- Share via

The first thing that catches your eye as you enter new Dedeaux Field — once you’ve navigated the ground floor of the parking structure, past the temporary batting cages in the construction zone beyond center field, down the path strewn with electric scooters, around “CONSTRUCTION ACCESS GATE #3” and onto the warning track of USC’s soon-to-be baseball home — is the actual field itself.

A new playing surface wasn’t something Trojans baseball players were clamoring for. They loved old Dedeaux Field and its charms. But plans for a football practice facility necessitated speeding up the timeline for upgrades on the half-century-old venue, and USC’s baseball program, with twice as many titles as any other school in NCAA history during that time, was told to make the best of it.

Of course, no one within the program was complaining about the prospect of a shiny new ballpark — least of all Andy Stankiewicz, the Trojans’ coach. But with a blank canvas on which to build a new version of Dedeaux Field, there was some upside. One is that every square inch of the park, down to the dirt, could now be given careful, meticulous consideration — with no expense spared.

“Every detail, every material was hand-picked,” says Scott Lupold, USC’s director of turf. He believes there will be no equal in the ranks of college baseball fields when his work is finished. The grade of the infield, he says, is perfectly flat. The gleaming green grass — Tahoma 31 Bermudagrass — is the finest on the market, the same you find in Dodger Stadium. And the dirt? You might catch yourself wondering if it’s dirt at all. “We were literally able to design every aspect of the surface how we wanted it,” Lupold says. As sports turf goes, this is his Sistine Chapel.

The rest of new Dedeaux Field requires a bit more imagination since it’s still an active construction site. A symphony of machinery fills the air on a recent Wednesday afternoon in early May as USC’s baseball team gathers for early batting practice. Swaying palm trees share the landscape behind home plate with a row of portable restrooms. Bulldozers lug loads of dirt across where the concourse will soon stand. Beyond right field, the towering skeleton of USC’s Bloom Football Performance Center takes shape in the distance.

USC’s new baseball stadium isn’t slated to open to the public until early 2026, but the Trojans began practicing here on the field in February, as soon as the sod had set. No one, by that point, could bear to wait any longer. Not after the better part of two seasons spent in exile, without a home field. It didn’t even matter that there was still no locker room in which to stash their belongings.

“These guys have spent a lot of time on a bus,” says Stankiewicz, who’s in his third season as coach. “They needed a light at the end of the tunnel.”

And sure, they made the best of those weekday rides to practice and the weekend series in Orange County. Some players said the time gave the Trojans a necessary chip on their shoulder. Most others tried to brush it off. (“Not having a home, it’s really not as tragic as it sounds,” one said.) But when the team entered through CONSTRUCTION ACCESS GATE #3 in February and onto the field they’d been promised, it felt like a weight was lifted.

To pitcher Caden Aoki, “it was genuinely like Christmas morning.”

