Alcatraz: Getting rattled on ‘the Rock’

- Share via

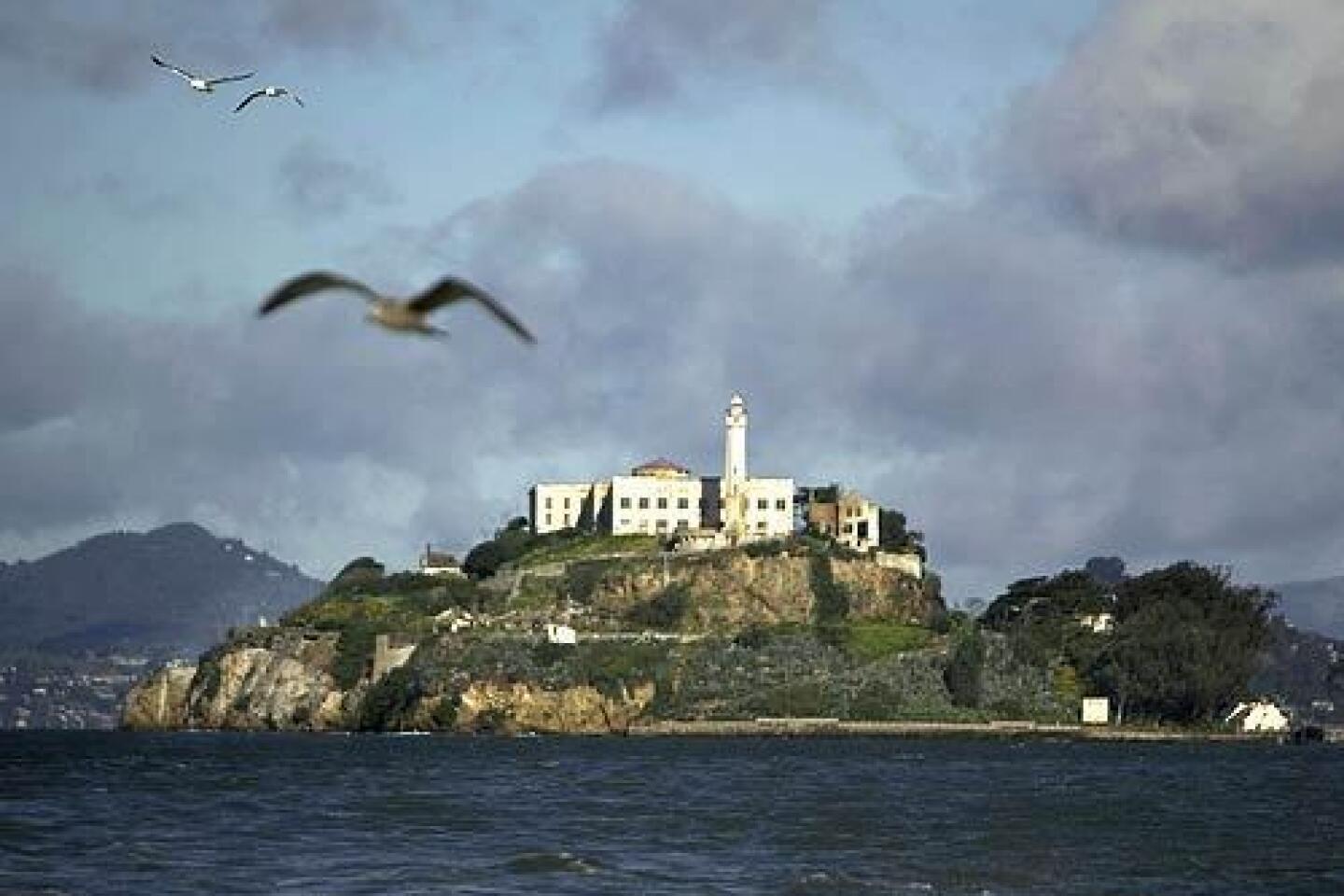

Alcatraz Island, Calif. — EACH day at sundown, when the last tour boat departs this desolate, wind-swept outpost, one lonesome soul is left behind. He’s the night watchman of Alcatraz.

