A splendid isolation

- Share via

Aboard the Aranui 3 — As dusk fell on Papeete, Tahiti, we stood on the aft deck, sipping Yoyo the bartender’s infamous rum punch. Soon the new Aranui 3 would set sail on a 15-night voyage to the remote Marquesas Islands. With America plunging into war, here we were, 4,000 miles from Los Angeles, captive travelers on a passenger freighter headed for dots on the map in the South Pacific with no CNN, no newspapers. Was I on the freighter to paradise or a ship of fools?

I had another rum punch.

We eased away from the dock in darkness, past the Paul Gauguin, a luxury cruise ship that would soon depart on a South Seas cruise. No casino or room service for us, though. We were adventurers, a backpack-and-Teva- sandals crowd.

By our return to Papeete, we had hiked through intense heat and humidity to meae (ancient tiki sites), sampled popoi (breadfruit poi, a little less like library paste than the Hawaiian variety), bounced along a mountain road in the back of a pickup and survived treacherous whaleboat landings safe in the arms of the Aranui’s tattooed sailors.

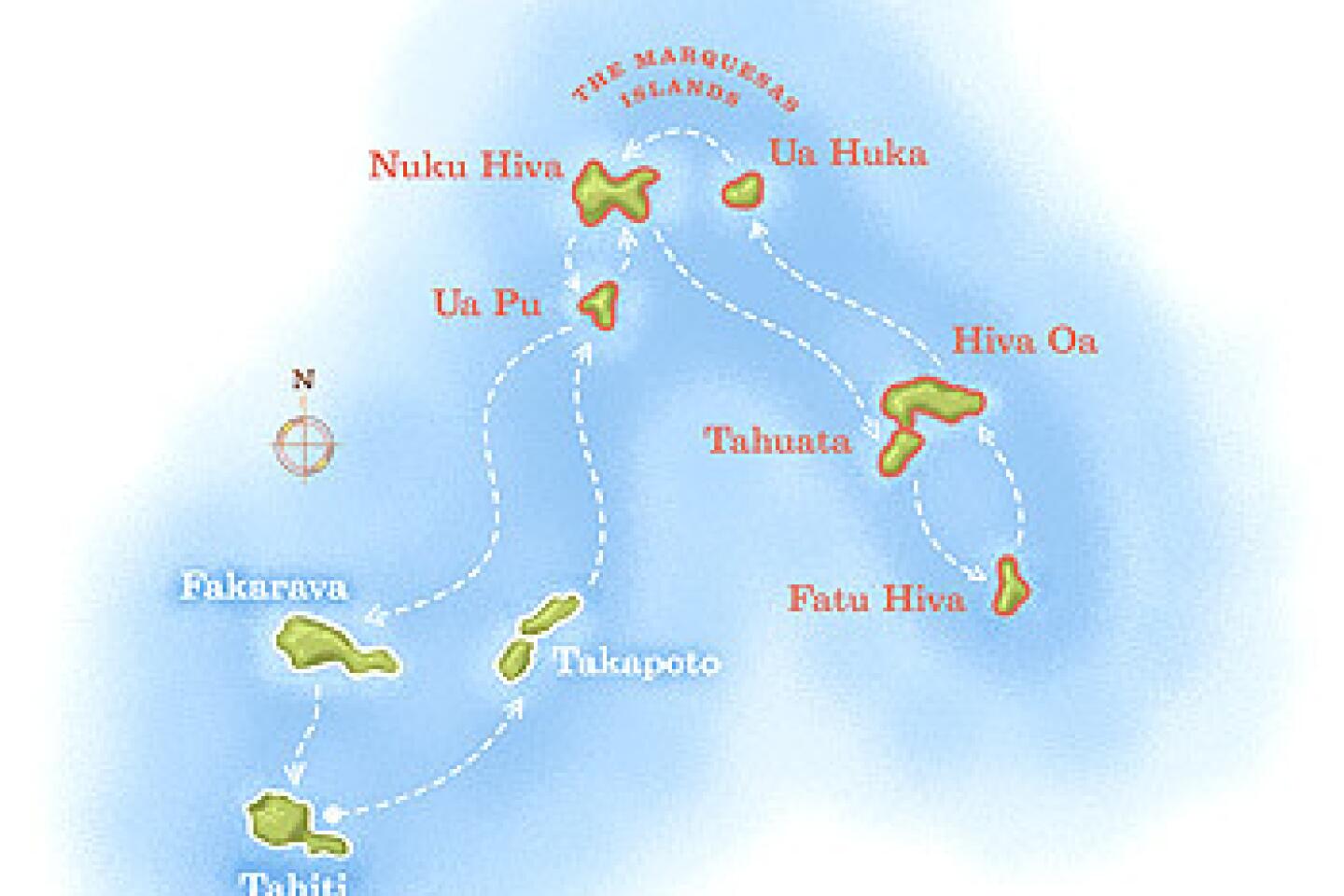

Our route took us from Papeete to the Tuamotu Archipelago, through the Marquesas, back to the Tuamotus and to Papeete. Prewar, when I’d booked, the lure of the South Seas without cruise ship glitz was irresistible. Once war was reality, I told myself no place could be safer than French Polynesia.

