Conquering the Grand Canyon

- Share via

GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK — There are six of us, all women, sitting in the dusk about 1,300 feet above the Colorado River. The rock “temples” of the canyon surround us, Shiva and Isis to the left, Brahma and Zoroaster to the right. All eyes are trained on a maiden moon, draped in gossamer clouds, hanging in the darkening sky. No one says a word. Everything is just the way we like it.

Tucked away safely in my mind and captioned “Six Women Gazing at the Moon on Plateau Point,” this Ansel Adams moment somehow captures how the Grand Canyon affects people. Maybe awe of its grandeur strips away human egotism, reconnecting us to our small place in nature’s scheme. Or maybe, as Melanie Miles, the leader of our little band of hikers believes, people come here for different reasons and take away whatever it is they need.

Miles is an instructor with the Grand Canyon Field Institute. Like other field institutes associated with U.S. national parks, this is a nonprofit educational organization that offers in-depth outdoor programs on ecology, geology, photography, archeology, wilderness survival and other pursuits “in the field.” Most are reasonably priced (mine cost $355, not including food, equipment and accommodations on the canyon rim) and involve hiking and camping. (The park service’s interpretive programs, in contrast, last only a few hours and tend to stick to the heavily traveled South Rim.) “The field institute fills a need the park can’t by providing back-country trips for people who don’t want to do them on their own,” says Judy Hellmich, head of the Grand Canyon’s interpretive program.

Some field institute programs are easy, perhaps for families. Others are for experienced wilderness trekkers. My “Women’s Introductory Backpack: Colorado River” program was based on a recognition that many women experience the wilderness differently from men. Programs like this one are intended to teach women their own brand of self-sufficiency in the outdoors.

Miles, a 5-foot-5, 110-pound Englishwoman who fell in love with the canyon 16 years ago on a cross-country bus trip, swears she has to use a clipboard and lift something heavy at the beginning of coed programs to gain the confidence of the men. She remembers only one man bursting into tears at first sight of the Colorado River after the hike down to the canyon bottom; women do it all the time.

But there I will leave it, because the story of my trip--seven miles down South Kaibab Trail from the South Rim to Bright Angel Campground at canyon bottom, then back up Bright Angel Trail to Indian Garden and the rim again--hasn’t anything to do with men. It has to do with six women between 35 and 55 and the goals they met by taking part in the program.

The trip wouldn’t impress canyon veterans or lovers of extreme sports. It was a Grand Canyon classic, down and up trails trod by thousands, with a two-night stay at the Bright Angel Campground and a final night at Indian Garden Campground, halfway up the South Rim, to break up the tough climb out. Only 5% of the roughly 5 million people who visit the Grand Canyon every year go below the rim, and only about 10% of those make it to the river.

The canyon is a vertical world, extremely hard to hike. The South Kaibab and Bright Angel trails, which lose about 5,000 feet in elevation from rim to bottom, severely tax lungs, knees and thighs. In the stiflingly hot summer, people blithely embark from the South Rim without enough water, expecting to reach the river and climb back out in a day. Some turn around partway down, exhausted. More than 400 people were rescued in the Grand Canyon last year, a national park system high.

The women in my group would make it all the way, with dignity, Melanie assured us. She surely would. At 37, Melanie has trekked from rim to river to rim at least 75 times, and between hikes works as a Colorado River rafting guide.

The first day was spent largely in a classroom at the field institute headquarters. We had filled out lengthy health questionnaires and knew what to expect because the field institute brochure carefully rates the difficulty of its trips (ours was a 3-plus on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the toughest). In class, we shared our reasons for taking part in the program. Melanie, who looks more like an elf than an Amazon, says women tend to want to talk about an impending challenge as a way of processing their emotions and getting support, while men just want to go out there and get through it. But there was little fear or soul-searching in my group.

Becki Fink, a pharmacist from Tucson whose husband stayed on the rim, said she wanted to gain self-sufficiency in the wilderness. Anne Douville, from Oakland, was on an extended vacation in the Southwest, preparing in the Grand Canyon for backpacking in Zion National Park. Kathy Gohl, a freelance editor from Vermont, had come to see how hiking in the West compares with hiking in the East. And Judy Jagla, from Sedona, Ariz., was an inveterate walker who felt the need to get more comfortable with camping out. I just wanted to make it down and back again under my own steam, find a place to wash my hair at the bottom and take notes for this story.

After the introductions, Melanie talked about health and safety, especially how to avoid heat exhaustion and hypothermia. As hikers descend to the bottom, the temperature rises as much as 20 degrees. And there is no fresh water on South Kaibab Trail, meaning we each had to fit at least three quarts of water in our packs. We brought all our gear to the session and spread it out around us so Melanie could help us assess what we actually needed. Comparing equipment was instructive.

“I can’t believe how light your tent is.”