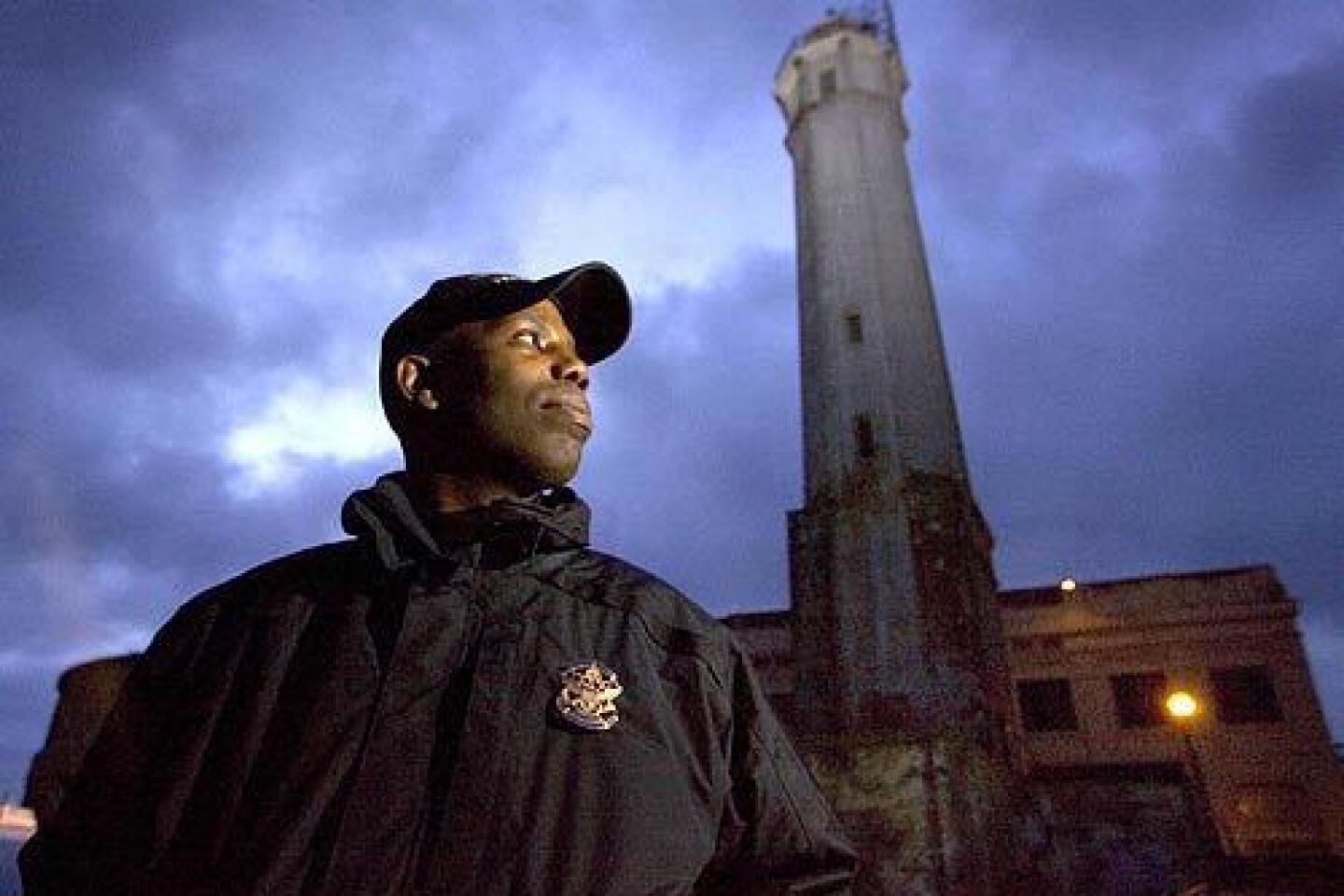

Guided by the beam of his flashlight, Gregory Johnson inches down the gloomy infirmary ward of this retired prison, once home to the nation’s most malicious killers and psychotic criminal malcontents.

