His 1988 World Series ‘minute’ sustains Ex-Dodger Gilberto Reyes

After years in the minors, the Dodgers backup catcher arrived minutes too late to play in the series clincher. He has overcome setbacks, including time in jail.

- Share via

He was one step short of fame, one moment shy of memorable.

Gilberto Reyes is resting his graying head in his giant hands after spending eight hours carrying and cleaning folks at a nursing home. He is tired, but he has a story. It is a story about a brush with greatness so brief and unlikely it still doesn't seem real. In the 25th-anniversary season of the last and most improbable Dodgers championship, it is the most perfect of stories.

"Let me tell you about the minute I spent at the World Series," he says.

In 1988, Reyes was a longtime Dodgers minor league catcher who'd spent the last month of the regular season with the big league club. Then he sat on the Dodgers' bench as a nonroster player for the National League Championship Series and the first two games of the World Series.

When the rest of the team flew to Oakland to continue the series, he returned to his Dominican Republic home to begin play in the winter league. He was there watching Game 4 on television when he saw Dodgers catcher Mike Scioscia injure his knee on a slide into second base. After the game, his phone rang. It was the Dodgers. Scioscia was doubtful for Game 5, they needed a backup catcher, how fast could Reyes rejoin them?

"It was the call I had been waiting a lifetime to receive," Reyes remembers. "I was going to play in a World Series."

He jumped on a morning flight to Miami, changed planes and flew to Houston, changed planes again and flew to Oakland, landing at the airport as the final innings of Game 5 were being played down the street in the Oakland Coliseum.

A clubhouse worker picked him up at the airport curb, rushed him to the ballpark and escorted him down to the clubhouse, where Reyes found a sparkling new gray uniform hanging in his personalized locker. He hurriedly dressed, grabbed his bats and glove, tied his cleats, and hustled out a long tunnel to the field . . . where he promptly froze.

I was coming out to play, and they were all running inside to celebrate … I missed everything."— Gilberto Reyes.

He had arrived just as the Dodgers were dancing on the mound to celebrate clinching the 1988 World Series championship.

"I was coming out to play, and they were all running inside to celebrate," Reyes recalls. "I missed everything."

Well, not everything. After overcoming his initial shock, Reyes shrugged, picked up his gear, returned to the clubhouse, grabbed a bottle of champagne, and began spraying everything in sight.

"Tommy Lasorda was like, 'Gilberto, what are you doing, when did you get here?'" Reyes remembers. "I just keep shouting, 'We won, we won, yay!'"

The Dodgers flew back to Los Angeles a few hours later, arriving in the middle of the night. While the other players returned to the Bonaventure Hotel to sleep and prepare for the eventual parade, Reyes had breakfast in the lobby, caught a cab, and returned to the airport for a flight back to the Dominican Republic.

(Los Angeles Times)

He never played another game as a Dodger. He never again came so close to the glory he so barely missed. Five months later, in March 1989, he was traded to the Montreal Expos, setting him adrift on a journey that would go through 10 different minor and Mexican League teams, two stops in an alcohol rehabilitation center, and one excruciating 15-month stay in jail on drug distribution charges that were eventually dismissed.

Along the way he lost his World Series ring, his wife's World Series pendant and many of the baseball connections who once considered him a prime catching prospect.

That one step is now a million miles. That missed moment has become forever.

"So many things, gone," Reyes says.

There was a power outage at the nursing home on this Friday night, which meant plenty of scared residents. But Reyes, who moonlights as a nursing assistant, was ready. The Dodgers will tell you, he was always ready.

"I had to carry a lot of people out of their beds and into their wheelchairs, get them to the place with the emergency lights, there was all kinds of screaming," he says. "I once helped pitchers, now I help patients."

Even with the lights working, you probably wouldn't recognize or remember him. Perhaps no other member of that 1988 team was as anonymous then, and is as forgotten now. Yet perhaps nowhere is the power of that championship more evident than in the life of a man who has forged 25 years out of the minute he spent at the World Series.

"I'm glad somebody remembers," Reyes says. "Those memories have given me comfort and helped me survive."

