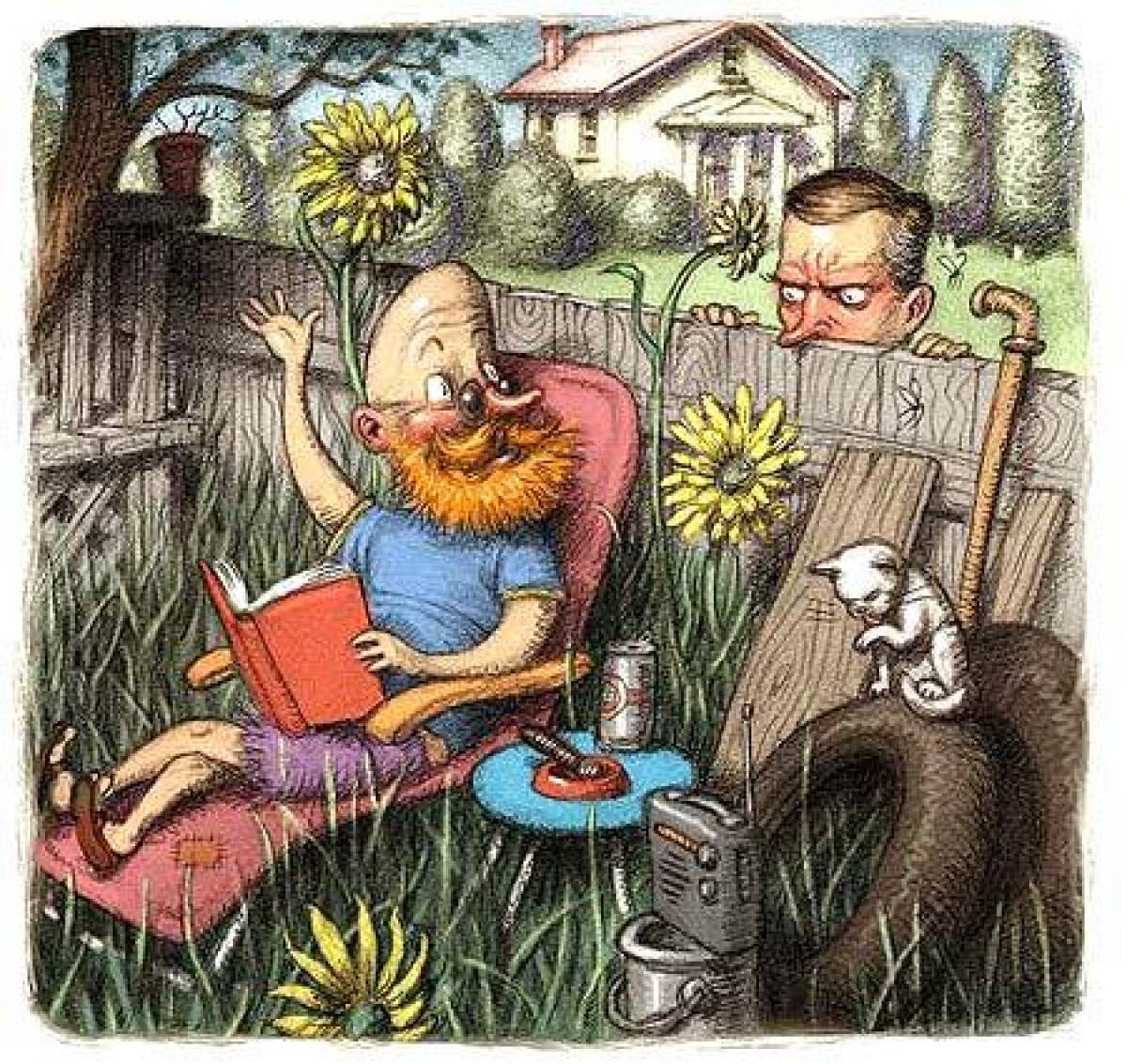

That’s right neighborly of you

- Share via

It was a basic tract house backyard — a little wider than the house itself and half as deep, with the usual wood-slat fence along the property line and the neighbor’s home just steps away. But Karen Kenney Walsh had sunk time and money into making her Irvine yard into a little slice of heaven. Putting green. Hot tub. Fishpond. New patio furniture. A calming landscape of gardenias and azaleas and roses.

Then Walsh’s neighbor, a woodworker, rolled his power saw into his backyard, fired up that screaming bad boy and — poof — heaven was suddenly very noisy and covered in sawdust.