“Hey, what’s that noise?” he asks, throwing the light against the half-open door of a solitary confinement cell. He pauses, shrugging off another unexplained Alcatraz phenomenon.

“Man,” he whispers, “I couldn’t imagine being out here at night without my gun.”

Until the first boat arrives after dawn, the U.S. park police officer spends the night battling both his nerves and imagination, patrolling the place once known as America’s Devil’s Island.

Over the years, Alcatraz was the dreaded last stop for 1,576 luckless hard-timers — murderers, mobsters, the nation’s most-wanted crooks — many of whom officials feared couldn’t be confined anywhere else.

Known as “the Rock,” the 12-acre penal island was notorious for its cramped cells and rigid discipline that at times demanded total silence. The prison also inflicted its own brand of emotional torture. At night, as the stories go, inmates could hear women’s laughter on the mainland 1 1/2 miles away.

Decades after the prison closed March 21, 1963, with inmate Frank Weatherman’s valediction, “Alcatraz was never no good for nobody,” all that remains is the lore of the desperate men once locked up here.

“I don’t believe in ghosts, per se,” says Johnson, 38, a no-nonsense law enforcement veteran. Still, holding a shackle of oversized keys, he cautiously makes his moonlit rounds across the island, some areas wanly illuminated by ancient light fixtures, others left eerily dark.