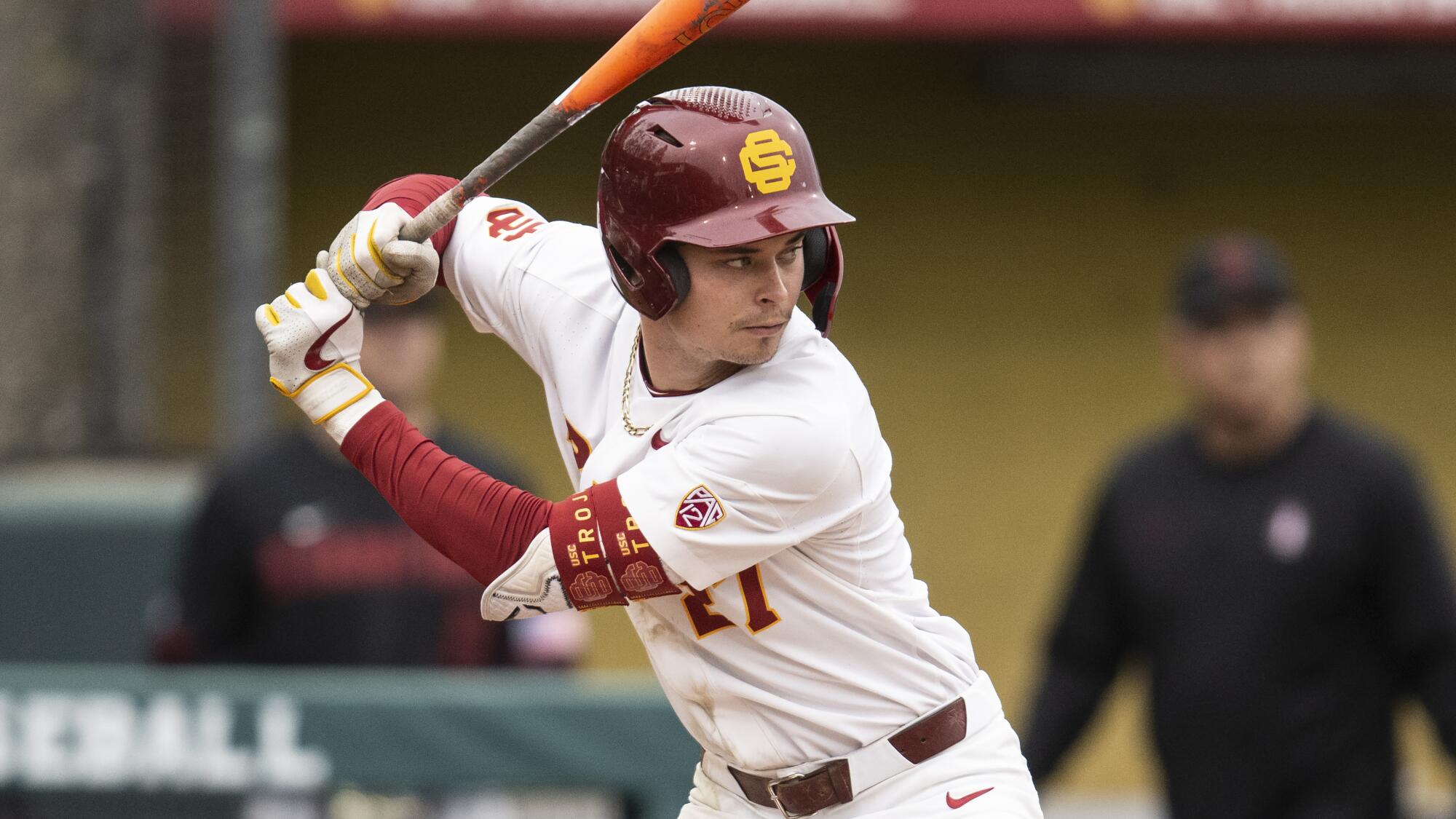

“We were all looking around at each other, and we all had big smiles on our faces,” said Ethan Hedges, USC’s star third baseman and closer. “It was a big moment for us.”

The moment was the first of many in what has felt to most around the program like a breakthrough season. The Trojans have since won 34 games entering Big Ten tournament pool play against Penn State on Thursday, good for their third straight 30-win season under Stankiewicz, who inherited a program that had just one such season in its previous 17 before he took over. Through one torrid stretch from March through early May, the Trojans won eight consecutive series, including one over crosstown-rival UCLA that rocketed them into the top 25.

An NCAA tournament berth seemed assured at that time, until USC finished out its regular season on a poorly timed skid, with losses in five of its last seven. The Trojans now find themselves firmly on the bubble, in need of at least a win or two in Omaha this week to secure a spot in the NCAA tournament for the first time since 2015.

No one around the program is downplaying what that milestone would mean now.

“It would mean — everything,” Hedges said. “That is everything we’ve been building towards.”

For the Trojans coach, it would be an especially important benchmark, three seasons into rebuilding a program that was once college baseball’s crown jewel. Yet Stankiewicz is also quick to remind that there are plenty of steps left in the process he’d set out to undertake. Early in his tenure as USC’s coach, he started using the slogan “brick by brick” to remind his team about the importance of incremental progress and building a foundation. Three years in, the catchphrase has become a part of the Trojans’ DNA, and the progress Stankiewicz promised is finally starting to show.

As USC’s coach sits in a barren concrete dugout, staring out at a soon-to-be state-of-the-art stadium still under construction, the metaphor all but writes itself.

“We want to build this thing for the long haul,” he says. “And to build a home, you have to build a strong foundation so it can withstand the weather. The same thing applies here. I want to be here for a long time.

“This is where I grew up. This is where I’d love to be. So we have to build this to stay strong for years.”

There wasn’t much of a foundation in place when Stankiewicz was hired as the coach. The turbulent tenure of his predecessor, Jason Gill, had been marred by unrest in the clubhouse and middling results on the field. When Gill was fired in 2023 after just two losing seasons and another shortened by the pandemic, speculation ensued over whether the USC job was really as illustrious as it once was.

Uncertainty over Dedeaux Field’s future amid prospective plans for the 2028 Olympics didn’t help that perception. Nor did the fact that two top candidates, Texas’ Troy Tulowitzki and UC Santa Barbara’s Andrew Checketts, pulled their names out of the running soon after USC expressed interest. Eventually, USC would land on Stankiewicz, a former major leaguer who grew up in nearby Cerritos and played at Pepperdine. As a kid, he sat in the stands at old Dedeaux Field as its namesake led the Trojans on a dynastic run, at one point winning five national titles in a row. He understood USC baseball — and still believed in what it could be at its best.

“Those teams were powerful,” Stankiewicz said. “They were strong. They were, at times, pretty intimidating. That was SC. We have to help restore that respect back here.”