Sun streaming through the porthole our first morning at sea awakened me at 6:30. The ship’s gentle rolling had been a sleeping pill. On came the shower with a nice strong burst. Cold. A bad omen. (An engineer had pushed the wrong button, a one-time misstep.)

Glitches were inevitable on this, the second voyage of the Aranui 3, a Romanian-built ship of French registry that’s bigger (386 feet long) and fancier than its two predecessors. The elevator refused to stop on our deck. The water sports platform wasn’t working because the cable had snapped on the inaugural voyage when the platform was lowered.

But the Aranui is no mere ship, to be judged by its amenities. It is a great experience, the most endearing part of which is the multilingual crew of 52, most of them Tahitian. There were those burly tattooed sailors and the charming Vaihere, who greeted us daily, guided us on tours and toted around a case stuffed with French Pacific francs to lend. (Credit cards haven’t caught on in the Marquesas, and the few ATMs may be out of money.) The day we left, crew members kissed passengers — and not for tips, which were optional and anonymous.

Intrepid adventurers

We were 70 voyagers leaving Papeete and would pick up a few more cabin passengers in the Marquesas as well as some “deck passengers” traveling between islands. The air-conditioned ship accommodates 200 in cabins and a dormitory, twice as many as the Aranui 2, but a number of war-wary travelers had canceled, leaving 20 Americans, 51 French and a sprinkling of Germans, Swiss and Dutch. It was a surprisingly mature crowd for such a rigorous trip. The Americans included six delightful Elderhostelers.At sea the first day, cruising at 17 mph, we had time to explore the ship and learn the rules: Smoking allowed only on deck. Laundry service was provided in upper class; the rest of us had to fight over two washing machines and one dryer. Cabin keys were to be left at reception whenever disembarking so no one would be left ashore.

My standard cabin (7 by 16 feet) was basic but comfortable, with two bunks and good storage. Deluxe cabins and suites are spacious and attractive, with queen-size beds, tubs and sitting areas. Suites have balconies. Some passengers who had traveled on an earlier Aranui weren’t completely thrilled with the new, improved model. “The Aranui 2 was a cargo ship that took passengers,” one said. “This is a passenger ship that takes cargo.”

The décor was odd for a South Seas ship, especially in the spacious, seldom-used lounge. It was a sea of rose-colored tub chairs on a violently violet carpet, reminiscent of a public room in an airport hotel.

The French soon were soaking up the sun by the freshwater pool, women who should have known better baring bosoms and most of their bottoms. The Americans were likely to be under cover and under their Tilley hats.

The dining room, which accommodates 200 at a single seating, family style, is airy and pleasant. The food was heavy, with lots of meat and sauces. In a nod to the French, lunch is a full meal, no salad or sandwich options. Fish, green vegetables and salads were scarce, and menus could be bizarre. On what I dubbed “white night,” we had cream of cauliflower soup, blanquette de veau, rice and floating island, a meringue-topped custard. Bar drinks were pricey ($9.50 for the exotic, $2.50 for a cola), but lunch and dinner included veritable waterfalls of wine, gratis.

Traditional Marquesan food was served at four lunches ashore in inviting open-air restaurants, including Chez Yvonne on Nuku Hiva, where women in saffron yellow pareus (sarongs) served us fried shrimp, breadfruit fritters, lobster, poisson cru (raw fish marinated in coconut milk) and pig baked in the ground. Although we never lacked for calories, the promise of lobster at one onshore buffet and the ensuing stampede prompted one passenger to say, “If I slipped to my knees, they’d have me carved up and eaten in no time.”

Exploring the islands

Two days after leaving Papeete, it was land ho at Takapoto in the Tuamotus, an archipelago of coral atolls about 345 miles northeast of Tahiti. We packed our swimsuits, sunblock and water bottles and piled into the whaleboats. Onshore, villagers draped heis (Polynesian leis) around our necks as a little ukulele-and-guitar band played Polynesian music, which is a bit more hyper than hula.The heat was oppressive (it was summer south of the equator), and those forgoing the beach hike (including me) enjoyed a 10-minute whaleboat ride to a palm-fringed turquoise lagoon to swim and picnic. We passed little huts over the water where black-pearl farmers graft bits of Mississippi River shell into oysters to annoy them into creating pearls, a thriving industry. (Too thriving. Overproduction is a problem.) Still, although prices are better here than in Tahiti, pearl vendors who had set up tables under a thatched pavilion were asking in the high hundreds for good pieces.