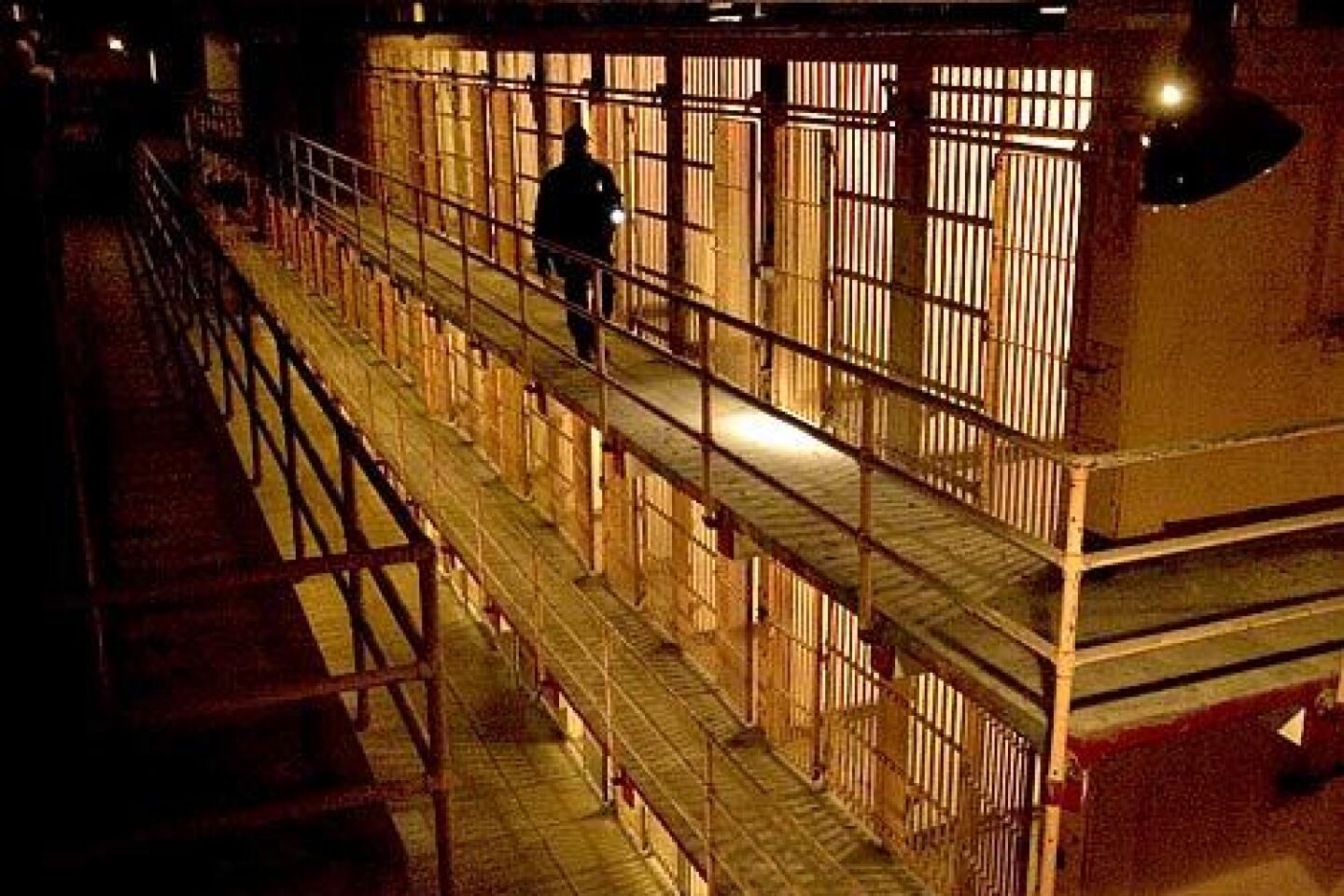

His footsteps echoing, he walks the old cellblocks that once housed notorious bank robber and gangster Arthur “Doc” Barker and kidnapper Alvin “Creepy Karpis” Karpavicz, a former Public Enemy No. 1.

He checks the crumbling medical ward where Robert Stroud, “the Birdman of Alcatraz,” spent 17 years. He peers into the deserted laundry room, now strewn with shattered glass, where Chicago mobster Alphonse “Scarface” Capone hustled among the industrial washers. He patrols the cramped office of hard-boiled wardens nicknamed Saltwater, Gypsy, Cowboy and Promising Paul.

Every now and then, the old prison plays tricks on his mind.

One night, as the buoy bells clanged and the foghorn moaned, he swore he heard clinking glasses, as if a toast were being made. He hears mice skitter on cellblock floors, and the wind howling outside often seems like crazy laughter.

“This is one creepy place after dark,” he said. “It can make the hair on the back of your neck stand up straight.”

For years, ferry company employees were assigned to the island’s night shift. Last fall, when the National Park Service, which runs Alcatraz, changed ferry services, park police took over until the new contractor begins work this month.

Officers watch both the ferry docks and federal facilities, mindful of pranksters on motorboats or protesters. After all, Native Americans fighting for civil rights once occupied Alcatraz for 19 months, starting in November 1969.

Johnson initially balked at the duty he shares with other officers. “I said, ‘You want me out there all by myself? Once you’re there, you can’t get off.’ ”

At first, he tried to tame Alcatraz by absorbing its history. He took the park service’s audio tour, walking alone among the cellblocks, guided by the recorded voices of former guards and inmates.

Then he took a different tack: reveling in his fear.

Inside Capone’s old cell — No. 200 on the second tier of B block — he watched horror movies on his laptop, flinching at each murder and bloodletting.

He soon questioned that decision.

“I like to be scared, but not that scared,” he said.

“I had to remind myself, ‘There’s no one out here but me. So just put that stuff out of your mind.’ ”

BETWEEN 1934 and 1963, the Civil War-era military fortress turned penitentiary provided many inmates with the hardest time they ever did, in part because San Francisco’s twinkling cityscape reminded them of the freedom they’d lost. Some found it too painful to even look at the skyline.

George DeVincenzi, a guard at Alcatraz from 1950 to 1957, said the proximity of the California culture drove many prisoners nearly insane. “Yachts circled the island, and men on the third tier of C and B blocks could see girls in bikinis drinking cocktails,” he said. “It was so near, and yet so far.”

The mind games got crueler. “After dark, it got colder and danker,” DeVincenzi said. “You could hear the bellow of the fog horns. It was a lonely, sometimes scary sound, even for the murderers among us.”

In all, eight people were killed by inmates at Alcatraz. One guard was murdered in an assault in the prison’s laundry room in the late 1930s, and two others died during an attempted breakout in 1946. Five inmates were killed in random attacks. Five other prisoners committed suicide.

