3 scientists who learned how cells react to oxygen levels win Nobel Prize in medicine

- Share via

LONDON — Two Americans and a British scientist won the 2019 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for discovering how the body’s cells sense and react to oxygen levels, work that has paved the way for new strategies to fight anemia, cancer and other diseases, the Nobel Committee announced Monday.

Drs. William G. Kaelin Jr. of Harvard University, Gregg L. Semenza of Johns Hopkins University and Peter J. Ratcliffe of the Francis Crick Institute in Britain and Oxford University will share equally the $918,000 cash award, according to the Karolinska Institute, where the Nobel Committee is based.

Their work has “greatly expanded our knowledge of how physiological response makes life possible,” the committee said, explaining that the scientists identified the biological machinery that regulates how genes respond to varying levels of oxygen. That response is key to things like producing red blood cells, generating new blood vessels and fine-tuning the immune system.

Scientists are focused on developing drugs that can treat diseases either by activating or blocking the body’s oxygen-sensing machinery, the Nobel Committee said.

The oxygen response is hijacked by cancer cells, for example, which stimulate formation of blood vessels to help themselves grow. And people with kidney failure often get hormonal treatments for anemia, but the work of the laureates points the way toward new treatments, said committee member Nils-Goran Larsson, a researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Experts in the field praised the Nobel Committee’s choice.

“Thanks to this research, we know much more about how different levels of oxygen impact on physiological processes in our bodies,” said Bridget Lumb, president of the Physiological Society in London. “This has huge implications for everything from recovery from injury and protection from disease, through to improving exercise performance.”

