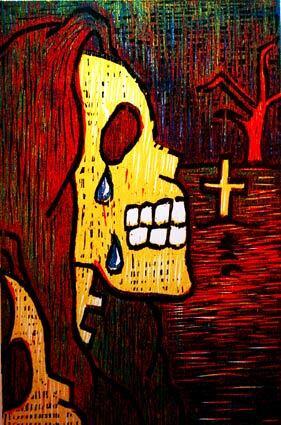

Marisol Gomez is the creator of Recuerdos (Memories), a wood engraved print. In Mexico and other Latin American cultures, death isnt merely a depressing curtain-closer but rather a passage into a kind of parallel reality whose inhabitants enjoy the same pleasures and suffer many of the same tribulations as the living. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

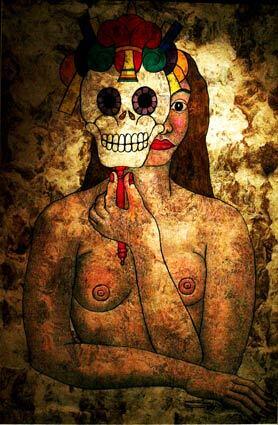

La Mascara is another work by Octavio Bajonero Gil, who not only is a crucial donor to the National Museum of Death but one of Mexicos most esteemed graphic artists. Bajoneros collection now fills six galleries of an elegantly restored 17th century convent in Aguascalientes, about a six-hour drive northwest of Mexico City. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

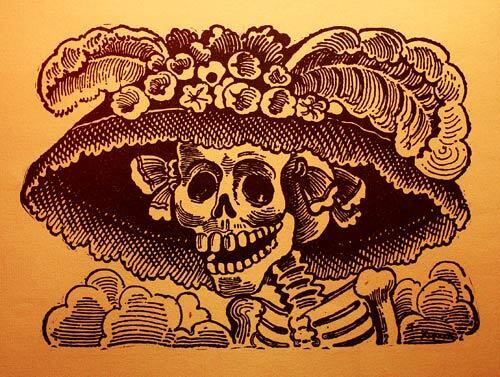

La Catrina is a satirical calavera (skull) by José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), a master engraver and native of Aguascalientes, which also has a museum devoted to his life and work. Indeed, the prosperous city of about 630,000 is known for its annual Festival of Skulls during Day of the Dead week. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

Advertisement

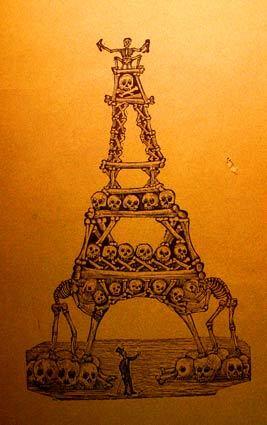

Putting a whimsical spin on the Parisian landmark is La Torre Eiffel by Manuel Manilla, also a Mexican artist of note. For that matter, every object in the museum was made by Mexican hands, says García, the institutions director general. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

“El Quijote” by Jose Guadalupe Posada (Mexico’s National Museum of Death in Aguascalientes, Mexico, August 9, 2007) (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

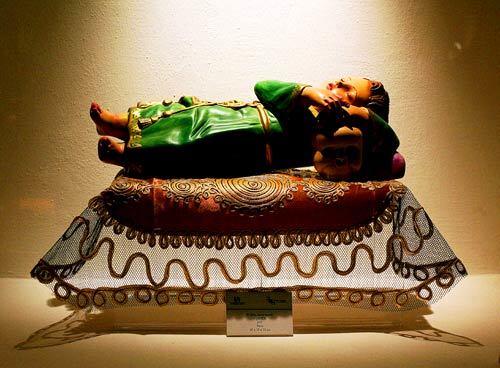

¡§El Nino de la Suerte¡¨ (The Child of Luck) projects serenity. Museum donor Bajonero was a student when he began acquiring death-themed objects, including objects that no longer are made or that exemplify a generational know-how that is dying out. ¡§When I realized I had an important collection with 1,500 objects, I thought, ¡¥What am I going to do with all this?¡¦|¡¨ he wondered. And thus the birth of a museum about death. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

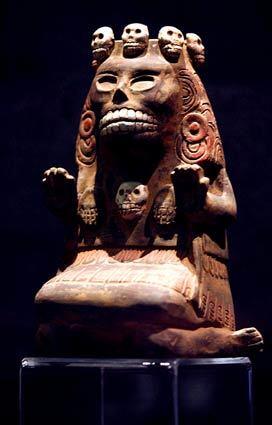

A sculpture of Cihuateotl. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

Advertisement

A funeral offering from the 7th century is one of the oldest pre-Columbian artifacts in the National Museum of Death. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

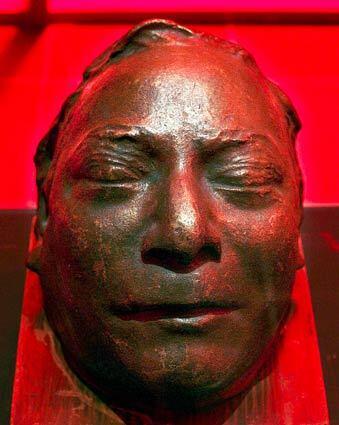

A mold taken of the face of Mexican 19th century reformist president Benito Juarez after his death on July 18, 1872. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

A pre-Columbian artifact draws the gaze of a young museum visitor. The museums holdings were assembled by Bajonero over 50 years. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

A family casually makes its way among pieces that include a skeleton. For the Mexican, [death] is very natural, as natural as to be born. Its not a tragedy, says Bajonero. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)

Advertisement

The courtyard of the former Carmelite convent that houses the museum, which is organized and operated by the Autonomous University of Aguascalientes. (Jennifer Szymaszek / For The Times)