbia University and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, was in Southern California for the recent Society for Neuroscience conference in San Diego and the Leo Rangell Lecture at UCLA’s Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, where he is a visiting scholar. He sat down to talk about his books, his work and the state of neuroscience.

Q: You have not changed your philosophy of keeping with simple models?

A: No. I think simple models are very helpful. I work in parallel on the mouse. I just think deep understanding is better than superficial understanding. Many people think that the task of the neurologist is to understand what is considered the connectome -- that is, how neurons connect to one another. But that is a limited insight into what the problems are. One has to know what are the functional connections, not just the anatomical connections and how do they participate in controlling behavior.

Q: Is there anything being lost in the effort to map the brain, as proposed by the Obama administration?

A: There was a worry in the beginning, when terms like this were being thrown around loosely … but early on, Francis Collins and the leadership of [the National Institutes of Health] had the sense to call around, and they put together an extraordinary science advisory board … and to a person this is first-rate. They’re really studying the problem. … I think it could have a major impact.

The problem is there’s no money. The amounts of money that Obama’s thinking about just don’t come close to approaching what needs to be done. And the worry is that some of those funds that will be used will be taken away from ongoing research efforts. Never in my life has the ongoing research effort suffered as much as it is suffering now. It’s a terrible time out there. What needs to be done besides the Obama funding, is just general funding for science.

Q: Is the problem from the sequester, or politics in general in Washington?

A: Since the [NIH Director Harold E.] Varmus era (1993-1999), there has been an enormous decline in the funds available. … People can’t get jobs. If they can get a job, they can’t get funding. It’s a very, very difficult situation out there. When I came along, if you could read and write in science, you were supported -- if you were at all decent. Now it’s very hard. Good people are not getting supported. … It’s a tragedy to have such good people not have optimal jobs that they want.

Q: Are there enough people looking at the detailed biochemistry, as opposed to networks, of the brain?

A: There’s a lot of work going on in synaptic plasticity. … There are a number of people making contributions to that. I think if you just look at the study of learning, which is really an outgrowth of synaptic function, that has made marvelous progress in the last 20 years. We’re just at the beginning – it’s an immense problem, but there’s been very good progress there.

Q: You’ve written a book recently, returning to the topic of Vienna. So let’s talk about memory and memoir. As you get older, how do you come to grips with your own memory?

A: I’m obviously coming to grips with my earlier life, which is not easy. And I’ve tried to handle that in part by becoming more engaged with Vienna. I received an honorary degree from the University of Vienna Medical School in 1985 or 1986, or something like that. And I was asked to speak on behalf of the other recipients. So I thought I would blast them for what they did in 1938 and 1939 and afterward. And then after thinking about it a week or two, I decided this was not the occasion for that: “They’re honoring you, so be decent. You’ll have other occasions to be critical.” And so I began to read up on the history of the Vienna School of Medicine. It’s a really extraordinary history, how much it accomplished and how it pioneered modern medical science. And that kept me engaged with Viennese intellectual life.

When I won the Nobel Prize -- the telephone rings off the hook for everybody -- a lot of these calls came from Vienna saying: Isn’t it wonderful to have another Austrian Nobel Prize? I said, this an American Nobel Prize – an American Jewish Nobel Prize. I thought I’d stick it to them. So the president of Austria wrote to me and asked, how can we honor you. I said I didn’t need any more honors, but it would be nice to have a symposium on how Austria responded to National Socialism. And they gave me the freedom to do that. I got some wonderful historians to help me organize a symposium at the University of Vienna, and that got me involved with current intellectual life in Austria, and with the leadership. I now know the new president, Heinz Fischer. We’re really good friends. I know the Chancellor of Austria. These are decent human beings, with zero tolerance of anti-Semitism.

There is still anti-Semitism in Austria, but it doesn’t come from the leadership of the [Social Democratic] party. It comes from conservative elements that have always been in Austria, and that, in Hungary, now are a dominant force. There’s a lot of anti-Semitism in different parts of Europe. So, I’m more involved in Austria than before. I’ve used that to think about it and write this book on art. It’s a follow-up to my earlier book, which is sort of a memoir.

Q: It’s a persistent memory for you, then?

A: It’s the driving memory of my life. It’s not easy getting kicked out your country when you’re 9 years old, leave your parents.

Q: Did that inform your passage into studying memory?

A: It did. That, and the fantastic experience I’ve had here. I’ve had just an absolutely privileged life in the United States.

Q: Do you think in this century we’ll arrive at a point where we can identify biomarkers for virtually anything having to do with mind?

A: I’m not sure, but I hope so. We had a Charlie Rose program on the Obama initiative, and Charlie turned to me and said, how long will it take to understand the human mind? And I said, a hundred years. And we’ll make progress all along, but it’s an enormous problem. I hope I’m wrong. I hope it’s 95!