He played in only five games that year, started only once, collected only one hit, but in the final month of the season was one of the Dodgers' secret weapons. During Orel Hershiser's record 59-consecutive-scoreless-innings streak, Reyes was one of his caddies. Reyes never caught an official Hershiser inning, but he would race down from the bullpen to warm up Hershiser before many of those innings.

Says Reyes: "I was Orel's good-luck charm."

Says Hershiser: "I remember Gilbert fondly. Because not every game was televised back then, there was less time between innings, and so you really appreciated the guy who runs off the bench, doesn't make you wait, and keeps you in rhythm."

I'm glad somebody remembers … Those memories have given me comfort and helped me survive.— Gilberto Reyes

Reyes celebrated with Hershiser in the clubhouse after he broke the record. He had previously celebrated the Dodgers' clinching the National League West. And, of course, he celebrated both the NLCS and World Series victories.

"People would say, 'You didn't even play, why are you celebrating like you hit a game-winning grand slam?'" Reyes recalls. "I would say, 'No, I'm celebrating like I just pitched a perfect game!'"

Then, just as quickly, the music stopped. His descent began when he was traded to Montreal that spring after complaining to Dodgers general manager Fred Claire that he could not bear to spend a fifth consecutive season in Albuquerque. He was always known as a partier, but when he joined the Expos organization, he mixed his insecurities with alcohol, drinking beer before games and whiskey afterward. He soon found himself asking the organization to send him to an alcohol rehabilitation center, which the Expos did, twice.

"This is a kid who had the best arm of any catcher in the Dodger organization, by far, and could have been a backup catcher in the big leagues for a long time," recalls Kevin Kennedy, then the Dodgers' minor league catching instructor. "But he was too carefree."

He played his only full big league season in 1991 with the Expos, and did well defensively by throwing out more than 50% of runners attempting to steal. But off the field he couldn't stay straight, and he was finally sent to dreary triple A and distant Mexican League baseball.

It was during this time that both of his parents died in the Dominican Republic. When he returned home to deal with their affairs, he learned the World Series ring he had given his father was gone.

"'That is when I thought I had lost it all," he says.

Yet rock bottom was still ahead. In the winter of 2007, he was retired and going broke, so he says he agreed to help a friend by moving some furniture between New Mexico and Colorado in a pickup truck for $2,000. When the truck skidded off a snowy highway in northeastern New Mexico, destroying the furniture, police found cellophane packages containing more than 400 pounds of marijuana.

Reyes was arrested and sent to the San Miguel County Detention Center in Las Vegas, N.M. He maintained his innocence while being given what he says were repeated offers that would have given him his release in exchange for pleading no contest to the drug trafficking charges.

