‘The wound never heals’: 25 years after their daughter was killed, Denise Huber’s parents say time helps — but only to an extent

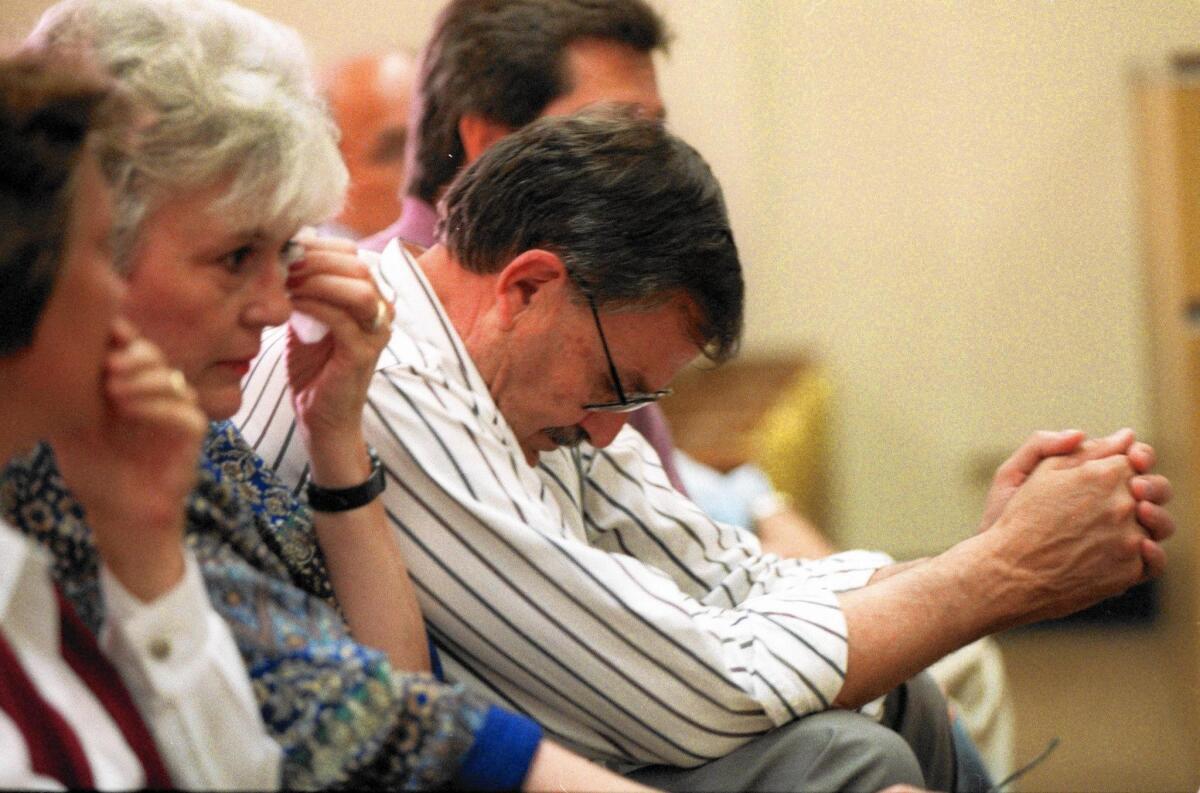

Dennis and Ione Huber hugged in Orange County Superior Court in 1997 after the death penalty was handed down to John J. Famalaro, the convicted killer of their daughter, Denise Huber.

- Share via

Shortly after 2 a.m. on June 3, 1991, 23-year-old Denise Huber was driving home from a Morrissey concert in Inglewood when her car blew a tire on the 73 toll road.

She was just minutes from the Newport Beach house she shared with her parents.

Even while wearing the heels she’d donned for the concert, it should have been a relatively quick walk to a call box or even a nearby gas station where she could have asked for help.

But her parents, Dennis and Ione Huber, never heard from Denise that night. In the morning, they began calling her friends, asking where she could be.

That night, around 10 p.m., one of those friends found Denise’s Honda still on the side of the freeway, unlocked, its battery drained from the emergency blinkers that had been left running. Denise was gone.

It would take three years — and what the Huber family to this day considers a miracle — before police would discover Denise’s body.

During that time, her family placed a 6-by-30-foot banner on the roof of an apartment building overlooking the area where her abandoned car was discovered. It read “Have You Seen?” and included Huber’s likeness, a physical description and the phone number for the Costa Mesa Police Department.

