Hindenburg partial replica is highlight of Zeppelin Museum in Germany

- Share via

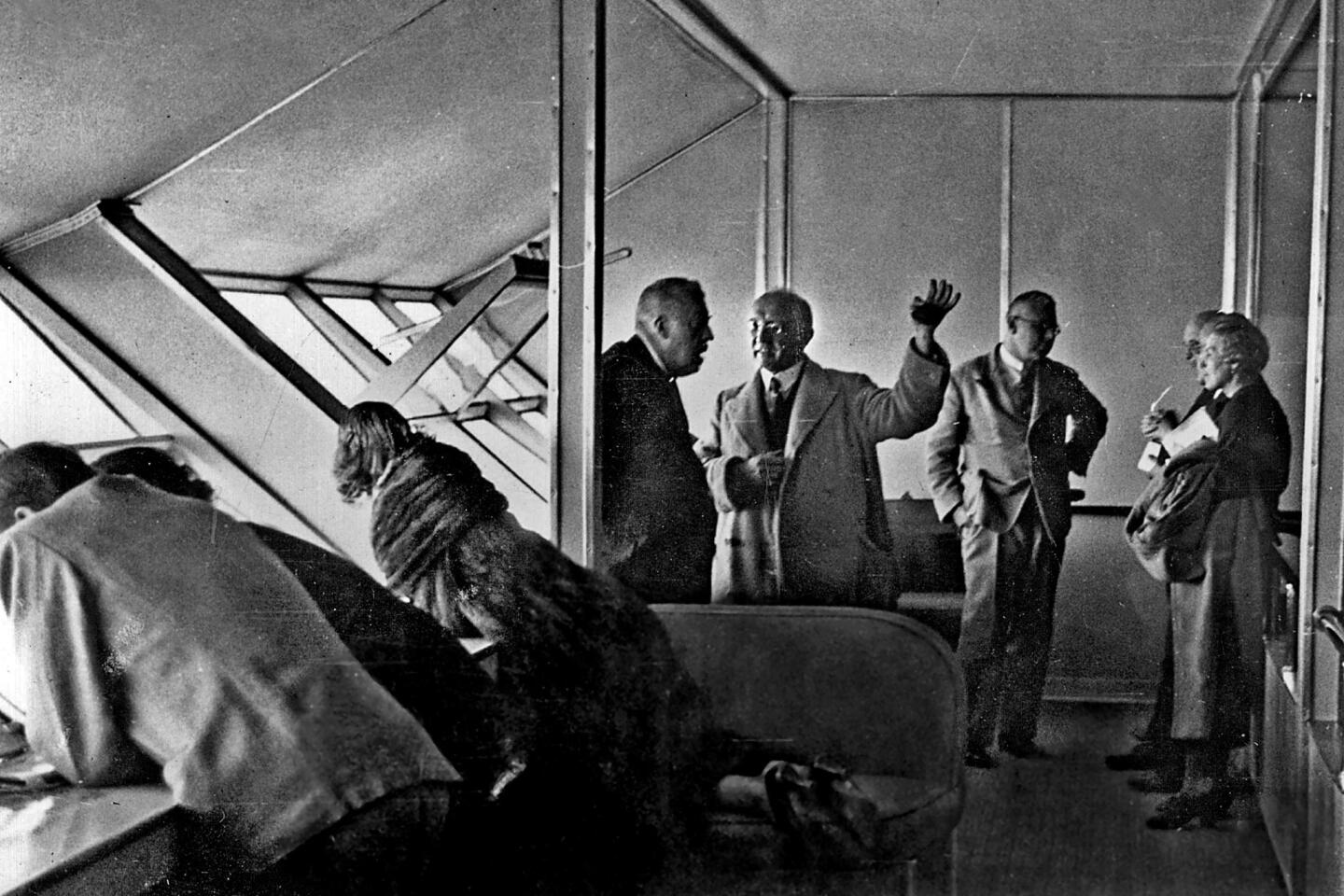

FRIEDRICHSHAFEN, Germany — I am looking at a piece of the Hindenburg — or, rather, its replica: its lounge, reading and writing room, passenger cabins and smoking room (yes, there was one) and bar. It’s part of the Zeppelin Museum, in the former Hafenbahnhof, or Harbor Railway Station, a striking Bauhaus-style building completed in 1933 in Friedrichshafen, the birthplace of the zeppelin.