Walsh trotted over to let him know what his handiwork sounded and looked like from her side of the fence.

“He moved it back inside his garage,” says Walsh, who has since moved to Coto de Caza for unrelated reasons. “He just hadn’t thought about it. I think the moral of the story is speak up.”

Indeed, if everyone handled neighbor troubles in such a neighborly fashion, then city code enforcement officers, mediators and lawyers could busy themselves resolving bigger problems. And attorney, author and mediator Cora Jordan wouldn’t have had to write “Neighbor Law: Fences, Trees, Boundaries & Noise” and gone on to become an expert in a thorny area of the law that few want to touch, Jordan included.

“Lawyers cannot stand neighbor cases,” says Jordan, who practices law and mediation in Mississippi. They’re expensive, messy and can make judges cranky, she says. They don’t consider these tiffs to be the best use of the court’s time.

In fact, most lawyers will recommend professional mediation to clients with neighborhood spats. Mediators work with the squabbling parties to do what we all learned in kindergarten: talk and listen politely and try to come to a nice resolution. Still, it’s a tough lesson.

“The fact that people aren’t comfortable doing it is not a criticism of people,” says Robin Seigle, a trained mediator with the National Conflict Resolution Center in San Diego. “It’s just that we sometimes feel awkward about it. It’s a natural thing to avoid it.”

But some practice would be wise. Look around, says Culver City architect Alejandro Ortiz. Southern Californians are living in their backyards, Ortiz says. Much of his work involves blurring the lines between the inside and outside as homeowners shift living, dining and entertaining toward the great outdoors — and add ever more elegant landscaping to match.

“People have discovered the backyard as this wonderful place,” Ortiz says.

Too bad some of those people are the neighbors. Laura Smith of Hollywood knows that feeling. On her hillside street, a neighbor has taken to setting out peanuts every morning for the squirrels. Now it seems every squirrel in the county has gotten wind of the bounty, and the industrious little critters have proliferated and grown rather untidy as they do what squirrels do best: squirrel away nuts. They’ve poked and dug through Smith’s backyard planters and potted plants in an effort to hide their booty.

“At first I thought it was cute,” she says. But then the potted plants started dying, and Smith had to sweep dirt and wood chips off her patio every day. So she and her family tried some serious shooing. No luck.

“I’ve tried to scare them, but they don’t care,” she says. “They think they’re bigger than us.”

Now she’s researching squirrel repellents and hopes they work on skunks, since they too have started to dip into the peanut cache. But go to the neighbor who’s feeding the problem? Smith says she’s uncomfortable with that tack because she finds the neighbor intimidating.

Steve Willkomm understands completely. He has been in the code enforcement field for 20 years and is now code enforcement supervisor for the city of Whittier. Most of his department’s work involves approaching residents about issues their neighbors are too timid to raise.

“Most people resort to calling City Hall,” Willkomm says. In most California cities and counties, officials such as Willkomm have reams of codes at their disposal that cover nearly every legitimate offense. If the yard appears unsafe or even merely unsightly (tattered window screens are a hot topic in some towns), there’s probably a code to address it. Basic weed control and yard maintenance aren’t too much to expect, Willkomm says.

Most code enforcement officers try for cooperation before they start firing off citations, he says. Some homeowners do get offended and cling to an Old West this-is-my-land sensibility.

“That’s the argument we hear all the time,” he says. “But if they haven’t figured it out, they’re living in an urban area with 10 million other people.”

Still others, like Walsh’s neighbor, aren’t even aware that something they’re doing is offensive. One case that San Diego mediator Seigle managed involved a woman’s complaint that kids were peering over the fence from her neighbor’s yard. The neighbor was a leader in the Southeast Asian immigrant community, and his home was a gathering place. He was unaware that while adults visited, kids were out back being intrusive.

“It’s always good to assume the best about the other person,” Seigle says.

Mediators say it’s also helpful to meet face to face with a neighbor in a private place and to use that favorite tool of conflict resolution, the “I” sentence, as in, “I was wondering if you realized that your cat is using my new meditation garden for a litter box,” rather than, “Your filthy cat is a menace!”

In her book, Jordan even suggests using coy little conversation starters such as how-about-those-Lakers before leading into a chat about the killer bougainvillea that’s pulling down the fence. Another line she likes: “I’m sure you would want to know ”

And then there’s this old idea: Try to know your neighbors, so future disputes are limited.

Dawn Bonker can be reached at home@latimes.com.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.