The parents went on television to share their story as they worried and waited for any shred of information.

Dennis especially threw himself into the pursuit.

“My car was like a rolling billboard with signs all over it,” he said. “I looked. Every time I saw some girl with long brown hair, I’d want to see her face.”

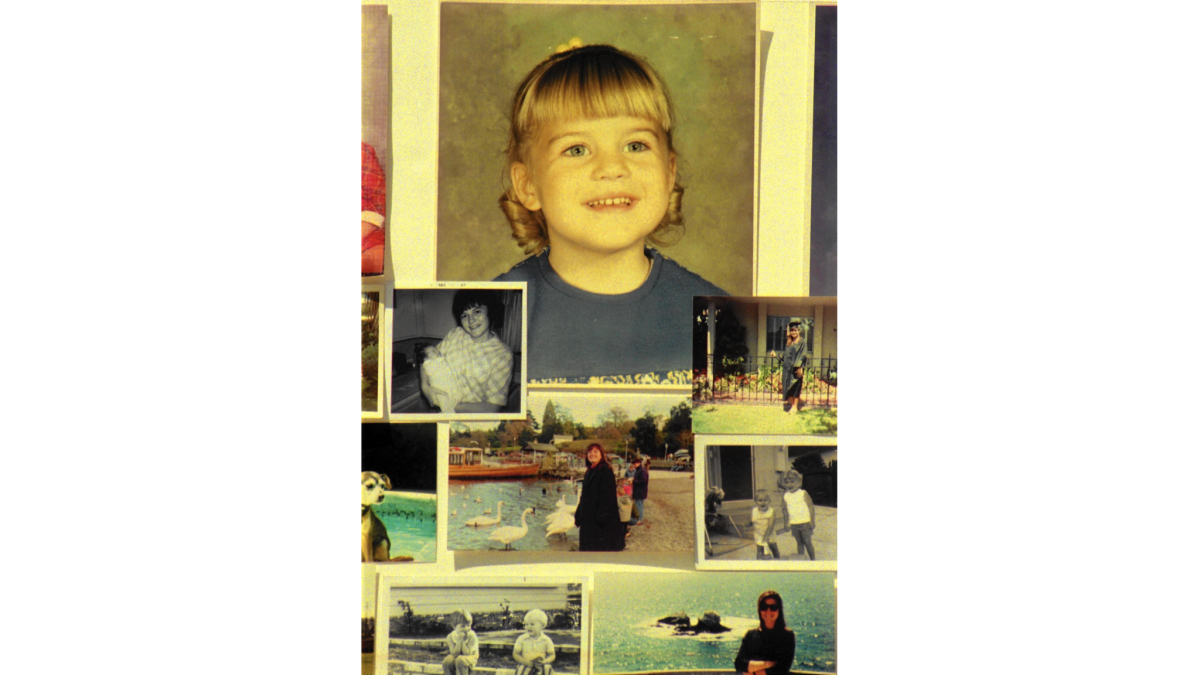

A poster board with dozens of pictures of the slain Denise Huber. It was displayed at a memorial service held in Huber’s memory in 1994 at the Mariner’s Church in Newport Beach.

Authorities eventually came to believe that John Famalaro, a 34-year-old painter, had pulled up as Denise walked along the side of the freeway.

Famalaro sexually assaulted her and killed her by slamming a nail remover into Denise’s skull more than 30 times in a Laguna Hills warehouse where he lived and ran his painting business.

Instead of disposing of the body, Famalaro kept it in a large freezer, even taking it with him when he moved to Arizona.

Famalaro was sentenced to death for the murder in 1997.

Now 59, Famalaro is awaiting the fulfillment of his sentence in San Quentin State Prison, but like other death row inmates in California, it’s an open question whether the day of his execution will ever arrive.

Although the California Supreme Court upheld Famalaro’s sentence in 2011, another appeal is pending, and it could take years to resolve.