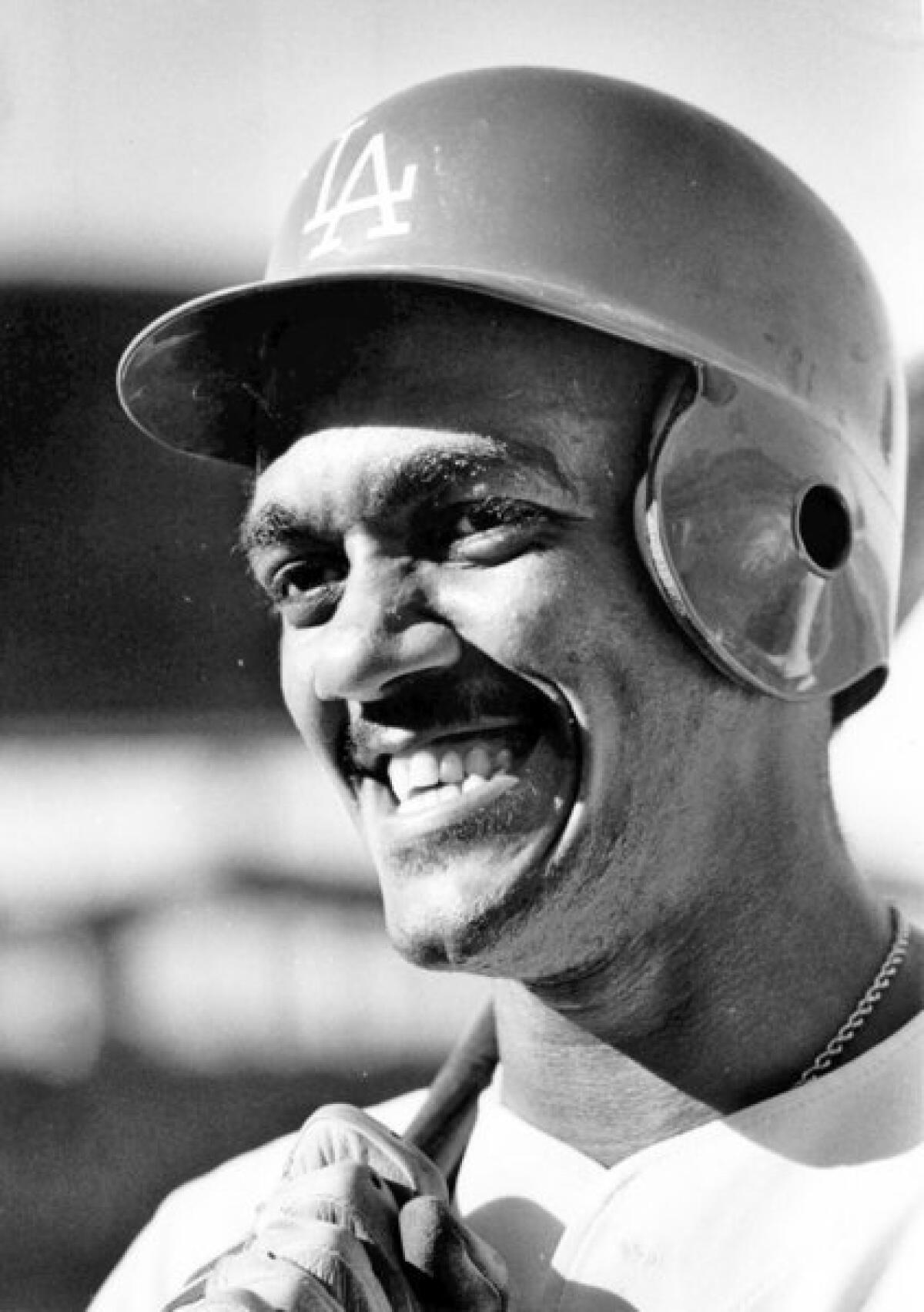

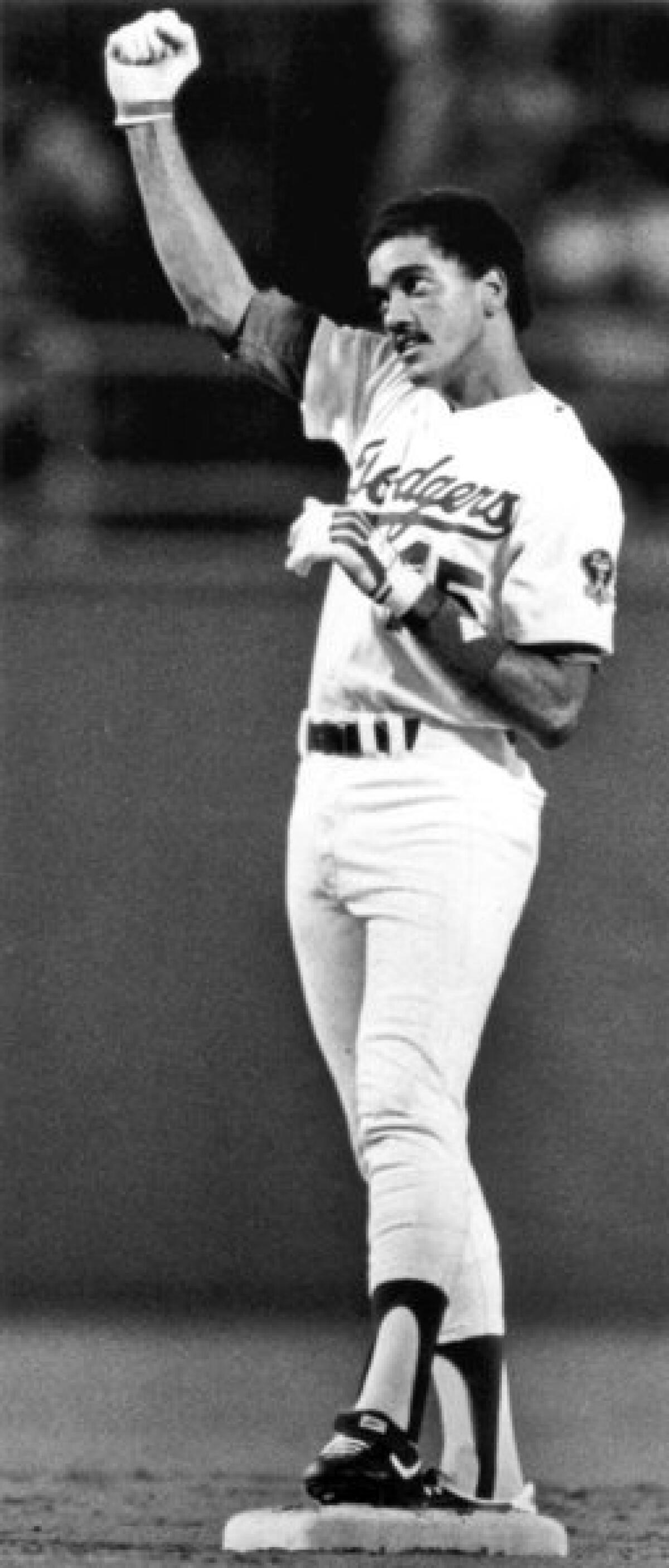

Gilberto Reyes, then a 19-year-old rookie, celebrates his first major league hit during his first home start at Dodger Stadium in 1983 (Los Angeles Times)

"I was stupid and naive to trust someone I didn't know, but I had no idea about any drugs, and I couldn't spend the rest of my life with people thinking I had done it," Reyes says. "I had to protect my good name."

He spent the next 15 months in jail protecting that name. He says he initially couldn't afford the $10,000 bond and, later, was fearful he would get deported when released, so he remained behind bars.

Because he wanted to keep a low profile to avoid trouble, none of his old baseball friends had any idea he was even in jail.

"I found out later, and I was absolutely shocked," says Claire, the man who made that World Series phone call to Reyes. "How could this have happened and nobody knew about it?"

Reyes' only visitor was a family friend who discovered his predicament after reading about it in a local newspaper.

"Every time I came, he looked so lost and felt so hopeless, nobody knew where he was or how to do anything for him." says Isabel Cavazos, a Las Vegas social worker who became his advocate. "But he was firm in his convictions."

He would hear fellow inmates being beaten or raped at night, and wondered if he would be next. Then, after a couple of months, he realized that the same memories that had sustained him could also save him.

"The people in the jail finally found out I was on the 1988 Dodgers, I was a world champion," he recalls. "But instead of making me a target, they asked me for stories. I gave them stories. They backed off. That championship season saved me."

His trial ended in a hung jury, and prosecutors dismissed the charges. Once he received his green card, Reyes brought his family from the Dominican and essentially started his life again.

So many things, gone, but so many things remain. Reyes, 49, has been sober for more than decade, he's a husband of 28 years, a father of three and a respected patient care technician at Albuquerque's Lovelace Medical Center.

"He's fabulous," says Jo Ellen Nutter, director of nursing for the intermediate care unit. "His ability to connect with people is amazing, and we have to think it's because of the leadership he learned in baseball."

Occasionally, those million miles feel like one step again. This happens when a patient whom he is bathing or lifting or simply comforting asks him what he did before he joined the hospital.

He has done many things, but he always answers with only one.

"I used to play for the Dodgers," Gilberto Reyes says proudly, to smiles and stares that bubble and spray.

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.