DeVincenzi witnessed a killing on his first day as a guard. He’d been assigned to the prison’s barbershop. Easy duty, he figured. Early in his shift, as he was watching an inmate shave another with a straight razor, all hell broke loose.

“The barber’s name was Freddie Lee Thomas, and suddenly he takes his shears and starts stabbing the man in the chair,” DeVincenzi recalled. “He’s slashing his neck and arms, and I’m blowing my whistle. Within moments, the man is dead, lying in a pool of blood. I guess the two were lovers.

“Freddie hands me the bloody shears. Then he leans over the body and kisses the dead man on the forehead. “Goodbye,” he said. “I love you.”

Years after the prison shut its doors, the island’s sense of seclusion remains. Until the use of cellphones, night watchmen relied on a dated ship-to-shore phone to reach the mainland, making many feel marooned at sea.

Erik Novencido worked the island night shift for 10 years. The worst part was walking inside the electroshock therapy room. Once he took a picture at night to show friends. When he developed the film, he says, the snapshot showed a face in the room staring back at him.

He never figured out what it was.

“Sometimes I was just overwhelmed by fear,” he said. “The rangers told me stories about the things that happened here. And I’d say, ‘Keep that to yourself. I’ve got my sanity to keep.’ ”

Veteran park ranger Craig Glassner has been afraid even during the day. “Once on an isolated spot I heard this ‘Whooooo, whooooo,’ like someone blowing on a big Coke bottle,” he said.

“I thought, ‘Do I run?’ Then I saw it was the wind blowing across the stanchions of a fence. It really freaked me out.”

Mary McClure, who spent 12 years working nights on Alcatraz until last fall, preferred the isolation. She couldn’t wait for the last tourist to leave. “It was the standard fantasy of being alone on an island,” she said. “Well, maybe not Alcatraz.”

Even so, there were strange events. “Many times, at night in the cell house, I had the distinct sensation of being pinched on the butt,” said McClure, 52, a former paramedic. “It happened with great regularity. I have no explanation for it, and I don’t talk to people about it, because I know it makes me sound crazy.”

Former inmate John Banner spent four years here in the 1950s. He still recalls the squeal of the wind at night.

“Laying awake, listening to that wind, trying to hold on to what sanity I had left, I always thought of the brutality of that prison,” said the convicted bank robber, who lives in Arizona.

Now 83, Banner can’t imagine facing Alcatraz alone, at night. “I don’t believe in spooks,” he said, “but why on earth would a person want to do that?”

WHEN darkness comes, you don’t leave Alcatraz; you flee.