“That sports bra looks comfortable. Where did you get it?”

“Look, Kathy’s got freeze-dried Thai noodles.”

Then Melanie displayed the contents of her pack, an inspiration to us all: sleeping bag, medical kit, headlight, map, cookstove, food, eating utensils and a plastic ground cover (used as a tent when weather prohibits her from sleeping under the stars), all in less than 30 pounds. She would start out wearing most of the clothes she needed for the four-day hike. She had no use for shampoo because she didn’t plan to wash her hair.

As we jettisoned extraneous pillows and espresso makers, Melanie gave us useful tidbits of advice. These were the sorts of things Martha Stewart might know if she went into the wilderness but no one had ever shared with me before: how to dress a blister; the benefits of taking off your hiking shoes and elevating your much-abused feet at rest stops; keeping snack food handy; getting your head wet when overheated; and the danger of long toenails on boot-bound feet.

The next morning we shuttled to the trail head, about five miles east of Grand Canyon Village.

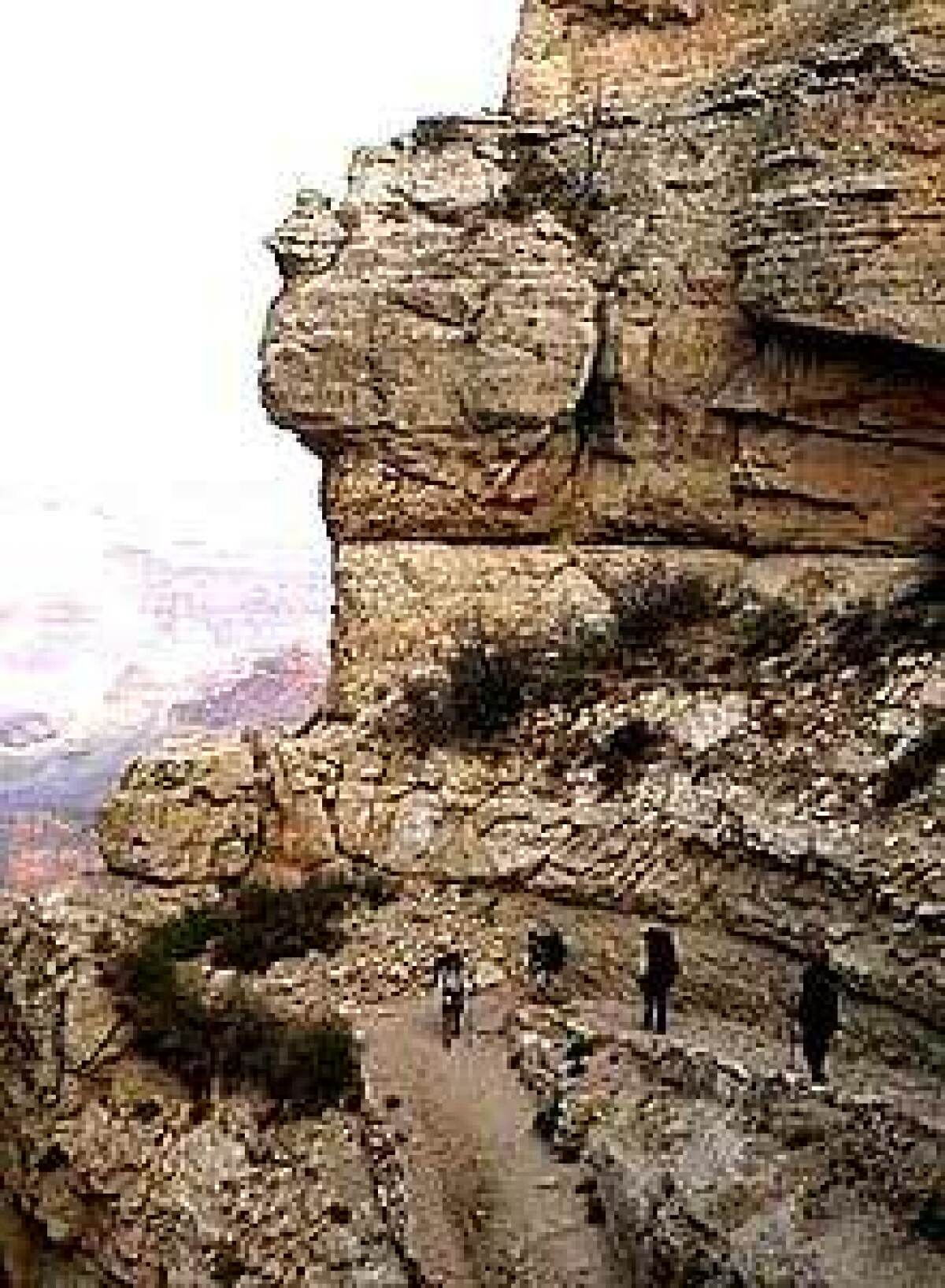

South Kaibab is steeper, shorter and newer than Bright Angel Trail, slicing through all the layers of the canyon’s geologic club sandwich in its dramatic descent. Melanie pointed out the different kinds of rocks as we passed them--Kaibab limestone, Toroweap formation, Coconino sandstone, Hermit shale, Supai group, Redwall limestone, Muav limestone, Bright Angel shale and Tapeats sandstone--and taught us two mnemonics to remember them in order: “Know The Canyon History; Study Rocks Made By Time” and “Kissing Takes Concentration; However, Sex Requires More Breath And Time.”