The museum is chockablock with zeppelin memorabilia, but its centerpiece and what drew my wife, Laurel, and me here in October, is this full-size replica of the starboard section of the Hindenburg that’s more than 100 feet long. It was created from photographs and original plans, using, in part, original tools. Familiar as I was with Hindenburg history — my father had been a passenger on one of its eastbound flights to Germany — entering these re-created spaces was a revelation.

When the hydrogen-filled Hindenburg exploded and burned while landing at the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, N.J., on May 6, 1937, as it concluded its first crossing of its second season, the zeppelin era abruptly ended.

Zeppelins are so long gone from the public consciousness that it’s easy to forget that 75 years ago the Hindenburg offered a comfortable, stylish, swift (two days) way to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Its huge size turned heads wherever it flew. It was a magnet for celebrities and on the cutting edge in its day.

These airships are only distantly related to the blimps we see today hovering over stadiums. Those are basically elongated balloons filled with nonflammable helium, with a control car suspended below. Zeppelins had rigid frames and were filled with flammable hydrogen.

The great silver skin of the zeppelin’s underside looms over the main exhibition space at the museum. A stairway leads us up to B Deck, where we see one of the lavatories; from there stairs lead to A Deck and into the spacious lounge, furnished with minimalist Bauhaus tables and chairs. Walls are covered with balloon silk; on them Otto Arpke had spray-painted an intricate map of the world showing the paths of famous explorers, the Hindenburg’s route between Germany and New Jersey, the route to Brazil shared by the Hindenburg and its sister airship the elegant Graf Zeppelin, and the route of an ocean liner crossing from Germany to New York City

Adjacent is the reading and writing room, furnished with a pair of double desks and a letterbox. Wall paintings, also by Arpke, trace the development of mail carriage through the years — ending, of course, with the zeppelin. Outside both these rooms is a promenade with benches and slanted windows. We look down on exhibits in the hall below, but the 50 Hindenburg passengers would have seen towns, the ocean and the occasional ship as, weather permitting, the airship sailed at an altitude of 650 feet. Some windows opened to let in the cool Atlantic breezes.

Also on A Deck are re-creations of a few of the 25 small passenger cabins, similar to rooms in railroad sleeping cars, with upper and lower berths, fold-away sink, small writing desk and collapsible stool. The aluminum berth ladder, riddled with holes to minimize weight, looked like Swiss cheese. One room was made up for sleeping, another set for day use, with the upper berth folded away and the lower converted to a sofa.

The dark parts of the Hindenburg history — particularly the Lakehurst tragedy that incinerated the airship in 32 seconds and left 35 dead among the 97 passengers and crew, and its use by Hitler and the Third Reich as a propaganda tool — receive their due. Chief Radio Officer Willy Speck was among the Lakehurst casualties, and his ember-scarred uniform jacket is on display, sobering testimony to the tragedy.

Other memorable exhibits: a wall-sized case with models showing comparative size. The Hindenburg is edged out by the Queen Mary (1,020 feet versus 803 feet) but dwarfs the 246-foot-long Zeppelin NT (Neue Technologie, or New Technology, completed in Friedrichshafen in 1997) and a slightly longer Lufthansa wide-body jet. There’s hardware, most notably one of the Graf Zeppelin’s engine gondolas. All aspects of zeppelin history, from polar exploration to extensive military use to touring, are covered.

We came to Friedrichshafen for the Zeppelin Museum but also found an engaging small city on the shores of Lake Constance, or the Bodensee, shared by Germany, Switzerland and Austria. Trans-lake ferries buzz in and out, docking right behind the museum, where the century-old, impeccably restored paddle steamer Hohentwiel also sometimes calls. We sampled apfelstrudel mit schlag at one of the many cafes on the lakefront, watching the ferries come and go; as the afternoon grew chilly we wrapped ourselves in the blankets provided.

Then we returned for a fine dinner in the woody, traditional dining room at our hotel, the Buchhorner Hof. Built in 1898, it has seen the entirety of the zeppelin era, including the current Zeppelin NT, which is pictured flying above the hotel on its brochure cover. Perfect, we thought.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.