So with that in mind, Stankiewicz stood in front of his team early in his tenure and tried to address the culture issue head on. He asked players what they thought other teams say critically about their program.

A few players raised their hands, Stankiewicz said, and shared versions of the same answer:

Soft. Entitled. Rich.

Others nodded along.

“The only ones who can change that perception is you guys,” he told them. “You write your own story. You want to change that perception, then go out there and don’t be soft.”

Stankiewicz brought in big-name alums such as Randy Johnson and Mark McGwire to speak to the team and help drive home that message. He wanted them to know that important people were paying attention, that it meant something to wear the uniform.

Right away, the team seemed to take that message to heart. After finishing last in the Pac-12 in 2022, the Trojans won 34 games in Stankiewicz’s first season and looked well on their way to ending their lengthy NCAA tournament drought.

Yet when the field was announced, USC was left out. The snub was a gut punch to the clubhouse.

“It felt like we could’ve easily broken through then,” infielder Bryce Martin-Grudzielanek said.

Instead, that fall, the Trojans would suddenly find themselves without a home field to play on.

Stankiewicz was assured when he took the job a year earlier that the city’s plans to build a new aquatics center on USC’s campus ahead of the 2028 Olympics would only displace the team for the 2028 season, after which the Trojans would have an upgraded stadium. But the Olympic plan fell apart. The athletic director who hired Stankiewicz, Mike Bohn, resigned the following May. And Jennifer Cohen, his replacement as USC’s athletic director, had made building a new football facility on the same property a priority.

Cohen met with Stankiewicz during her first week on the job to discuss plans. Not long after that meeting, he says he got a call.

“They told me, ‘Hey, we’re going to start on your new stadium,’” Stankiewicz recalled. “Well, I thought it was going to be after the year was over. But no, it’s, ‘We’re going to find a place for you to play that spring.’ That’s, umm, a little bit different. But we’re going to make it work.”

They spent the 2024 season playing home games primarily at Great Park in Irvine, making the best of the situation. They wrapped the ballpark’s columns in USC decor and draped the railings in cardinal and gold. For practices in the fall, they bused each morning to El Camino College in Torrance and crossed their fingers that the gates weren’t locked.

The circumstances were not ideal. But after a slow start, the Trojans would finish the season on a tear with wins in nine of their last 10 games.

“The mindset he’s taught of us, just about how it doesn’t matter what we have or who we have,” Hedges said. “It’s just about showing up every day with 100% of what you have. Like, OK, we didn’t have a field. So what? You can’t use that as an excuse.”

Still, there was no avoiding the ripple effects of that reality. It meant explaining to recruits and prospective transfers that they’d be without a field to play on or batting cages to hit in or a locker room to retreat to. It also meant losing a few of their own players to the transfer portal who “didn’t want to keep getting on a bus” for another season.

Stankiewicz understood. He didn’t hold it against any of those who couldn’t stay patient. Those who did stay the course, sticking it out through two nomadic years at USC, say something different has taken hold within the team in this third season.

“A team is very hard to cultivate, like an actual team, where every single person is bought in,” Aoki said. “I feel like I would be lying if I said every single person was bought in the first two years I was here. But I can say with 100% certainty that everyone here is bought in. That makes a difference.”

It doesn’t hurt, either, to have unearthed a two-way star in Hedges, who led the Big Ten in saves (nine) in his first season as a pitcher while hitting .346 with 12 home runs and 54 RBIs to anchor USC’s bullpen and batting order. And to think, that breakout had come entirely out of desperation for pitching depth.

“Ethan Hedges, jack of all trades, master of everything,” Aoki said with a laugh.

Others have made their own major leaps. Transfer first baseman Adrian Lopez saw his average skyrocket from .223 as a Long Beach State sophomore to .333 as a junior at USC, where he’s hit nine home runs. Infielder Abbrie Covarrubias is hitting .300 as a sophomore after slashing .232 as a freshman, while catcher Andrew Lamb is hitting .344 with an OPS of 1.031, both of which would lead Big Ten catchers if they qualified.

USC’s pitching staff, by far the biggest concern coming into the season, has been a pleasant surprise, thanks to Hedges, who hadn’t pitched since his days at Mater Dei High, as well as a bevy of unproven relievers.

“It would be really hard for any team in the country to do what we’re doing,” said Aoki, who has a 4.54 ERA with a 5-4 record this season. “But we’re doing it because every single person who has stepped up on that mound has stepped up and really flourished in their own right.”

Whether that’ll be enough this week to secure an NCAA tournament berth remains to be seen. But the foundation for something even bigger and better has undoubtedly been set at USC, even if there are a few more bricks left to be laid.

More to Read

Fight on! Are you a true Trojans fan?

Get our Times of Troy newsletter for USC insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.