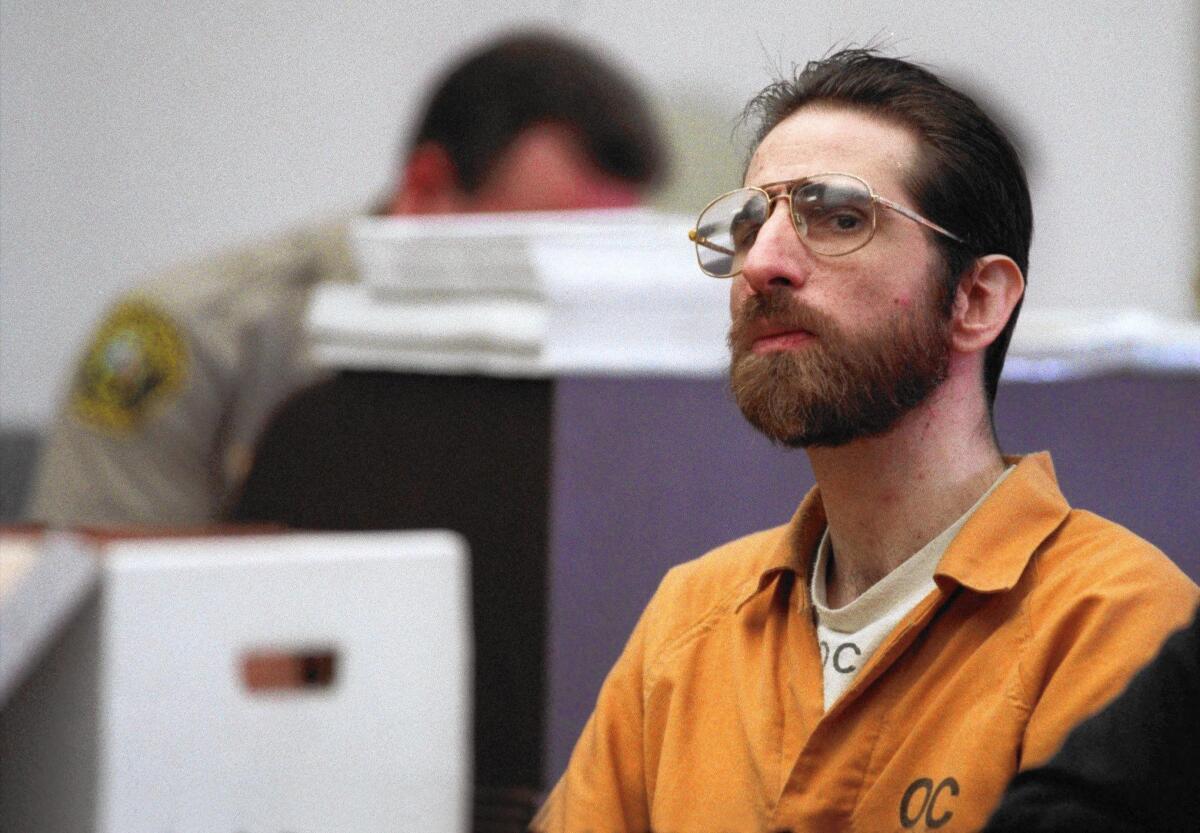

John Famalaro at the change of venue hearing on his murder trial for the death of Denise Huber.

But even if Famalaro’s appeals concluded tomorrow, his punishment would still have to wait because California has no approved method to execute inmates. Capital punishment has essentially been on hold since 2006 because of a judge’s ruling that the three-drug lethal injection used at the time could cause inhumane suffering.

“He’ll die of old age in the prison, I believe, before he gets the death penalty,” Dennis said.

“And we’ll probably die before he does,” Ione added.

The couple have been married 52 years. Dennis is now 77 and Ione is 73.

Last month marked the 25th anniversary of Denise’s death. Dennis and Ione say they’ve made peace with the fact that their daughter’s killer may never actually face the ultimate penalty prescribed for him.

“It’s done, I feel,” Dennis said. “There’s nothing more that can be done. It’s up to the state to do something with him.”

Speaking from their home on the bank of the Missouri River in South Dakota, the couple sound almost casual relaying details of the crime, except for the occasional twinge of pain revealed in their voices.

After all, they’ve spent 25 years talking about the tragedy, but the emotions can come back in an instant. Dennis said he still hurts deeply any time he sees a father-daughter relationship portrayed on TV.

“The wound never heals,” he explained. “You just learn how to deal with it, and it doesn’t hurt quite as much as it did at first.”

Time helps, Ione said, but only to an extent.

“I can’t tell you how much I still miss Denise,” she said. “I think of her every single day.”

I can’t tell you how much I still miss Denise ... I think of her every single day.

