Little League’s boys and girls of summer are too young for TV

- Share via

I have just spent four squeamish hours watching children cry, children pout, children squirm, children crumble, children vainly attempt to hold themselves together in a situation that is not meant for children.

I have just seen a child miserably fail, then weep at that failure while his relatives scream in unvarnished disappointment.

I have just seen a child brilliantly succeed, but under such a spotlight that he also weeps, then attempts to pull his shirt over his face to hide the tears.

I have just seen an adult verbally insult the abilities of a child, and a child gesture and glare to insult an adult.

You know what I want to see now? I want to see whoever decided to put Little League baseball on television be placed in a permanent timeout.

I’ve written this column before, and I’ll write it again, and nobody will listen because more than 1 million people are usually watching, but the truth is as clear as those rivulets running down a strikeout victim’s cheeks.

Allowing the public viewing of pubescent angst under the guise of a baseball game is opportunistic, offensive and just plain wrong.

The 69 Little League World Series and qualifying games that are currently being shown on ESPN and ABC are the worst sort of reality television, turning 11-to-13-year-olds into adults, turning adults into kids, turning my stomach.

I don’t blame the networks, and this isn’t because I do some work for one of them. If ESPN and ABC don’t cash in on these midsummer ratings, somebody else will. It is incumbent upon the Little League bosses to stop this, or at least slow it, protecting their children by returning to the game’s humble televised beginnings, more than 50 years ago, when only the finals were shown and only on tape delay on ABC’s “Wide World of Sports.”

This month, it seems there are two or three games on TV every night — different teams, same sad scenes.

There is a scrawny pitcher who begins the game with eye black dripping all over his face. Then he gives up a few hits, and suddenly the polish is mixed with tears.

There is a stocky shortstop wearing sunglasses on his cap even though it’s a night game. Then he screams at an umpire’s call and drops a pop fly, and now the sunglasses are crooked, and he’s trying not to look at his grandparents growing pale in the stands.

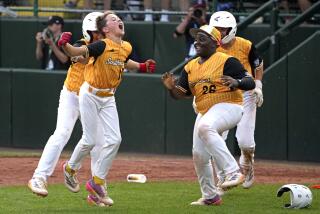

Then there is a coach in a tight shirt and shorts who huddles the team together between innings and barks into his TV microphone like Lombardi. He later grabs the kid who scores the winning run and twirls him around like a rag doll while the rest of the team hugs celebrates.

These are all common sights at any Little League field on any summer night around the country. This is all part of kids learning to grow up and adults learning to help them, and it’s not all bad.

We just don’t need to see it. And they don’t need us to see it. The cameras heighten the already incredible pressure and alter the already erratic behavior. The cameras needlessly deify and unfairly embarrass. The cameras change everything for kids who just aren’t ready for it.

Think about it — is there any other sport that agrees to televise a month’s worth of games played by kids? Even the notoriously young Olympics mostly require their participants to be at least 16. Even the most exploitative televised youth basketball events begin in high school.

And if you want to argue that people like to watch prodigies play baseball, well, this isn’t even the country’s best youth baseball. The lure of club and traveling teams has taken many great young players off the Little League fields, often turning these televised games into small-town or cultural battles that have little to do with baseball.

“These games are about a childhood innocence that just about everybody can relate to,” said Steve Barr, director of media relations for Little League International. “Most people played youth baseball, so watching these games evokes some good memories about when they played. Those memories aren’t always about baseball but about everything that surrounds it.”

He’s right about the innocence. Listening to the kids introduce themselves in their high-pitched voices, seeing one player wearing cleats signed by his favorite mascot, “The Chicken,” watching the little brothers and sisters dancing in the stands, it makes you want to find a snack table and buy a Blow Pop.

But then the game starts, and the players bite their lips, and the parents can’t hide their hurt, and one coach recently gathered his kids together late in the game to read his scouting report on the opposing pitcher. “This guy throws meatballs,” he told his team in words heard by more than 1 million people, particularly those who live in that young pitcher’s world, where he must now carry that insult forever.

Barr said that Little League uses much of the television rights fees to fund background checks for Little League volunteers around the world, certainly a worthy cause. But although a child’s safety is obviously priceless, is this kind of exposure the best way to pay for it?

“I know there are two sides to every issue, but we feel like it’s a positive, fun thing for the kids,” Barr said. “In sharing thoughts with ESPN, I just know we try to make it as positive as it can be.”

In recent years, the cameras indeed have lingered less on children who just dropped a fly ball, and this week, there were mercifully no shots of a team that was eliminated on a walk-off, inside-the-park home run. But there’s only so much the cameras can hide, and nothing is more obvious than the paradox that televised Little League baseball has become.

The kids are out of their league, and there’s nothing little about it.

twitter.com/billplaschke

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.