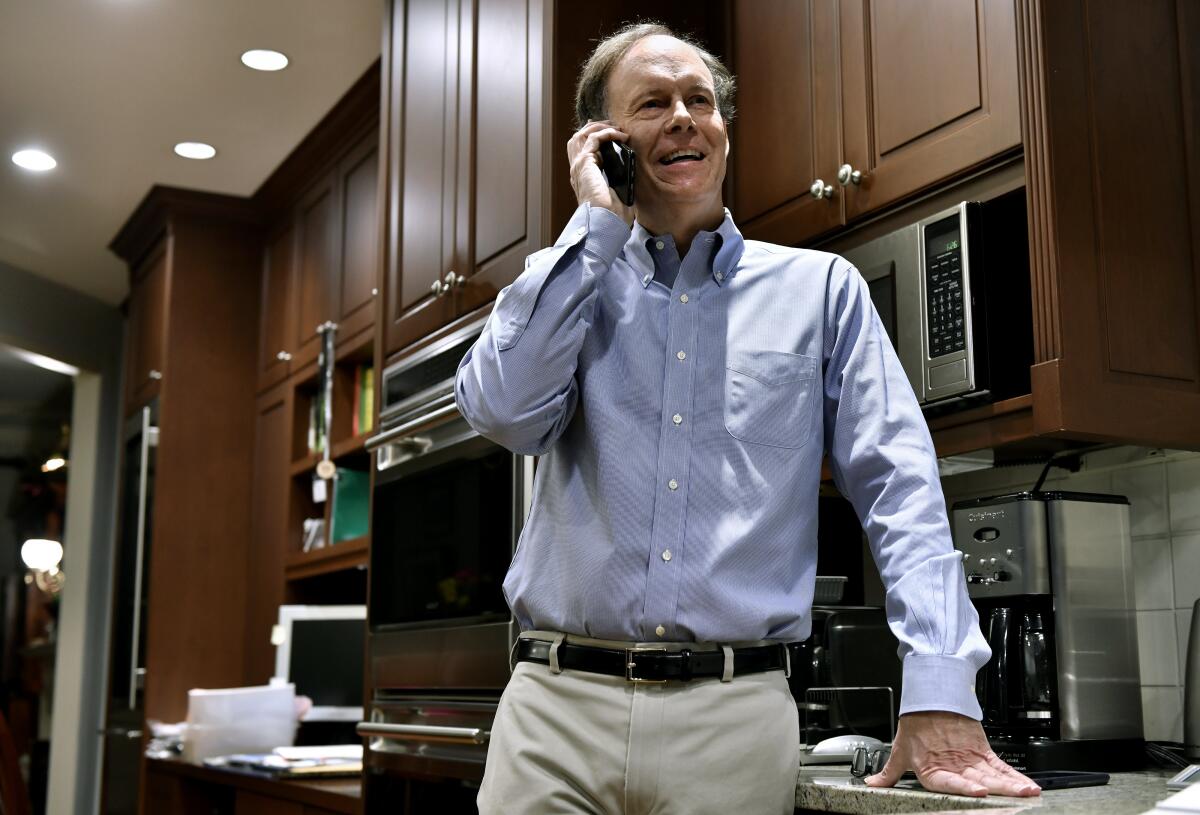

Kaelin said he was half-asleep Monday morning when the phone rang. It was Stockholm.

“I was aware as a scientist that if you get a phone call at 5 a.m. with too many digits, it’s sometimes very good news, and my heart started racing,” the 61-year-old said. “It was all a bit surreal.”

Kaelin said he wasn’t sure yet how he’d spend the prize money, but “obviously I’ll try to put it to some good cause.”