— Ione Huber

The couple agree that any pain they feel now pales in comparison to the arduous years in the early 1990s when they couldn’t answer the heart-wrenching question: Was their daughter still alive?

At the time, the Hubers’ desperate search struck a chord with the public. Denise’s disappearance became one of the most famous mysteries in Orange County, and it remains one of the area’s most infamous crimes.

From the outset, police had little to work with, according to Jack Archer, a now-retired Costa Mesa police detective who, with his partner, was assigned to lead the search for Denise.

Archer remembers the bare-bones crime scene on the side of the freeway — essentially an empty car. So the first step was to speak with Ione and Dennis, who’d reported Denise missing.

What they told Archer made him believe Denise hadn’t simply absconded. Almost immediately he suspected she was the victim of a serious crime.

“She was a young girl that wasn’t in trouble, wasn’t into drugs, didn’t appear to be rebellious,” Archer said. “She wasn’t someone that would just take off for days at a time.”

Archer and his partner then conducted interview after interview with friends, co-workers, acquaintances, anyone who might have an idea where Denise had gone, but they came up dry.

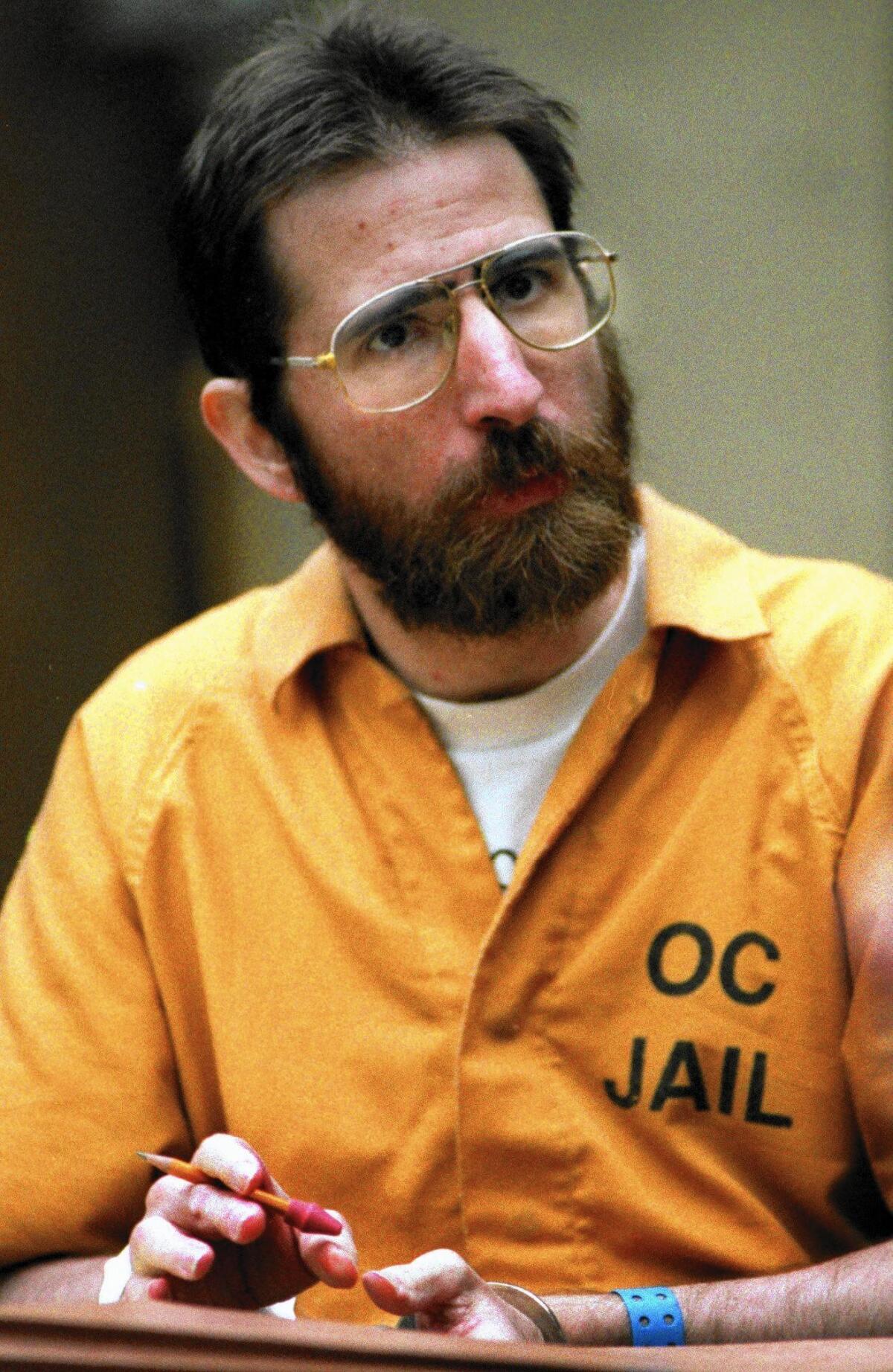

John Famalaro during the trial in 1997.