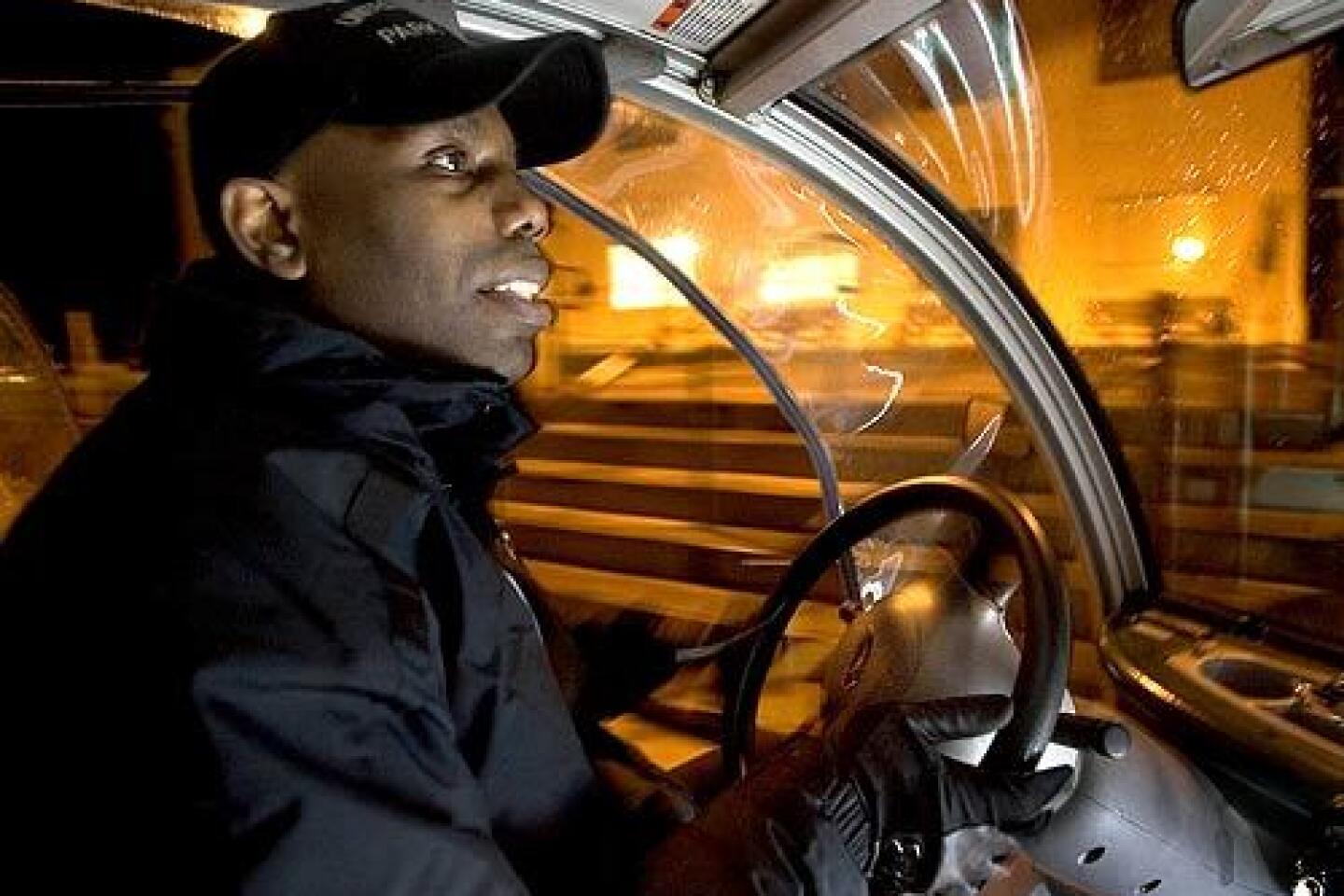

Amid a driving rain, a ranger hands Johnson the keys to the island — hurrying toward a ferry that soon whisks away the last of the day’s 5,000 visitors.

Johnson stands solitary amid the gathering seagulls. The big birds are now everywhere, lined up on walls, circling like vultures.

They make him uneasy.

“It’s like they’re watching me, to see if I’m going to crack,” he says, “like in that Alfred Hitchcock film, ‘The Birds.’ ”

He makes a sweep for any tourist stragglers and settles in for the long night.

Johnson’s father was a prison guard in upstate New York. He has the job in his blood. But Alcatraz is different.

The last rays of sun now gone, the island fortress becomes a grim, humorless place, the stuff of black-and-white 1950s crime photos. Johnson plays upbeat music on his iPod — Prince, Wham, Michael Jackson — to lighten the gloom.

He earns overtime pay for his 18-hour shifts (3 p.m. to 9 a.m.), but sometimes, in the dead of night, he says, “it seems like blood money.”

At 8 p.m., dressed in a black cap and windbreaker, his radio squawking with park police chatter, Johnson winds his way up a switchback as birds dive-bomb from ledges. In the rain, the cell house looms up ahead like a haunted castle.

He walks cellblock rows that inmates nicknamed Broadway, Sunset Alley and Seedy Street. He enters a solitary cell, its heavy iron door creaking. The tiny quarters remain perfectly black even after his eyes grow accustomed to the space.

