Victims of Havana embassy ‘sonic attack’ have distinctly different brains, MRIs show

- Share via

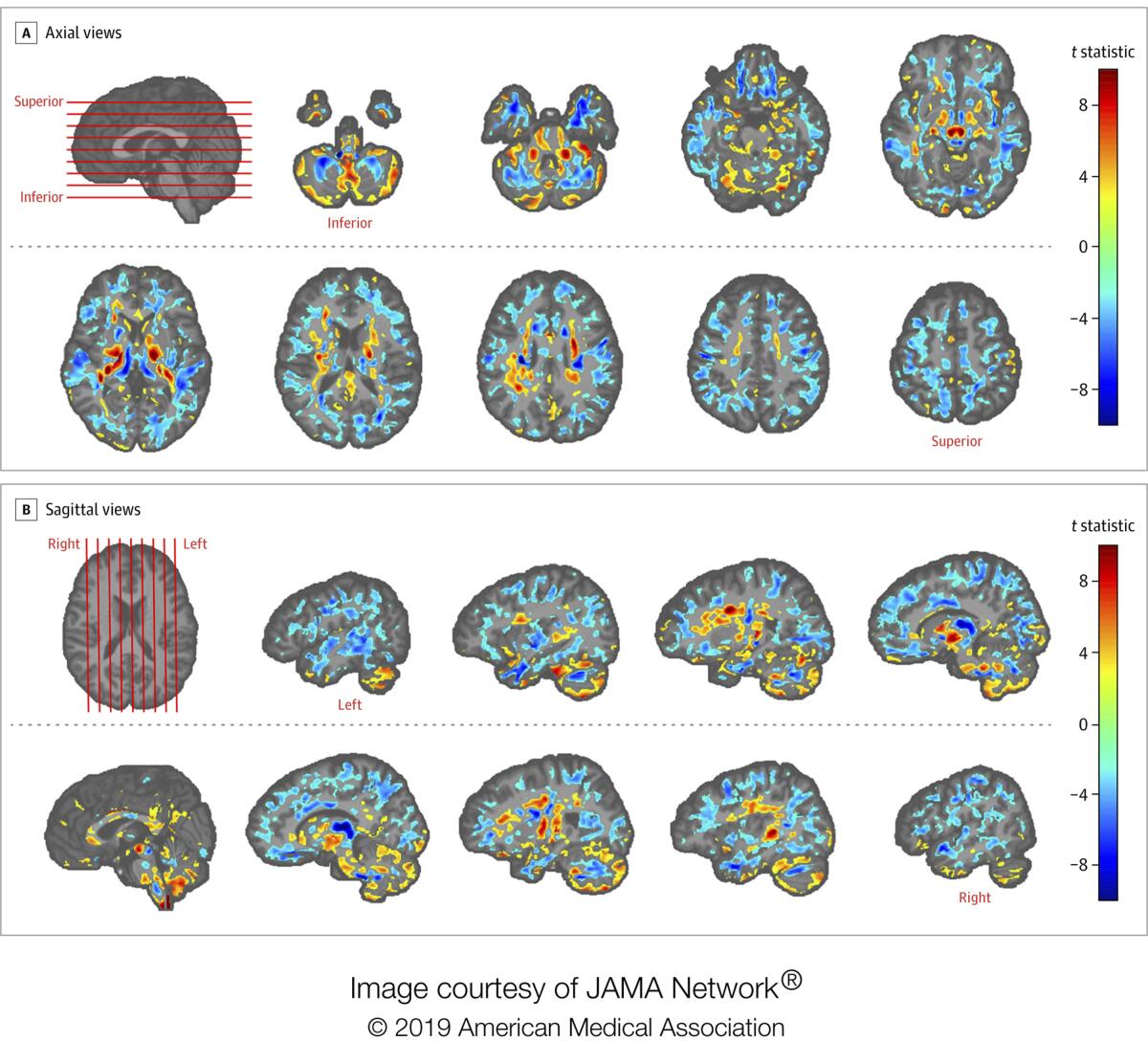

Advanced brain scans found perplexing differences in U.S. diplomats who say they developed concussion-like symptoms after working in Cuba — a finding that only heightens the mystery of what may have happened to them, a new study says.

Extensive imaging tests showed the workers had less white matter than a comparison group of healthy people, researchers reported Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. Other structural differences were found as well.

Given the workers’ reported symptoms — balance problems, sleep and thinking difficulties, headaches and other complaints — the researchers had expected the cerebellum, near the brain stem, to be affected. But they also found unique patterns in tissue connecting brain regions.

Study leader Ragini Verma, a University of Pennsylvania brain imaging specialist, said the patterns were unlike anything she’s seen from brain diseases or injuries.

“It is pretty strange,” Verma said. “It’s a true medical mystery.”

Co-author Dr. Randel Swanson, a Penn specialist in brain injury rehabilitation, said “there’s no question that something happened,” but imaging tests can’t determine what it was.

University of Edinburgh neurologist Jon Stone, who wasn’t involved in the study, said the advanced MRI scans don’t confirm that any brain injury occurred, nor that the brain differences resulted from the strange experiences the diplomats said happened in Havana.

Cuba has denied any kind of attack, which has strained relations with the United States.

An editor’s note published along with the study says it may improve understanding of the reported symptoms. However, it emphasized that the relevance of the brain differences is uncertain.

The U.S. State Department said in a statement that it “is aware of the study and welcomes the medical community’s discussion on this incredibly complex issue. The Department’s top priority remains the safety, security, and well-being of its staff.”

Between late 2016 and May 2018, several U.S. and Canadian diplomats in Havana complained of health problems from an unknown cause. One U.S. government count put the number of American personnel affected at 26.

Some reported hearing high-pitched sounds, similar to crickets, while at home or staying in hotels, leading to an early theory of a sonic attack. An interim FBI report found no evidence that sound waves could have caused the damage.

Dozens of U.S. diplomats, family members and other workers sought exams. The new study reports on 40 of them tested at the University of Pennsylvania.

A group analysis of results from the advanced MRI scans found brain differences in the diplomat group compared with 48 healthy people with similar ages and ethnic backgrounds.

Workers had MRI tests about six months after reporting problems, but because their brains were not scanned before they went to Cuba, researchers can’t tell if anything changed in their brains. The study authors acknowledged that limitation in their work.

Stone said the new study has several other weaknesses, including a comparison group that wasn’t evenly matched to the patients.

“If you really want to suggest that something fundamentally different happened in Cuba ... then the best control group would be 40 individuals with the same symptoms who hadn’t been to Cuba and had no history of head injury,” Stone said.

The latest study builds on earlier preliminary reports involving 21 U.S. workers who got brain scans showing less detailed white matter changes. The new study includes 20 of those workers.

A previous study from the University of Miami found inner-ear damage in some workers who complained of strange noises and sensations, but it also lacked any pre-symptom medical records.

Although some workers have persistent symptoms, most have improved with physical and occupational therapy, are doing well and have returned to work, Swanson said.

As more time passes, he said, “it’s going to be harder and harder to figure out what really happened.”

Tanner writes for the Associated Press.