Having downed a few Hinanos — Polynesian beers — some picnickers headed for the restrooms, inside a shack with three blue doors that almost closed. Outside each was a blue barrel of water and a bucket. Fresh water was scarce.

Another full day at sea brought us to the Marquesas, a group of ruggedly beautiful volcanic islands about midway between Hawaii and New Zealand. Relatively few tourists visit the six islands, whose population totals 8,000. Although other cruise ships sometimes call at some of the islands, the Aranui is the only passenger-oriented ship making regular trips — 16 a year — to all the populated islands. “Civilization” has encroached on these islands, with their boxy little corrugated-roof houses, only slowly. Satellite TV dishes and four-wheel-drives abound, but billboards are unknown.

Because most islands have no dock, we would descend the ship’s ladder and, putting our trust in those sea-savvy sailors, be hauled into and hoisted out of the whaleboats. Sometimes the boat thwacked against the rocks as a passenger teetered on the edge, waiting for the order to jump.

The routine became familiar during our nine days in the Marquesas. After buffet breakfast, which was from 6:30 to 8:30 (although those arriving at 8 found les crumbs), we would pack our gear and head for shore, where we were greeted with flowers and a “bonjour” or a ka o ha nui. Typically there were musicians and, often, traditional dances and a table laden with tropical fruits. Artisans would set out their handicrafts — lovely carved bowls of rosewood, acacia and teak, tikis (some on Viagra), shell jewelry, colorful pareus. Some passengers enjoyed the shopping; others found it too time-consuming.I had mixed feelings about all of the above. Although the islanders were almost universally friendly and the arrival of the Aranui was eagerly awaited, I’m uneasy in oh-look-aren’t-they-quaint situations. We came, we saw, we photographed, we bought. Presumably, everyone was happy. Once I watched as the young men who had just danced for us disappeared, quickly doffing the tapa cloth in favor of surfer shorts.

We called at Ua Pu, Nuku Hiva (where “Survivor” was filmed last year), Hiva Oa, Fatu Hiva, Tahuata and Ua Huka. By journey’s end, it was sort of “if this is Tuesday, it must be Ua-Oa-Huka-Pu.” But the beauty of the islands and their cobalt blue waters almost defies description — green spires capped with clouds, valleys ablaze with flowers, trees dripping with mangoes.

We saw sites where human sacrifices once were made in the name of religion, and we saw little steepled churches. (Ninety percent of Marquesans are Catholic.) We watched men in leaf skirts grunt and groan on all fours in the pig dance, homage to an animal that early Marquesans revered.

We learned about nonos — pesky little flies that have a wicked bite — and about noni, a fruit that has supplanted copra (dried coconut meat) as the islands’ chief export. Its juice, marketed by a Utah company, is an alleged body-bolstering elixir that smells like Camembert. The Aranui takes it in blue barrels to Tahiti for processing.

The ship offers no entertainment save the Aranui Band (a few crew, sometimes including the captain) and impromptu concerts on deck whenever two or three crew members have downtime. The real show was the loading and unloading of the 3,000 tons of cargo we carried — cars, chicken, cement. At ports, locals lined up with shopping lists of staples.

Eager for war news, we relied on passenger Jerry’s shortwave radio to pick up the BBC. “This is the first war we’ve missed since the Revolution,” one Elderhosteler said. But in no time we’d be immersed in our reality, which might be a Marquesan woman showing us how to peel the inner bark of a mulberry tree and pound it thin into tapa. Or listening to the songs of schoolchildren — some wearing pareus, some Old Navy.

When the Aranui says casual, it means it. The night we were bidden to meet captain and crew, a few women wore dresses, thinking reception. But captain and crew appeared in T-shirts, took a bow and left. At meals, anyone was welcome to take an empty seat at the table of Capt. Taputu Mapuhi.

Fellow travelers included a Dutchman who’d given up his medical practice to return to university to “seek wisdom,” a San Franciscan who ate only raw food and was happy to proselytize, a retired Navy captain from North Carolina and three journalists from England, Australia and Germany. The French tended to keep to themselves, as did the Americans. C’est la guerre? No, said an Aranui insider, “we always have problems with French and Americans.”

Things I learned: The 20-minute hikes to villages were always longer and steeper than advertised. Every day is a bad hair day in French Polynesia. I should have taken more film and a hands-free carryall to tote gear ashore. Traveler’s checks, largely anachronistic elsewhere, are welcome and useful here.

Among places I’ll remember is Nuku Hiva and its verdant Taipivai Valley, with acres of coconut palms and a fiord-like river flowing into the bay. It was here in 1842 that author Herman Melville, having jumped ship, spent six weeks under the watchful eyes of the cannibalistic Taipi tribe, an adventure he glamorized in his novel “Typee.” I’ll remember, too, stars blazing in black skies, blue-pink sunsets and a rain right out of W. Somerset Maugham.