Most of us had doffed an outer layer of clothes by the time we reached Ooh Aah Point, three-quarters of a mile below the rim, where we all posed for pictures on a rock throne, dangling our feet over a cliff. We debated whether going down was harder than going up, put our legs in an easy third gear while crossing the relatively flat Tonto Plateau and ate lunch at the Tipoff, where we could plainly see the Coconino layer on the North Rim, which looks like a dirty ring around a bathtub.

From there South Kaibab got steeper as it wound downward, burrowing through a short tunnel before reaching the Colorado River at the Kaibab Bridge. By then it was late afternoon, and about half the group wouldn’t have walked down another hill if there had been a forest fire behind them. I was in the other half, all downhill racers, happy as long as we didn’t think about the prospect of the trip back up. Fortunately, all that remained was to put one foot in front of the other for a mile or so until we reached the campground, strung out along the west side of rushing Bright Angel Creek and, behind it, like a set for a Greek tragedy, a looming wall of Vishnu schist, the 2-billion-year-old red-black rock at the bottom of the canyon.

(Explorers at the turn of the century tapped their interest in comparative religion by giving names to Grand Canyon landforms. So on the North Rim, there are buttes named for the gods and holy men of Hinduism, Buddhism and other religions. The ancient glinting rock at canyon bottom is named for Vishnu, the Hindu preserver of the universe.)

Most of the women in my group reverted to domestic habits by setting up camp immediately. But Melanie and I bathed in the creek with our clothes on, washing out socks and T-shirts at the same time.

We cooked our dinners while the sun set: Mine was macaroni and cheese, followed by cookies and a cup of chamomile tea. Melanie showed us how to clean our bowls without dumping out any scraps, prohibited in leave-no-trace camping. The procedure involved licking the bowl, then making tea in it. Once you finish the tea and the leftover dinner crumbs in it, the bowl can be packed.

That’s the only thing Melanie ever did that disgusted me. But after dinner she made up for it by reading to us from “Grand Canyon Women,” a book by Betty Leavengood. The chapter she chose was about pioneer Colorado River runner Georgie White Clark, who twice drifted down the river in the ‘40s in nothing but a bathing suit and a life preserver. Her commercial river trips were notoriously hair-raising, with unchanging menus of boiled eggs, canned stew and beer. Nonetheless, when she asked her clients how they were doing, they were expected to reply, “Everything is just the way we like it.”

We spent the next day visiting beautiful old Phantom Ranch, across the creek from the campground, and hiking into Phantom Canyon, where we found a deep hole for skinny-dipping. That night, some went to the ranch for beer and a ranger program on 19th century Colorado River explorer John Wesley Powell. But I stayed back at camp, doing nothing except wondering when I’d ever get back to this otherworldly place.

The following day we said goodbye to the river and turned onto Bright Angel Trail. Desert bighorn sheep followed our progress from high rocky perches, and after lunch we explored an ancient cliff dwelling just above Devil’s Corkscrew. We settled in at Indian Garden Campground, ate early and then walked out to Plateau Point.

We were tired, dirty and uneasy about the next morning’s prospect of hiking up the final segment, the hardest and steepest of the trip. Everyone got up early and broke camp quickly. It was only a 4.6-mile hike, but we wanted to get the ordeal over with. Our packs were a little lighter than they had been going in because of the food we’d consumed, so I started out briskly, second in line behind Becki.

She never let up, but when I hit Jacob’s Ladder, a wicked set of switchbacks carved along a fault line in the Redwall limestone, my pace slowed to a stagger. My pack felt like the weight of the world, and, with each step, every muscle in my body cursed me. Anne, Judy and Kathy soon passed me by. I had only the consolation of impressing day hikers headed down to Indian Garden. Melanie stayed behind me, to try to restart my heart if I collapsed. But I kept going and finally celebrated with my comrades at the top.

I’m not sure I finished with dignity, but, thankfully, time has made me almost forget the rigors of the hike out. But I do remember how it feels when six women sit together in stillness looking into the Grand Canyon and that I made it down to the bottom and back. They can put that on my tombstone, which I’d like to be made of Vishnu schist.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.