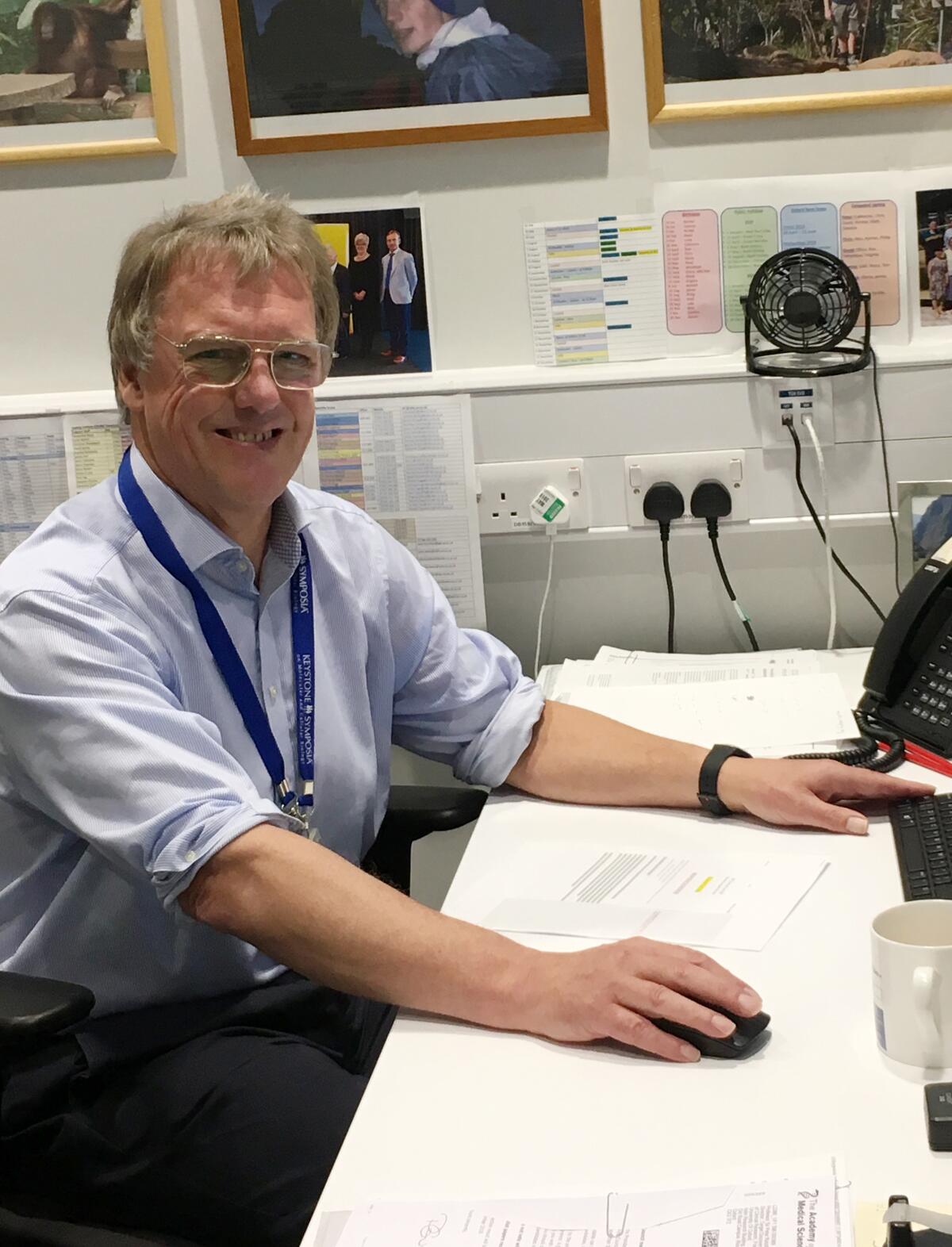

Ratcliffe, 65, said he was summoned out of a meeting Monday morning by his secretary, who had “a look of urgency.” The man on the phone “had a Swedish accent, so I figured it probably wasn’t one of my friends pulling my leg,” he said.

Trained as a kidney doctor, Ratcliffe said his research began in 1990 when he and colleagues simply wanted to figure out how cells sensed oxygen.

“I thought it was a definable problem and just thought we’d find out how it worked,” he said. They were about two years into the research program when they realized the discovery had much wider significance.

“We saw that it wasn’t just cells in the kidney that know how to sense oxygen, but all cells in the body,” he said. “They use this to do a huge range of other things, reprogram the cells, cause the growth of blood vessels, differentiation of cells. There are hundreds and thousands of processes the body uses to adapt to and regulate its oxygen levels.”

He said although some promising drugs had been developed, including for kidney patients who don’t get enough oxygen, it will be years before it’s clear how many lives will be changed by such discoveries.

Ratcliffe described his fellow laureates as “colleagues, competitors and friends.” He said he felt honored by the Nobel accolade but that his main goal had always been pure science.

“The satisfaction is really finding things out that will continue to be true for all time,” he said. “This is for me an eternal truth, and as a scientist, we work away, we find these things out, and we hope they will be useful.”

Semenza, 63, said he and colleagues were studying a gene in a rare cell type in the kidney and did an experiment that showed the factor they discovered was linked to oxygen. That’s when they realized it could have widespread physiological importance.

It turns out that the gene turns on erythropoietin, or EPO, when cells don’t get enough oxygen. EPO controls the production of red blood cells.

“We found it very interesting that the body can respond to oxygen,” Semenza said. That discovery has led to treatments for people with chronic kidney disease who become anemic when their kidneys stop making EPO. “Now, drugs can turn on EPO production by increasing these factors.”

It’s likely one or more of these drugs will be approved for production in the next few years, and one has already been green-lighted in China, he said.

Andrew Murray, a physiologist at the University of Cambridge, said the three laureates’ discovery was fundamental to understanding how to combat diseases of the heart and lungs as well as numerous cancers.

“Low oxygen levels are a feature of some of the most life-threatening diseases,” he said. “When cells are short of oxygen, as is the case with heart failure and lung disease, the tissues need to respond to that in order to maintain energy levels.”

Murray said the case of cancer was slightly different. Some cancer tumors thrive under low oxygen conditions, so scientists are trying to develop drugs to manipulate oxygen levels under these circumstances. “The work they have done is already leading the way to drugs that manipulate oxygen-sensing pathways,” he said.

Monday’s announcement kicked off this year’s Nobel Prizes. The prize in physics will be handed out Tuesday, followed by the chemistry prize on Wednesday. This year’s doubleheader literature prizes — one each for 2018 and 2019 — will be awarded Thursday, and the peace prize will be announced Friday.

The 2018 Nobel Prize in literature was suspended after a sex abuse scandal rocked the Swedish Academy, the body that awards the literature prizes, so two prizes will be given out this year.

The economics prize will be awarded Oct. 14. Officially known as the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, it wasn’t created by Nobel but by Riksbanken, Sweden’s central bank, in 1968.

The laureates will receive their awards at white-tie ceremonies in Stockholm and Oslo on Dec. 10 — the anniversary of Nobel’s death in 1896.