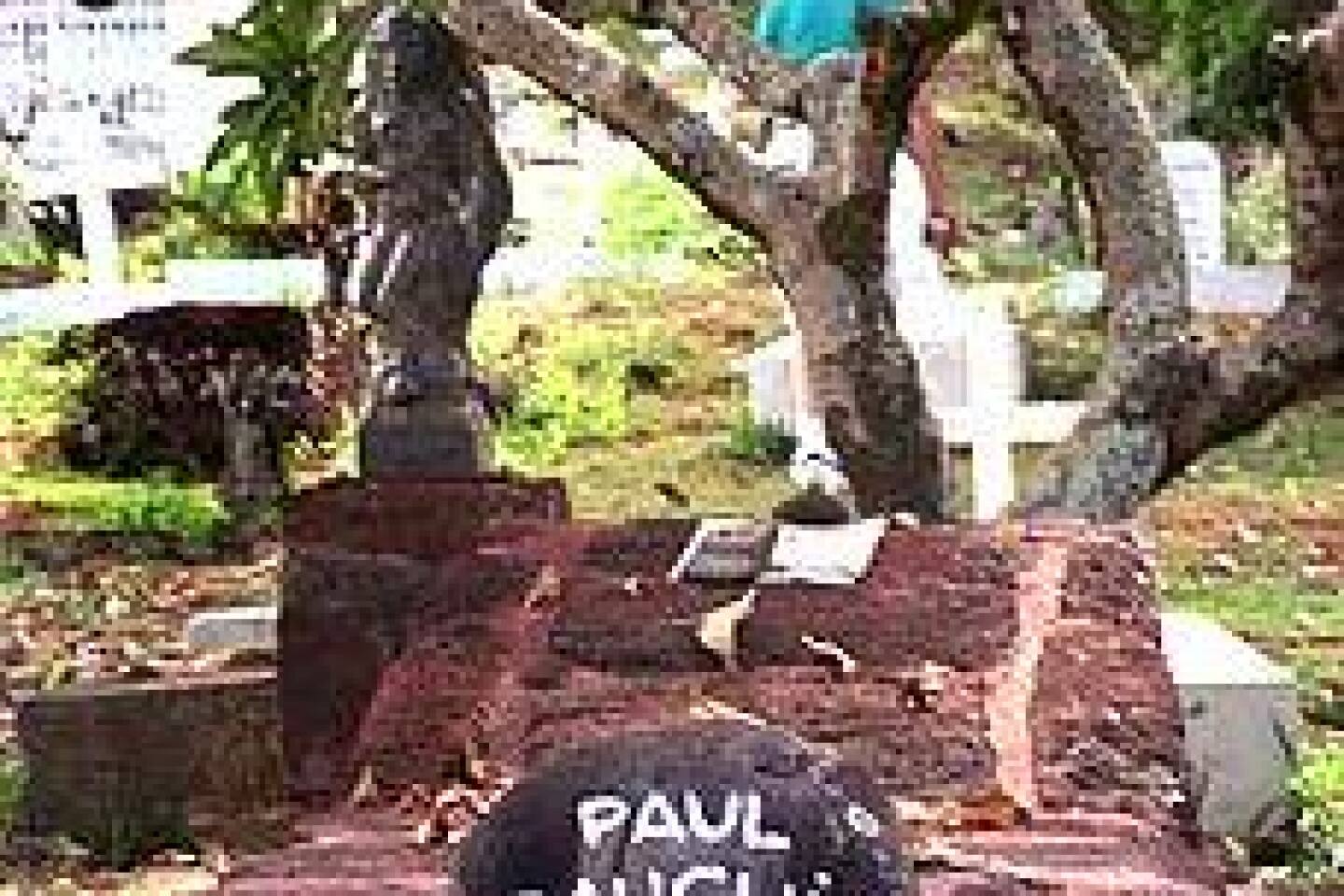

One of the most anticipated excursions was to Atuona on the island of Hiva Oa. There, at a cemetery high on a hill, amid weeds and rusted crosses, are the graves of Paul Gauguin and Belgian cabaret singer Jacques Brel, who lived on Hiva Oa before his death in 1978. Gauguin, seeking a savage element to reignite the artistic fires within, spent the last two years of his tortured life in Atuona. Unfortunately, the replica of his infamous “house of pleasure” has been torn down, but a new one is being readied for May festivities marking the centennial of his death. (The May 3-to-18 Aranui voyage will be a Gauguin-themed cruise.)

Fifteen days on the Aranui is a bit long and somewhat repetitious. As one passenger observed, “Some people wish it would never end. Some people say, ‘Thank God it’s over.’ I’m in between.”

I, too, was in between.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.