Grasping for any break in the case, police staked out the freeway where Denise disappeared, identifying drivers by taking pictures of license plates and then sending them letters asking if they’d seen anything suspicious the night of June 2.

But the trail was cold. Even psychics called in by police couldn’t point in a useful direction.

“All the leads that we had were exhausted,” Archer said.

About a year into the case, Archer took a new assignment at the department, rotating back to patrol, leaving Denise’s case behind.

The Hubers believe that July 13, 1994 — more than three years after Denise disappeared — is a day of divine intervention.

On that day, sheriff’s deputies in Yavapai County, Ariz., searched a 24-foot rental truck parked in the driveway of Famalaro’s home. A woman who bought paint from Famalaro had seen the truck and thought it suspicious enough to alert police.

“She saw the truck and she told us that she felt a spirit pulling her to that truck,” Dennis said. “She felt so compelled she wrote down the license plate number.”

When Yavapai County deputies ran the plate number, they discovered that the vehicle had been reported stolen in Orange County six months earlier.

Court documents say sheriff’s deputies thought they’d come upon a mobile drug lab when they discovered a power cord running to a padlocked freezer sealed with masking tape in the back of the truck.

But when a locksmith opened the freezer, deputies were met with a foul smell.

Inside, wrapped in layers of black trash bags, was Denise’s naked body.

Harry Tosado, manager of the Allsize Storage complex in San Clemente, stands in the doorway to a storage area in 1996 that Famalaro rented and kept a freezer from January 1992 to February 1994.

The next day, deputies served a search warrant on Famalaro’s home, where they found paperwork for a warehouse Famalaro had rented in Laguna Hills. Authorities believe he lived in and ran a painting business at the warehouse until he moved to Arizona in the summer of 1992.

In California, Archer was called back into the investigation to check on the Laguna Hills facility.

According to Archer, a witness there told police that the warehouse had to be cleaned after Famalaro moved out. One spot in particular was covered in what they thought was red paint.

The substance had been washed away by the time police entered the picture, but Archer decided to have a crew cut into the wall near where the stain had been.

“As soon as they flipped over the 2-by-4 on the bottom of the wall there was dried blood,” Archer said.

Police soon theorized that Famalaro took Denise to the warehouse after kidnapping her from the side of the freeway. There, he raped her and crushed in her skull with the nail puller, leaving behind a pool of blood.

The body, however, he couldn’t leave behind, Archer said.

In Famalaro’s Arizona house, investigators found boxes and boxes of trash, Archer said. The suspect had saved everything from hundreds of almost-empty paint cans to soda receipts from Jack-in-the-Box, the former detective said.

“He just could not throw anything away, and that’s what led to him getting caught.... He’s a hoarder,” Archer said. “If he would’ve gotten rid of the body in the middle of the desert on the way to Arizona, we might’ve never solved the case.”

Ione Huber, second from left, and Dennis Huber, the parents of Denise Huber, react to the guilty verdict given to defendant John Famalaro in Orange County Superior Court in 1997.

Dennis said he rarely thinks of Famalaro these days, but Ione said she does occasionally. She still has a question for the man convicted of killing her daughter:

Why?

Why did Famalaro choose Huber to be raped and bludgeoned to death? Why did he keep Denise’s body hidden, leaving her parents with false hope that she might still be alive?

The Hubers know Famalaro heard their pleas for answers. In his Arizona home, police found newspaper articles about his crime and a taped recording of one of their appearances on TV asking for help finding Denise.

“To be so cruel and so cold that he let us suffer like that,” Ione said, trailing off without finishing her sentence.

Even 25 years later, she doesn’t expect she’ll get an answer.

--

Jeremiah Dobruck, jeremiah.dobruck2@latimes.com

Twitter: @jeremiahdobruck

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.