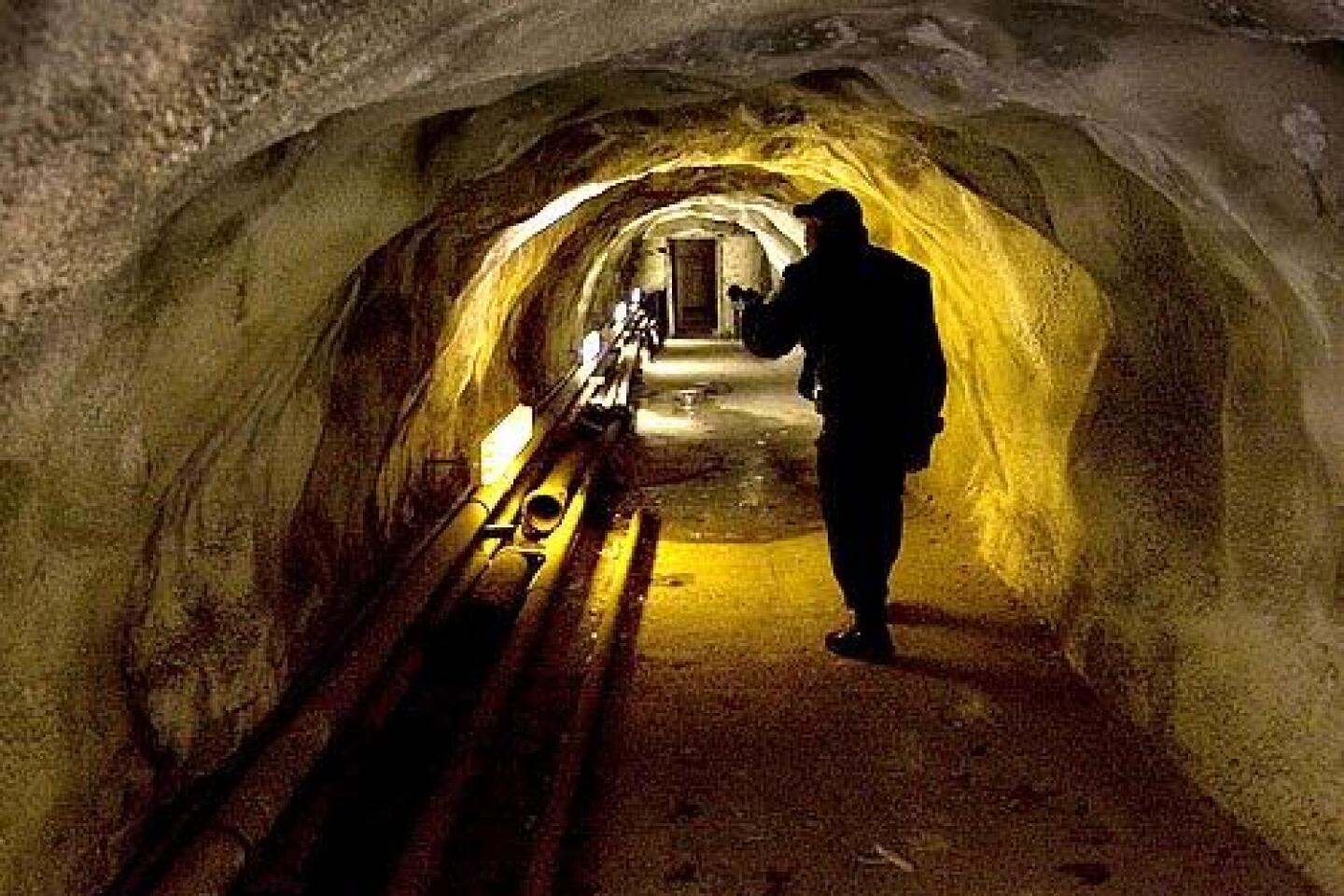

He stops at the cell of Frank Lee Morris, whose daring breakout was immortalized in the film “Escape from Alcatraz.” Morris and two others left inside their cells dummy heads fashioned out of soap and toilet paper — complete with hair from the barbershop. The idea was to fool guards while they left through holes chiseled in their cell walls.

Johnson looks at a model of one fake head left in the cell as a tourist display. He knows how the men felt: “Ten years here? I’d go crazy before that.”

By dawn, the night watchman is weary of the Rock. Passing the keys to a ranger, he makes his own escape from Alcatraz, the sun on his face.

john.glionna@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.